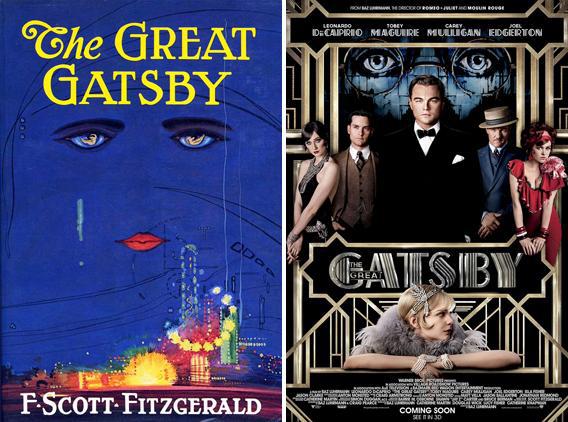

Ever since Baz Luhrmann announced that he was adapting F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby—and especially after he revealed that he’d be doing it in 3-D—much digital ink has been spilled about the hideous sacrilege that was sure to follow. Nevermind that Luhrmann’s previous adaptation, William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, was quite true to both the language and the spirit of that legendary play; Gatsby, as David Denby puts it in The New Yorker this week, is “too intricate, too subtle, too tender for the movies,” and especially for such an unsubtle filmmaker as Luhrmann.

So the argument goes, anyway. In fact, Fitzgerald’s novel, while great, is not, for the most part, terribly subtle. And though it has moments of real tenderness, it also has melodrama, murder, adultery, and, of course, wild parties. In any case, we can put aside, for the moment, the larger question of whether Luhrmann captured the spirit of Gatsby, which is very much open for debate. There’s a simpler question to address first: How faithful was the filmmaker to the letter of Fitzgerald’s book?

Below is a breakdown of the ways in which the new film departs from the classic novel.

The Frame Story

Luhrmann’s chief departure from the novel arrives right at the beginning, with a frame story in which the narrator Nick Carraway (Tobey Maguire), some time after that summer spent with Gatsby & co., has checked into a sanitarium, diagnosed by a doctor of some sort as “morbidly alcoholic.” Fitzgerald’s Nick does refer to Gatsby as “the man who gives his name to this book” (emphasis mine), so the idea that The Great Gatsby is a text written by Nick is not entirely original with Luhrmann—though the filmmaker takes this much further than Fitzgerald, showing Nick writing by hand, then typing, and finally compiling his finished manuscript. He even titles it, first just Gatsby, then adding, by hand, “The Great,” in a concluding flourish. (Fitzgerald himself went through many more potential titles.) As for that morbid alcoholism, Nick claims in the novel that he’s “been drunk just twice in my life,” but the movie slyly implies that he’s in denial, by showing him cross out “once” for “twice,” and then, in the frame story, suggesting that it was far more than that, really.

Jordan and Nick

The plot of the film is pretty much entirely faithful to the novel, but Luhrmann and his co-screenwriter Craig Pearce do cut out one of the side stories: the affair between Nick and Jordan Baker, the friend of Daisy’s from Louisville who is a well-known golfer. Daisy promises to set them up, to push them “accidentally in linen closets and … out to sea in a boat,” a line the screenplay keeps—but then, in the film, the matter is dropped. Luhrmann’s Nick says he found Jordan “frightening” at first, a word Carraway doesn’t apply to her in the novel—and later at Gatsby’s we see Jordan whisked away from Nick by a male companion, which doesn’t happen in the book. In the novel, they become a couple and break up near the end of the summer.

The Apartment Party

The film, like the novel, is a series of set pieces, including an impromptu party that Tom throws in a Manhattan apartment he keeps for his mistress, Myrtle Wilson, wife of a Queens mechanic. Nick accompanies them, and the film shows Nick sitting quietly in the apartment’s living room while the adulterous couple have loud sex in the bedroom. Fitzgerald doesn’t spell out anything so explicit—but something like that is implied: Tom and Myrtle disappear and reappear before the other guests arrive; Nick reads a book and waits. Luhrmann also shows Myrtle’s sister Catherine giving Nick a pill that she says she got from a doctor in Queens; that’s not in the novel at all. Luhrmann’s Nick wakes up at home, half-dressed, unsure how he got there, while Fitzgerald’s narrator comes to in an apartment downstairs from Tom and Myrtle’s place, owned by one of their friends (and party-guests); he then goes to Penn Station to take the 4 o’clock train home.

