Last week, an astonishing blog post by a man named James Pinkstone circulated on social media. In it, Pinkstone claimed that he had lost 20 years’ worth of music files as a result of signing up for Apple Music; as he explained it, the service had hoovered up the collection of MP3 and WAV files he had been keeping in his iTunes library and replaced them with streaming versions that lived in an Apple-owned cloud. The original files, as Pinkstone understood it, had been deleted off his computer in the process. To his surprise, when he called Apple Support to find out what happened and how to fix it, he was told that this was exactly how Apple Music—the company’s year-old streaming service—was supposed to work.

These were disturbing allegations—especially if, like me, you had recently signed up for Apple Music for the first time so you could listen to the new Drake album as early as possible. It was particularly worrisome that a lot of the songs Apple Music had allegedly removed from Pinkstone’s hard drive weren’t properly replaced. For example, instead of a rare, early version of a Fountains of Wayne song that Pinkstone had at some point downloaded or ripped to his computer as an MP3, Apple had plugged in a less distinctive, more widely available version of the song.

Hold up, I thought to myself: Did this mean that anyone who downloaded the early, leaked version of Drake’s “Controlla,” which featured a fun guest appearance by Jamaican dancehall artist Popcaan, was going to wake up one morning and find that Apple Music had switched it out for the official, Popcaan-less album version?

