The term casting couch first appeared in Variety on Nov. 24, 1937, in a story poking fun at a Chicago Tribune reporter for misusing it because he wasn’t cool enough to already know what it meant. That Tribune reporter was writing about a new system at Chicago’s WBBM whereby only women were allowed to audition female radio talent—and if you wonder what might have prompted WBBM to ban male executives from the process, well, no one comes right out and tells, just as for decades no one came out and told the stories lots of industry insiders were whispering to each other about Harvey Weinstein.

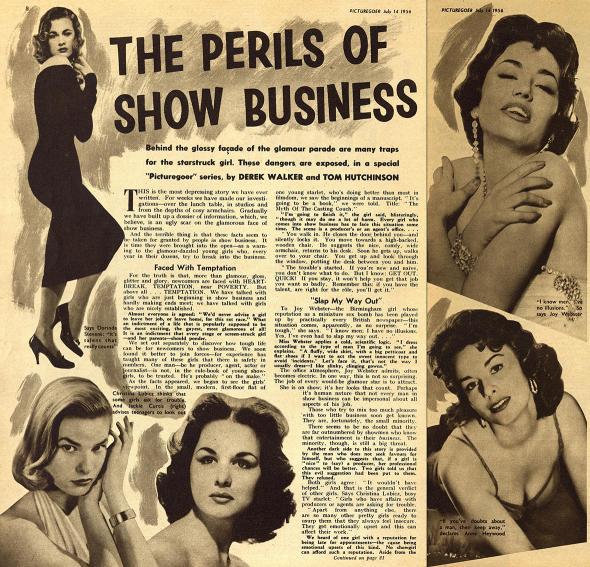

Now they are. But this isn’t the first time that we’ve all been shocked, shocked to find gambling in this particular casino. On July 14, 1956, Picturegoer, a British fan magazine, published the first chapter of an explosive four-part exposé about the casting couch that is simultaneously revelatory and depressing. It reveals that Weinstein’s playbook for allegedly abusing women would have been right at home in the 1950s. It also reveals, not for the first time or the last, the ways that reporters’ internalized biases and tendency to sensationalize can lead them to report a story in the least helpful way possible. And sadly, it reveals how little some things have changed: Between the lines of the article, women are trying desperately to sound an alarm, and no one is listening.

The series was called “The Perils of Show Business,” but it dealt with exactly one peril: men who promised actresses career advancement in exchange for sexual favors. Derek Walker and Tom Hutchinson shared the byline, because women would tell their stories to two men together but would not meet with a reporter alone. As the reporters explained, “experience has taught many of these girls that there is safety in numbers.” What they discovered was an industry in which abuse was commonplace and consequences were nonexistent, as their blunt introduction made clear:

This is the most depressing story we have ever written. For weeks we have made our investigations—over the lunch table, in studios, and from the depths of cozy armchairs. Gradually we have built up a dossier of information, which, we believe, is an ugly scar on the glamorous face of show business.

And the terrible thing is that these facts seem to be taken for granted by people in show business. It is time they were brought into the open …

Walker and Hutchinson’s first story in the series is filled with on-the-record accounts of horrifying episodes of sexual harassment, told by a variety of actresses who were coming forward to help other women avoid similar abuse. How unprepared was Picturegoer—by then pushing cheesecake photos to compete with theater-chain–owned publications—to publish this kind of hard-hitting reporting? Well, here’s how they laid out the story:

Picturegoer

There’s always some tension between the story a source wants to tell, the story a reporter wants to write, and the story a publication wants to sell, but rarely is it as obvious as it was here. Pulpy headings like “Faced With Temptation” and art that suggests literal flames of hell engulfing sexy photos of the women who spoke out are not, presumably, what actresses like Joy Webster, Dorinda Stevens, Anne Heywood, and Marigold Russell had in mind when they told their stories to Walker and Hutchinson. Walker and Hutchinson, in turn, probably didn’t anticipate the hypersexualized art design. And yet their stories are there, in print, with unnamed producers using tactics that sound awfully familiar:

A producer over here [in England] offered Dorinda Stevens a role.

Would she “dine” with the producer? Miss Stevens refused. Once, twice, three times the assistant rang. Miss Stevens went on refusing.

The assistant altered his tactics. Would Miss Stevens read over her lines at the producer’s flat? Only, was her reply, if other people were there. This was agreed. Miss Stevens went—and found herself alone with the insistent producer. She walked off and abandoned the offer.

As with their determination only to meet with reporters in pairs, most of the actresses quoted in the piece had to follow an elaborate system of rules to avoid harassment. Marigold Russell summed them up like this:

One: when you have to talk business, stick to offices—and office hours. Two: refer invitations and offers to your agent. Three: don’t give your home phone number, give your agent’s.

These rules were passed down from one actress to another, but the pervasiveness of sexual harassment and abuse was such that, as Anne Heywood explained, a zero-tolerance policy was the only way to survive: “Use your intuition. If you have any doubt in your mind about a man, keep away.”

Of course, the entire story is filtered through Walker and Hutchinson’s own biases and the unstated assumptions of the time: that it was the responsibility of actresses to avoid what the reporters repeatedly described as “temptation,” and that women who yielded to producers’ pressure were to blame for any career fallout that followed. (“No showgirl can afford such a reputation,” they sniffed.) And the follow-ups in the series would have done little to inspire other victims to step forward: Part Three was literally headlined “Don’t Always Blame The Men” and told stories of would-be actresses throwing themselves at producers.

No one would report a story about producers demanding sexual favors as a condition of employment today the way Walker and Hutchinson did in the 1950s, much less accompany it with cheesecake photos of the women who were speaking out. But when it came to Harvey Weinstein, for years, no one was able to report the story at all. Weinstein and his enablers allegedly saw to that personally, whether through restrictive non-disclosure agreements, legal threats, or even the strategic deployment of an unwitting Matt Damon. It’s a playbook at least as old as Weinstein’s alleged business-meeting-that-turns-personal M.O., hearkening back to the days MGM managed to keep its name out of initial reports of the Patricia Douglas scandal. Despite any number of talented reporters chasing the Weinstein story for years—David Carr, Sharon Waxman, Ken Auletta, and Rebecca Traister all took a swing at it—until Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey broke the story at the New York Times, and Ronan Farrow followed up at the New Yorker, no one was able to nail down the details in the face of what Farrow called “a vast machine set up to silence these women.”

If there was any fallout from Picturegoer series, it didn’t make the papers. Nobody got fired, nobody was disgraced, nobody followed up. Nearly 20 years later, on May 21, 1975—so around the time producer Sam Spiegel was allegedly trying to force himself on Theresa Russell, but a few years before Roman Polanski was arrested for sexually assaulting a 13-year-old—Variety, reporting on a new committee the Screen Actors Guild was establishing to investigate what were euphemistically called “morality complaints,” asked, “ ‘Casting Couch’: Fiction or Fact?” Once again, the casting couch had become the stuff of myth, legend, and blurry photos of Golden Age studio moguls, despite a story on the very same page of the paper about a producer who had pled guilty to second-degree rape after an incident involving a 12-year-old at an audition. (You can find both the Variety and Picturegoer articles on ProQuest, but a subscription is required.)

Things have changed since the 1950s: Weinstein’s rapid downfall counts for something, even if we just elected Donald Trump president, and much of the reporting on Weinstein’s alleged wrongdoing has been free of the kind of sexism and shaming that often accompanied such stories 60, 40, or even six years ago. But building an industry and culture in which powerful men don’t feel women are theirs to threaten, cajole, intimidate, and harass will require us to skip the cultural amnesia this cycle.