Lunch With Wolfsheim

In the book, Gatsby takes Nick to lunch at a “well-fanned 42nd Street cellar,” where he introduces his new friend to Meyer Wolfsheim, a Jewish gangster. In the movie, Gatsby and Nick go to a barber shop with a hidden entrance to a speakeasy, and once inside they see not only Wolfsheim but also the police commissioner—who, in the book as in the film, Gatsby was “able to do … a favor once.” They also see there (if I understood things correctly) Nick’s boss, whom I believe Luhrmann has turned into Tom’s friend Walter Chase. (In the novel, those are two different people, neither of whom we ever actually meet.) The speakeasy features entertainment from a bevy of Josephine Baker-like dancers, who are not mentioned in the book.

Race

At least one reviewer—David Denby again—has protested Luhmann’s decision to cast an Indian actor, Amitabh Bachchan, as Wolfsheim, a character based on notorious Jewish gangster Arnold Rothstein. But faithfulness in this case probably would have meant anti-Semitism, since it is very hard to defend Fitzgerald’s characterization of the “small, flat-nosed Jew” with a “large head” and “two fine growths of hair which luxuriated in either nostril.” Casting Bachchan preserves the character’s otherness while complicating the rather gruesome stereotype Fitzgerald employed. Luhrmann appears to have given some thought to this, given that he faithfully keeps key passages from the novel about race: Tom’s trumpeting of a racist book called Rise of the Colored Empires (which had a real-world inspiration), Nick’s glimpse of apparently wealthy black men and women being driven into Manhattan by a white chauffeur, and Tom’s later diatribe about “intermarriage between black and white.”

The Finnish Woman and Ella Kaye

Did you know that Nick Carraway had a maid? This is easy to forget, since Nick seems generally financially a bit strapped, certainly in comparison to his rich neighbors. But in the novel he employs “a Finnish woman who made my bed and cooked breakfast and muttered Finnish wisdom to herself over the electric stove.” She makes a few appearances in the book but is understandably cut from the movie. So is Ella Kaye, the seemingly conniving woman who manages to snag the inheritance of Dan Cody, the rich, drunken yachtsman who first prompts Gatsby on his road to wealth and artifice. In the movie, Cody’s wealth goes to his family.

Gatsby’s Death and Funeral

Near the end of the book, Gatsby is murdered by George Wilson, the mechanic husband of Tom’s mistress, who has gotten it into his head that Gatsby killed her—and that, what’s more, he might have been the one she was sleeping with on the side. Fitzgerald doesn’t depict the murder: The book says that Gatsby grabbed a “pneumatic mattress” (i.e., a floater) and headed to his pool, then Gatsby’s chauffeur hears gun shots. Luhrmann ditches the pneumatic mattress and adds his own dramatic flourish. In both book and movie, Gatsby is waiting for a phone call from Daisy, but in the film, Nick calls, and Gatsby gets out of the pool when he hears the phone ring. He’s then shot, and he dies believing that Daisy was going to ditch Tom and go way with him. None of that happens in the book.

Gatsby is, in both versions, lonely in death, but the film is even crueler to him in this regard, dropping the last-minute appearance of his father and the unexpected arrival at the funeral of a man who Nick previously met in Gatsby’s study. This is the same man who famously points out that Gatsby has real books, but hasn’t cut the pages. We meet him in the movie in that study, but he makes no mention of the books, and his subsequent appearance is dropped entirely.

Read more in Slate about The Great Gatsby.

Previously

How True Is Pain & Gain?

How Accurate Is Lincoln?

How Accurate Is Argo?

Who Are the People in Zero Dark Thirty?

How Much Scientology Made It into The Master?