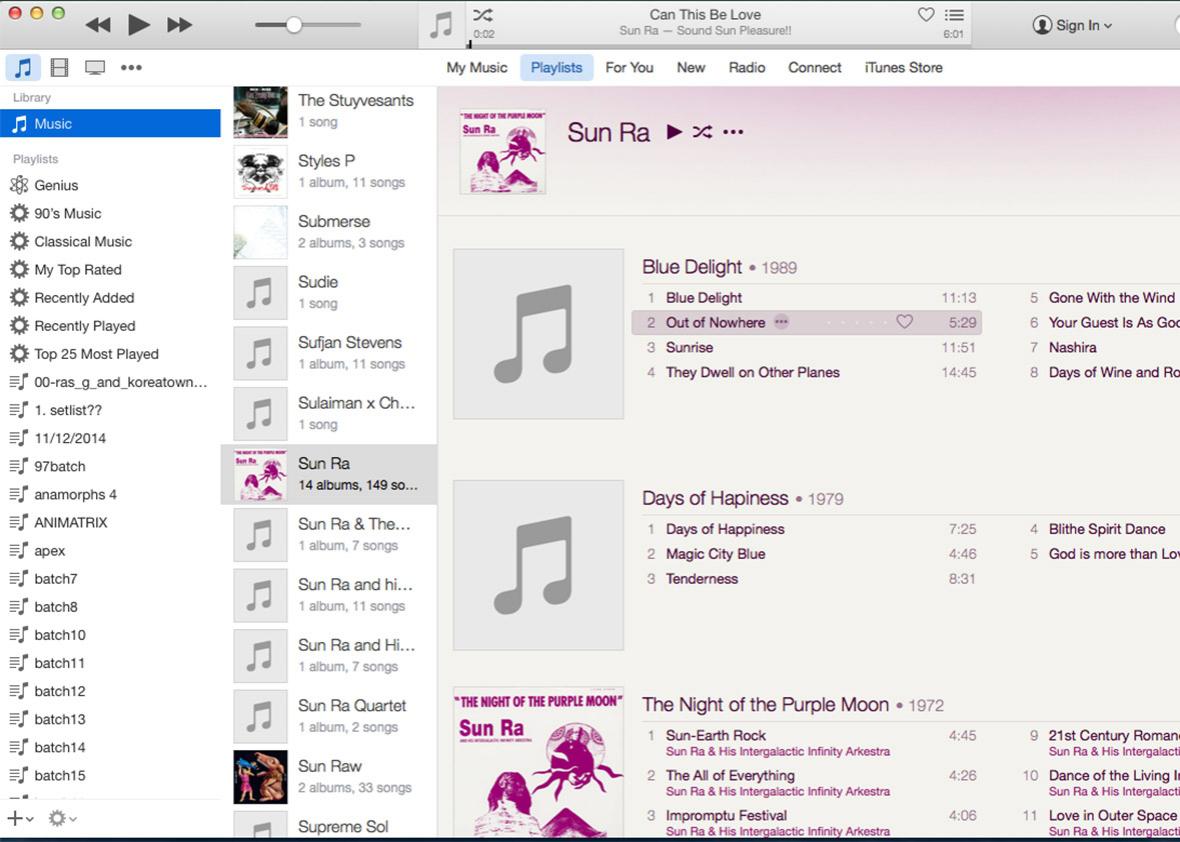

Pinkstone’s blog post filled me with vicarious panic and rage. Here was yet another reason to hate Apple’s music software—something I’d been doing for years, with iTunes as the primary source of my discontent. To date, that discontent had been fueled by the utter disarray in which iTunes had left my digital music library. If what Pinkstone was saying was true, it seemed entirely possible that Apple Music had already started laying siege to what ruins still remained of my once-organized, once-glorious music collection.

It was not always this way. There was a time when iTunes was fine. For a while it even felt like a step up from Winamp, the elegant bit of freeware that I and millions of others installed back when we were using Napster and Audiogalaxy to download music by the truckload. But the digitally encoded honeymoon didn’t last: With the launch of the iTunes store and the phasing out of the iPod in favor of the iPhone, iTunes became the unavoidable command center for managing all kinds of data, not just “tunes” but photos, podcasts, apps, TV shows, and more. As Farhad Manjoo wrote in Slate in 2012, in a piece titled “Won’t Someone Take iTunes Out Back and Shoot It?” the software had become a bloated monster that wasn’t good at doing any of the things that Apple was forcing it to do.

At some point between then and now, iTunes became a total black hole to me. I stopped understanding what it did when I downloaded a song and dragged it into my library. I didn’t get how it related to Apple Music, or what role iCloud played in managing my data. Above all I couldn’t get my head around syncing—the mysterious and maddening process I had to go through whenever I wanted to put specific songs on my iPhone.

None of it made sense to me, and when I thought for too long about the impact iTunes was having on the texture and structure of my music consumption, I was overcome with a bitter sense of loss.

I used to love collecting music. It was a fun, ongoing process that played out over years, and it provided me with an ever-growing time capsule of my taste. Even after I stopped buying CDs—I had amassed a big, proud shelf of them by the time I left for college—I treated my MP3s as my personal property, and I made a point of owning albums and songs that I loved and wanted to remember for years to come. Not to get too High Fidelity here, but my life was richer for having this collection; in addition to reminding me of songs I might have otherwise forgotten and giving me easy access to them, it was a record of who I was.

Reading Pinkstone’s blog post reminded me how much more fractured and less deliberate my music-listening life has become in the age of iTunes. Instead of having a collection that I care for and build over time, I have what amounts to a random pile of files spread across my various devices. These days when I want to listen to music, I consistently just put on either a streaming playlist that’s been curated for me by somebody else, or whichever big album happened to come out most recently, be it Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo or Rihanna’s ANTI.

How did this happen to me? How did I become the equivalent of the guy who, in a previous era, owned eight CDs, one of which was No Way Out by Puff Daddy and two of which were the Beatles’ greatest hits?

Part of the change can be attributed to my age, obviously: People who are 31 generally have less energy for cultivating their musical taste than they did when they were younger. Another part can be chalked up to the rise of streaming audio in general: One could argue that my “collection” now consists of everything that exists on Apple Music and Spotify, which I’ve subscribed to since its U.S. launch in 2011.

Nevertheless I believe that Apple—and iTunes in particular—shoulders more responsibility than anything else for how my listening habits have changed.

