Atlas Obscura on Slate is a blog about the world’s hidden wonders. Like us on Facebook, Tumblr, or follow us on Twitter.

“The meals were the bright beacons in those cold and stormy days. The glow of warmth and comfort produced by the food and drink made optimists of us all.”

So wrote Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton of his 1914-1917 Endurance Expedition, a disaster-riddled attempt to make the first land-crossing of the continent. During a horrendous journey in which his ship sank after being crushed by ice, forcing him and his 28 men to camp for months in the snow, food provided one of the few sources of respite from the bleak surroundings. See Shackleton’s ode to salty, waterlogged crackers:

“A few boxes of army biscuits soaked with sea-water were distributed at one meal. They were in such a state that they would not have been looked at a second time under ordinary circumstances, but to us on a floating lump of ice, over three hundred miles from land, and that quite hypothetical, and with the unplumbed sea beneath us, they were luxuries indeed.”

For explorers and researchers enduring the dark, frosty monotony of an Antarctic winter, food provides an exciting source of variety. But the continent’s remoteness, limited accessibility, and conservation laws place heavy restrictions on what its visitors can eat.

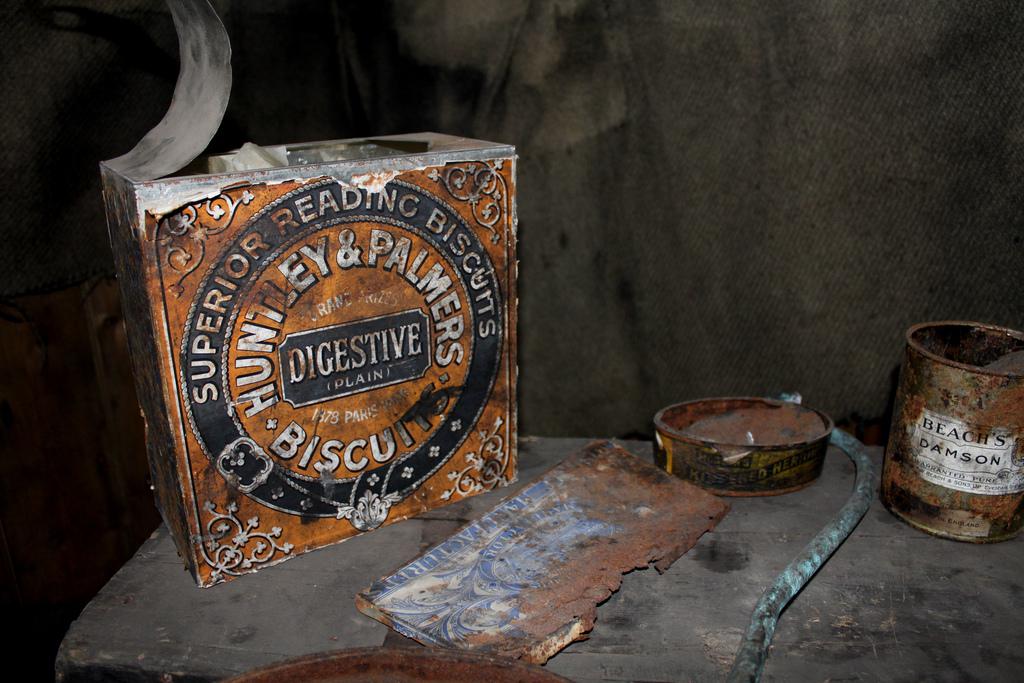

A look at the packing list for Ernest Shackleton’s 1907-1909 Nimrod Expedition offers a fascinating insight into on-ice dining during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Among the edible items, intended to sustain 15 men for up to two years, were 1600 pounds of “finest York hams,” 1260 pounds of sardines, 1470 pounds of tinned bacon, and 25 cases of whisky. The 408 pounds of ox tongues were supplemented with another 384 pounds of sheep tongues and 144 pounds of pork tongues, presumably for the sake of variety. Then there was the booze: whisky—25 cases of it—was the tipple of choice, with a bit of brandy (six cases), Champagne (six cases), and port (three cases) thrown into the mix.

Of course, back then, there were no rules. Those were the pioneer days of Antarctica, decades before the Antarctic Treaty forbade such acts as bludgeoning seals and penguins to death and stirring their blubber into porridge. (Both Shackleton and his fellow Heroic Age explorer Robert Falcon Scott did just that to survive during their harrowing expeditions.)

These days there are strict laws governing food importation, waste management, and environmental conservation. According to the treaty, nothing orignating from the continent can be eaten, which means no fishing, no foraging, and no feasting on seals. At McMurdo, the U.S. station where the majority of Antarctic researchers stay, delivery of dried and frozen food takes place just once a year, usually in January. During summer, planes deliver fresh produce around once a week.

In winter, however, things are dramatically different. The population of McMurdo shrinks from around 1000 to 150 people, all of whom must pass a stringent psych evaluation. It’s dark outside 24 hours a day. With flights to and from research bases ceasing for up to 10 months, researchers have to huddle up and learn to love non-perishables. Fortunately, there is still the occasional opportunity to eat fresh veggies courtesy of hydroponics: greenhouse gardens on the research bases provide lettuce, spinach, cucumbers, tomatoes, and herbs.

Twenty nations have research stations on the continent, and a few cultural differences are evident in each one’s approach to food and drink. According to the official rations list, each person at Australia’s Davis Station is allocated more than a pound of Vegemite per year. Vernadsky, now a Ukrainian research base, was established by the British in 1947—when the Ukraine took over in 1996 they changed all the decor at the station’s bar, made three-dollar vodka the signature drink, and established a new policy: free drinks for women willing to donate their underwear.

The provision of alcohol—how much, what kind, and whether to charge for it—has also been the subject of changing policies, but on a governmental level. Nowhere is this more evident than on an Australian Antarctic Division “Classroom Antarctica” website, aimed at children in grades five to eight: “Until 1998, the Commonwealth Government supplied generous quantities of alcoholic beverages to expeditioners free of charge. After visits to Antarctic stations by several politicians, the practice has now ceased.” (Researchers may drink home brew or purchase drinks at the bar, but any alcohol they bring from home is stored in a locked cupboard referred to as Fort Knox. It is accessible on a weekly basis.)

Food on base—where chefs prepare three meals a day, plus a midnight “midrat” ration—is different than food in the field. Researchers tasked with trekking through the snow for long periods are issued high-calorie rations designed to sustain them during hard work in polar conditions. That means a whole lot of chocolate bars. There is also pemmican, a squishy, compressed mush of protein and fat that can be eaten quickly—it’s in your stomach before you have a chance to reflect on how it tastes. (It will never be as bad as the pemmican eaten by Shackleton—his version contained the remains of his ponies and sled dogs.)

If all this talk of polar food has whetted your appetite for Antarctica, you can always apply to work in food service at McMurdo. Applications are currently open for sous chef, production cook, and baker positions for the 2015 winter season.

Visit Atlas Obscura for lots more on the wonders of Antarctica, including Trinity Church, the Port Lockroy Post Office, and the shrine-filled South Pole ice tunnels.