This weekend, Saturday Night Live kicks off its 40th season. To mark the occasion we asked writers from the show to tell us about performers they loved writing for. Below, Jack Handey remembers Phil Hartman, who would have turned 66 today.

One day I was hanging out with some SNL writers and cast members in the 17th-floor conference room. It was shortly after the writers had won an Emmy Award for the 1988-89 season. Phil Hartman, who had been a writer as well as a cast member for the winning season, marched in with an 8-by-10 photo of himself. It showed him cradling his Emmy Award in one arm and his newborn child in the other. He tossed the photo down in front of his good friend Jon Lovitz and said, “Check it out, Lovitz—two things you’ll never have.”

It was one of the few times I ever saw Phil clown around at the office. His demeanor was usually that of the reserved, self-contained Everyman. Not cold, but polite and pensive. He usually saved his comic brilliance for Studio 8H, where he was unequalled.

Phil Hartman was perhaps the best cast member, ever, of Saturday Night Live. I loved writing for him. So did the other writers. Phil was rarely “light in the show,” as the saying went.

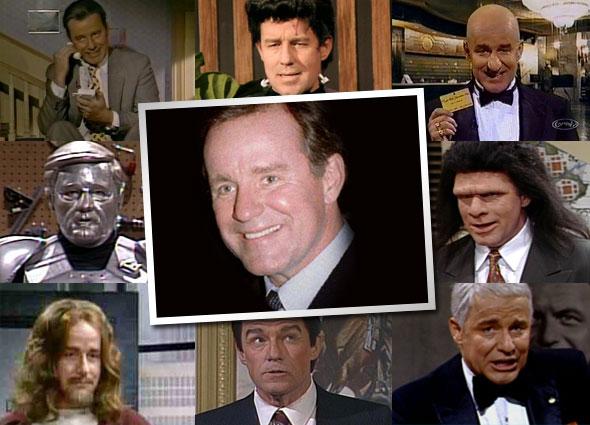

Roles I gave him, from an unfrozen caveman lawyer to a giant businessman to a frustrated robot, Phil made shine. He was especially good at being the patient, authoritative voice of reason, gently explaining to an idiot why he was an idiot, and why he had to stop being an idiot.

He could do any accent. He could play menacing or frightened.

He could basically do it all. You’d hand him the ball and he’d punch it over the goal line. If he couldn’t, the ball you handed him was probably slippery or flat.

Phil was cool under fire. I could go to him in the few minutes between dress and air, usually in the makeup room where they were applying a silly wig or prosthetic I had made him wear, and tell him that I had cut a page out of the script, that now he’d be saying this instead of that, that the chair would now break when he sat down on it, etc. He would calmly look over the changes and absorb them. I think he enjoyed the pressure.

In front of the live camera and live audience, he was fearless. He would stick with a piece even if it was dying, never rushing for the door or bailing out on it. And never breaking up.

Away from the show, Phil and I didn’t pal around. We were two professionals who respected each other, and that was enough. One night, at the after-show party, we spent the whole time gabbing and getting drunk. I have no idea what we talked about, but I’m sure it was quite profound.

Ironically, it may have been his incredible versatility that hurt Phil in movies. He wasn’t easy to peg. He wasn’t the crazy wise-ass guy, or the bumbling, clumsy guy. He was too talented to be pigeonholed.

But that’s what made him so great for a writer like me. I didn’t have to build a sketch around his comic persona. I could just write a little play and cast him in it.

Several times since Phil’s death, I’ve had the same dream about him: I am back in the studio, working on Saturday Night Live, and Phil is there! “Phil,” I say, “I thought you were dead!” It turns out that it was a mistake that Phil was dead, or that now he’s some type of reanimated zombie. All I know is I am very happy to see him again.