At the root of the problem is that the iTunes interface is now designed first and foremost to seamlessly integrate with other Apple products. For worthy reasons, Apple has made it extremely easy to listen to songs you’ve paid the company to listen to, whether you’re a subscriber to its streaming service or a customer in its online store. When I bought the Shamir album Ratchet from iTunes the day it came out, it automatically downloaded to my phone, my laptop, and my work computer. In the year since, I have never had any trouble listening to it, and by virtue of having it in all my iTunes libraries—the one at home, the one at work, and the one in my pocket—it actually feels like I own it.

I can’t say the same for a lot of other music I love, which exists on my devices in a state of abject entropy for the simple reason that it’s not part of the Apple ecosystem. The celebrated 2013 album Acid Rap by Chance the Rapper, for instance, is only available as a free download from mixtape websites; because I didn’t buy it from the iTunes store and cannot stream it from Apple Music, it doesn’t automatically show up in my digital library and I therefore seldom think to put it on. Ditto the trove of classic but never-officially-released diss tracks by Eminem that appeared online between 2002 and 2003, and rarities like the solo Julian Casablancas demo for the Strokes’ “You Only Live Once,” which appeared on the soundtrack for Somewhere.

A truly personal music collection is inevitably going to be full of such odds and ends. But while I’ve owned all the stuff listed above at various points in my life, I don’t have it all in one place, because iTunes has made it next to impossible to do so. At a time when artists have become increasingly generous about sharing stray material with their fans through the internet but never making it available for sale, I have lost the ability to keep track of anything that’s not officially sanctioned.

How I got here, I’m not totally sure, except that on more than one occasion, I’ve had some kind of syncing problem while trying to transfer something to my iPhone, or trying to delete photos or podcasts or movies in order to free up space. Whatever it was I was attempting to do, I must have selected the wrong settings or checked the wrong boxes or hit the wrong buttons while doing it; all I know is that Apple has repeatedly wiped my digital collection clean of all the songs I ever downloaded, except for the ones I had purchased directly from the iTunes store.

That’s how I remember it, anyway. The truth is I am a helplessly unreliable narrator in this story, because whenever I use iTunes, I find that I have absolutely no idea what’s going on, or what the consequences of my actions will be. So while I can’t really be sure how my music collection was decimated, I can say that I went from having a ton of MP3s—many of them downloaded from blogs or directly from artists—to just having the aforementioned Ratchet, Watch the Throne by Kanye West and Jay Z, and a handful of other basically random albums and songs that I happened to buy from the iTunes store.

It’s my fault, obviously. If I were better at computers or maybe just more adept at interpreting the cryptic language that populates Apple’s dialog boxes, my life would probably be different. On the other hand, it’s ridiculous that a software suite from one of the world’s most successful companies is such a minefield, or that the steps required to move files from one of my Apple devices to another has the potential to rob me of everything I own. It doesn’t make sense that everyone I know who still uses iTunes despises it, and that many people, including me, have abandoned it in favor of streaming because managing their libraries became too much of a chore.

In my case it happened gradually and chaotically: Though I do still occasionally seek out mixtapes and stray leaks directly from the web, I’ve mostly just stopped listening to music that’s not available on Spotify. On a basic level, I don’t have a music collection anymore because Apple made it too hard and frustrating to maintain one. And though I certainly deserve some of the blame myself, I can’t help but feel that iTunes has beaten out of me impulses I once cherished, like wanting to download every new mixtape by Lil’ Wayne as soon as it came out, or feeling compelled to own every Smashing Pumpkins album, even though it’s been years since I wanted to listen to them. By making it so difficult to manage my digital music library, iTunes has even closed me off to certain artists I’m confident I would have otherwise loved—for instance, Lil’ B, the ultraprolific rapper who has put out thousands of songs that aren’t available on any streaming service and can’t be bought from the iTunes store.

I’m not saying it’s rational; obviously I could listen to Lil’ B if I really wanted to. And yet the consistently taxing experience of using Apple’s software to acquire, organize, and access my music has dissolved the sense of ownership and identification I once felt toward it. In so doing the company has turned off a part of me that I miss.

* * *

After I read the alarming blog post about Apple Music on Thursday, I decided enough was enough. I was going to figure out how to use iTunes and Apple Music if it killed me.

