Straight Outta Compton, the NWA biopic, has won accolades from critics and won the weekend box office, too. The film offers a slick, captivating account of the group’s rise in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and for the most part the period details are handled expertly, from the clips of Peter Jennings and Tom Brokaw newscasts to the 1960s-era Chevys tricked out with 1980s-era suspension packages. The casting director even found an O’Shea Jackson to play O’Shea Jackson. But keen-eyed fans have noticed that when it came to wardrobe, the filmmakers took some surprising shortcuts, undermining the authenticity of a film about a group that helped establish street authenticity as a sine qua non of rap stardom.

As various observers have noted, the film’s very first sequence contains a glaring breach of the sports-time continuum. That scene, in which Eric Wright—later Eazy E—engages in a tense standoff with a house full of irritable drug dealers, is set, we’re told, in 1986. And yet Wright wears a Chicago White Sox hat with the team’s “Sox” logo written out in a distinctive gothic script, stacked vertically. That logo didn’t yet exist in 1986; as USA Today’s For the Win blog noted, and the White Sox have now confirmed in a mildly comic official statement, it wasn’t introduced until 1990, and wasn’t adopted by the team until 1991. In 1986, the team was still wearing a cheerful red, white, and blue logo better suited to an Independence Day parade than a visit to a stash house. Chicago’s own WGN has helpfully photoshopped the correct Sox hat onto Eazy’s Jhuri curls to prove the point.

But jumping the gun on the White Sox logo isn’t the only mistake the movie makes—it’s not even the only mistake it makes on that hat. The hat also features the Major League Baseball logo, a detail that renders it doubly anachronistic. The New Era Cap Company, the official supplier of MLB’s on-field fitted hats, had not yet begun placing the MLB logo on the back of its hats in 1986. Aggie Szajda, senior PR manager at New Era, told me that the company began that practice in 1993.

This may seem like an absurd exercise in nitpicking, and it is. “I think it’s fucking hilarious that people are making a big deal about that,” the film’s costume designer, Kelli Jones, told Uproxx in an interview published on Wednesday. But NWA had a distinctive look, one that was not incidental to its appeal. Their music offered a bracing glimpse of life in the gang-dominated enclaves of South Central Los Angeles, where subtle sartorial cues could suggest allegiances as much as an aesthetic. Indeed, though neither Dre nor Cube were bangers themselves, NWA presented itself as a gang as well as a group, and this presentation was very much part of the vicarious thrill of following them: “This is a gang, and I’m in it,” Cube raps on “Gangsta Gangsta,” “my man Dre will fuck you up in a minute.” Other rappers had costumes—Slick Rick’s signature Kangol and eye patch, for example. NWA had something closer to colors.

Eager to establish the West Coast as a rap hub worthy of a rivalry with the East Coast, where the art was born, the group favored the apparel of the sports teams of their native Los Angeles. They had a particular fondness for the gloomy black-and-gray color scheme shared by the NFL’s Raiders and the NHL’s Kings, though a more cheerful Dodgers jersey or fitted hat would also do just fine for a night out at Eve’s After Dark.

Strangely, even when it comes to the Los Angeles apparel, the film errs. Both Dre and Ice Cube wear L.A. Dodgers hats in which the team’s royal blue has been replaced by a midnight black and the stitching of the L.A. logo, which is usually white, is rendered in black as well. The hats show up in scenes set in the late 1980s and early 1990s: See, for example, this snippet from the film’s official trailer, in which Ice Cube is wearing the hat during the studio session that will produce the 1987 hit “Boyz-n-the-Hood,” or this one, from the red-band trailer, in which Dre drives through Los Angeles during the 1992 riots. New Era helped popularize these blacked-out riffs on teams’ on-field caps, but Szadja confirmed my memory that the style, known at the company as Black on Black or ONYX, didn’t appear until 2003.

