In a climactic scene in Kurdish novelist Bakhtiyar Ali’s I Stared at the Night of the City, the hero, a poet known as Ghazalnus, argues with a powerful and shadowy figure referred to as the Baron of the Imagination. The Baron is trying to recruit Ghazalnus on behalf of the political authorities to help build a planned “city of the imagination” in Kurdistan. The baron sees poetry as a tool of political progress: “Politicians first speak about freedom and then poets come and sing its songs.”

But Ghazalnus, whose nickname refers to a poetic form usually used to express love or mystical themes, makes the case for artistic detachment. In an inversion of the old Stalinist slogan that the role of artists is to be “engineers of the human soul,” he argues that “poets are the architects of their own exile” and that “it is the poet’s job to reside in exile and look at life from there.” The role of the poet is to observe society from the outside rather than participating in it directly.

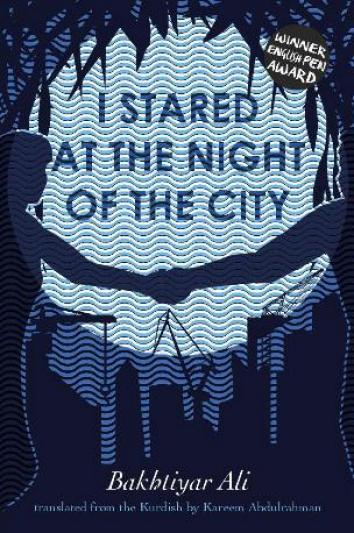

Ironically, a novel that celebrates artists’ inherent right to detach themselves from politics and the whims of politicians will inevitably read as a political project. I Stared at the Night of the City, first published in the Kurdish region of Iraq in 2008, is believed to be the first novel ever translated from Kurdish to English. Its release, scheduled for early 2017, comes at a time when Iraqi Kurds are closer than ever to becoming a fully recognized independent country, a goal that’s been pursued for more than a century of marginalization, international betrayal, internal divisions, and genocide.*

In a recent Skype interview, the book’s translator Kareem Abdulrahman told me he was unbothered at the book being deployed for political purposes. “All Kurds are political beings,” he said. “You can’t be apolitical when you have that sort of history.”

He also saw it as a missed opportunity that Kurdish literature has not been more widely promoted. “As a nation, but especially our public and political institutions and organizations, we don’t understand the importance of culture in both putting the Kurds on the cultural map of the world and in supporting the Kurdish cause,” he said.

Abdulrahman, a London-based journalist, not a literary translator, got involved in I Stared at the Night of the City in a roundabout way. In 2008, he wrote an article about the novel’s success in Kurdistan for the Times Literary Supplement; soon after, he was approached by an agent. (Update: Abdulrahman has since acquired formal training as a literary translator.) *

He says the book, originally titled Ghazalnus and the Gardens of Imagination, is a good introduction for international readers, as it “has one leg deeply planted in politics and modern Kurdish history but one also in the wider role of literature itself and more universal themes.”

The novel tells the story of a group of artists and dreamers known as the “imaginative creatures,” who set out to solve a murder mystery in an unnamed Kurdish city controlled by powerful and malevolent “barons.” (The Baron of Imagination got a more impressive title than the Baron of Porcelain and the Baron of Courgettes, who also play key roles.) The “creatures” include a hit man, a mystically powerful weaver of carpets, a “real Magellan” returned from travels abroad and an “imaginary Magellan” who leads a group of blind children on journeys of the mind. Real events in Kurdish history, such as Saddam Hussein’s extermination campaigns and the internal civil war that divided the region in the 1990s are referred to only obliquely. The line between fantasy and reality is especially porous, and flights into poetic mysticism are sometimes broken up by jarring references to politics, history, or pop culture. (The filmography of Johnny Depp comes up more than you might expect.)

The theme of imagination and its uses is certainly a pertinent one for a people for whom nationhood has been a dream rather than a reality. (It’s seems unlikely Ali had it in mind, but one classic treatise on nationalism, which strongly emphasizes the role of literary culture in nation-building, is called “imagined communities.”)

With roughly 25 million Kurds living in their home region—split between Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran—and large diaspora populations in Europe and North America, not to mention their prominent role in international crises from the Gulf War, to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, to the fight against ISIS, it’s somewhat shocking that Kurdish literature is almost wholly unknown in the West.*

The fact that there’s no independent Kurdish state to promote this work may be one reason. “Although there’s a large Kurdish community in the West, we haven’t managed to create the right institutions and tools to be able to promote Kurdish culture and literature,” says Abdulrahman. Kurdish language and culture was also suppressed for many years in the countries where they live. The language itself is divided into several dialects. The book was written in Sorani, spoken predominantly in Iraq and Iran, but most Kurds in Syria and Turkey speak another dialect, Kurmanji, or a number of smaller dialects.

Abdulrahman also notes that, “Kurdish fiction in general is quite new. Only in the past 60–70 years have we started to produce stories and novels even more recently than that.” Poetry on the other hand, has a much older and richer history. “Poetry is the most dominant form throughout Kurdish history, and I think Bakhtiyar deliberately chose a poet to be the symbol and representative of intellectuals, because all the other traditions are very new,” says Abulrahman.

Being the first to translate a novel between two languages presents some unique difficulties, including a lack of reliable Kurdish-to-English dictionaries. Abdulrahman recalls the word atamin, which means “embroidered muslin” and turned out to be borrowed from French via Arabic, giving him particular headaches.

He also didn’t pick an easy book to start with. I Stared at the Night of the City is a 542-page behemoth featuring multiple narrators, dozens of characters, a nonlinear chronology, and large sections written as poetry.

Abdulrahman hopes this will be the first of many Kurdish novels to make their way into the English-speaking world, though reflecting on the project, he concedes, “You need a huge amount of time and stamina just to get it to the finishing line.”

*Correction, Jan. 3, 2017: This piece originally stated that the book is available in the U.S. only as an e-book. It is available in both the U.S. and Britain in both print and e-formats. It also misstated that Abulrahman was approached to translate the book after writing an article for the BBC. It was for the Times Literary Supplement. It also put the number of Kurds living in the Middle East at roughly 20 million. Most estimates suggest there are at least 25 million.