It almost did. To wit, here’s me after 30 minutes on the phone with an Apple technical-support person who tried her best to lead me out of the darkness:

Leon Neyfakh

Those are hives all over my face, something that usually only happens to me in times of extremely stressful uncertainty. Reading over my notes from the call, I can’t say I’m surprised that this was my body’s reaction, and I definitely can’t say I came away from the conversation with a better understanding of what might have happened to James Pinkstone’s music collection.

Ultimately I did achieve some clarity, thanks almost entirely to an Apple Music expert named, appropriately enough, Serenity Caldwell. Caldwell is the managing editor of iMore, an Apple news site, and the co-author of a whole book about Apple Music; I found my way to her because of a blog post she wrote about Pinkstone’s problem in which she stated, flatly, that the thing he was warning his readers about couldn’t possibly have happened the way he had described it.

What Caldwell made me realize over the course of a half-dozen extremely patient emails is that Apple Music represents a clumsy and inscrutable attempt to blur the line between “owning” a song and merely streaming it. As Caldwell explained it, the app is designed to take the songs you have on your various devices and create backups of them that you can then stream from your own personal cloud.

This is supposed to work even with songs that aren’t available on Apple Music: If I want to listen to Chance the Rapper’s Acid Rap on my iPhone even though the original files only exist on one of my computers, Apple will make a copy of the songs and place them in the cloud. The problem, as I now understand it, is that whenever possible, Apple prefers not to do this—that, ideally, it wants to serve you songs directly from its Apple Music library. This means that if I’ve downloaded Drake’s Views on my work computer in the form of MP3s and want to listen to it from my iPhone on my walk home, the app will provide me with a stream of the Apple Music version of the album instead of saving the MP3s to my cloud and serving me those.

Unfortunately, this sometimes results in mix-ups: In the case of that Fountains of Wayne demo that Pinkstone wrote about, it’s likely that Apple mistakenly identified it as the version of the song it had in its streaming library, and played that instead of the version Pinkstone actually wanted. This is why I’m worried about losing that Popcaan-assisted version of Drake’s “Controlla” that’s on my hard drive: Pinkstone’s experience suggests that iTunes might think the file is the same as the officially released version of “Controlla,” and serve me that as if I won’t know the difference.

But did Pinkstone’s music actually get deleted, as he claimed? Caldwell said she was flummoxed by this, but offered a possible explanation: One thing Apple Music allows you to do, she said, is delete a song from your hard drive entirely and still listen to it on all your devices as a cloud-based stream. The trick is this only works as long as you are a paying Apple Music subscriber; if you cancel your account, the stream will cease to be accessible, and unless you have your original file backed up somewhere, you lose it forever. To its great discredit, iTunes makes it very easy to delete a song off your hard drive without meaning to: Not only are the cloud icons that appear next to each song completely opaque and confusing, it’s possible that a song you’ve deleted will continue to show up in your library, but never give you any clear indication that it’s only a stream as opposed to a local file.

Maybe that’s what happened to Pinkstone. It’s hard to say based on his blog post, and he didn’t respond to an email seeking clarification. Regardless, it’s clear to me that Apple Music is not designed to delete my music and replace it with anything; what it’s designed to do is eliminate the need for me to constantly be syncing my devices with each other. In doing so, Apple Music seems to be holding out the promise of once again letting me keep all my odds and ends in one place.

Now that I’ve wrapped my mind around all this and my hives have subsided, it seems possible to me that I can harness Apple Music’s functionality to actually rebuild that lost collection of mine. It’ll require some getting used to, certainly—there’s something deeply counterintuitive to me about the fact that my devices are all going to contain some songs that are stored locally and some that only exist as streams—but it’s exciting to think that I might once again have the will to start building up a music library.

It sounds perfect, really. But then, so did iTunes. With apologies to Apple, I’ll believe it when I see it. Till then, I’m going to keep nervously checking to make sure my version of “Controlla” still has Popcaan on it.