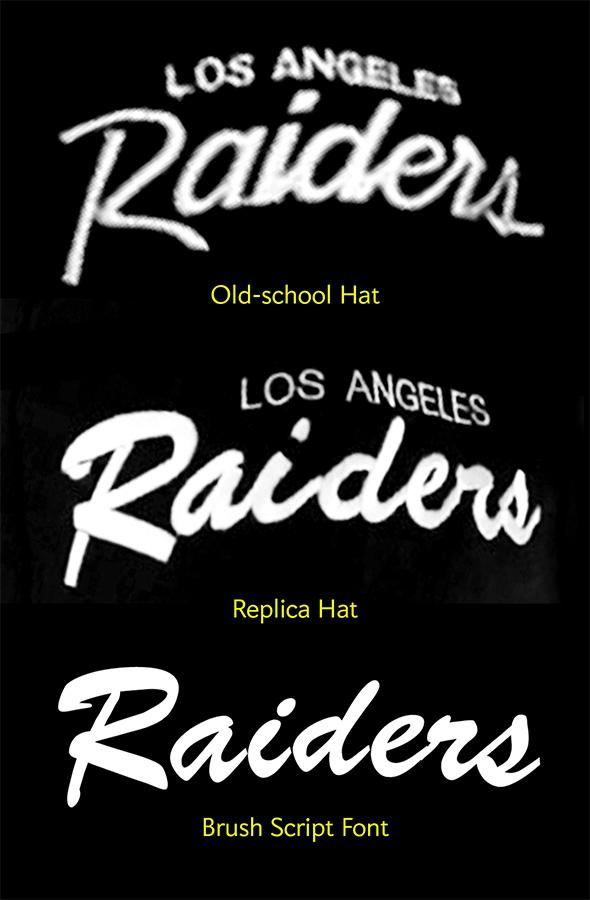

More subtle, though arguably more egregious, is the wardrobe department’s failure to nail the Los Angeles Raiders caps that NWA made iconic. The discrepancy is subtle, but as commenter Charles N. on the indispensible Uni-Watch blog noticed, the filmmakers seem to have commissioned replicas of the period hats, but not taken pains to get them right. Jones acknowledges in the Uproxx interview that she recreated the Raiders gear—in an effort, she says, to accurately render the period font. But a close look at the Raiders hats in the film reveal that the team name has been scrawled in a generic “Brush Script” font, which approximates but does not fully capture the more idiosyncratic writing on the hats popular at the time. Note, below, the difference between the R, which in the original wanders with delightful aimlessness toward the rest of the word, and in the replica takes on more of a faux-graffito feel. Also note the A, which is more standoffish in the original than in the replica:

Photo illustration by Slate.

If you’re going to the trouble to make replica hats, it doesn’t seem like it would be much harder to get the script just right. Alternatively, Jones could have tracked down some deadstock hats from the period, which occasionally still trade on Ebay, at prices too dear for most consumers though not for costumers on major motion pictures.

Viewers today have been conditioned by the obsessive likes of Mad Men’s Matthew Weiner into expecting period accuracy that borders on the fetishistic, and perhaps that’s not necessarily to the good. Capturing every last nuance of hardware and hem line can become an end in itself, and not one that’s able to rescue a bad script or poor acting. Straight Outta Compton more than gets by on the strength of its lead performances and the appeal of the unlikely success story at its heart. But for rap fans of a certain age and cast of mind, who might still have a Sports Specialties cap or Starter jacket in their old closet at their mom’s house, the movie loses a not-negligible amount of cred. When an extra at Eazy E’s Wet N’ Wild Party boogies into the shot wearing a Kareem Abdul-Jabbar jersey with a prominent Adidas logo on the breast, it distracts. Adidas didn’t secure the NBA contract until the early aughts, a decade after Eazy inflated his last beach ball. The die-hard fan’s attention should be on the bacchanalian excess of the fete—as rap fans know, pool pride goes before a fall. Instead, he finds himself shaking his head, wondering how a film made by and about L.A. royalty didn’t manage to get its hands on an authentic Kareem and instead settled for a replica anyone with $109.95 can get at NBAstore.com.