In 2008, Monster, a tech company known for overpriced cables and zealous litigation against Rhode Island mini-golf courses, teamed up with Dr. Dre, the legendary hip-hop artist and producer who helped bring Snoop, Eminem, 50 Cent, and Kendrick Lamar to the masses. Just five years later you can look around any playground, subway train, or suburban mall to see the result, and it starts with a lower-case b: Beats by Dre headphones have locked down the market.

The numbers are astonishing. According to a recent piece in the Wall Street Journal, Beats revenues increased fivefold between 2010 and 2012 alone, hitting the $1 billion mark. As of this summer, some 59 percent of high-end headphones sold in the U.S. bear the Beats logo. All this despite the fact that the audiophile press has often viewed Beats as underwhelming—or worse—and overpriced. Dre and his co-founder Jimmy Iovine, who together control 75 percent of the company, intend to get Beats not just onto our heads but into our homes and automobiles by expanding into “speakers, audio systems in cars and consumer electronics, and a soon-to-be-launched online streaming music service,” as the WSJ reported.

Consumer electronics have carried famous-name branding at least since Benny Goodman’s 1957 ad for the Webcor Hi Fi Fonograph, but celebrity-created tech has a rockier history. If you’re a fan of certain adventurous electronic artists—industrial heroes Throbbing Gristle, house music wunderkind Nicolas Jaar, or Björk, who never stumbled across a knob or nodule she didn’t want to fiddle with—you can let the music play on their proprietary gadgets and gizmos. But Beats by Dre is the first mainstream option from a bona fide household name to really break through—tech at least ostensibly engineered by celebrities rarely captures consumer hearts. For the U2 iPod, Lady Gaga’s Grey Label collaborations with Polaroid, or Beyoncé’s Samsung B’Phone, check your local landfill.

So how did Dre succeed where others failed? Certainly not through technological innovation. By 2008, shoppers looking to close out the world with music had dozens of extremely well-reviewed options available at every price point and level of audiophiliac desire, from Bose’s noise-canceling QuietComfort 3 ($320) to the geek-chic Koss PortaPros ($40). By contrast, Beats by Dre have received, at best, mixed reviews, with critics complaining of sticker shock, poor sound performance, and shoddy construction. (Seriously, just Google “Beats by Dre falling apart” and read the tales of woe.) While Consumer Reports recently graded the new Beats models rather highly, they tempered their praise by acknowledging that you’re mostly paying for the name and the look, not the sound.

Which is hardly new. Headphones have been as much a fashion statement as a mini-sound-system at least since the canary-yellow Sony Sports Walkman.

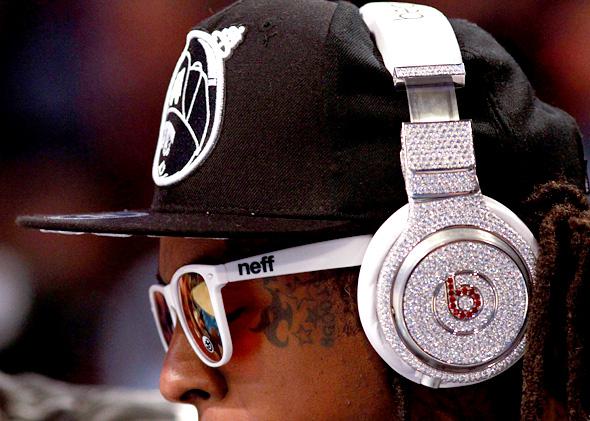

Upstarts like Skullcandy (makers of “the world’s coolest earbud,” per Forbes in 2008) and WeSC (whose wares landed in a Vogue fashion spread) made a mint with a Swatch-like approach to design, featuring big, bold colors in ever-changing combinations. Beats by Dre, for its part, has an instantly recognizable design template; apart from its wireless Bluetooth iterations, Beats’ telltale red cords are the upper-body equivalent of the Louboutin sole.

In the end, though, Dre is selling something few besides him could credibly offer. In a way, he’s selling the same thing he has since the start of his career. Beats by Dre aren’t really cutting-edge technology. They aren’t trendy fashion accessories at heart, either. Beats by Dre are actually bass-delivery systems.

Bass has signified both sex and rebellion at least since Duke Ellington got the ladies on the floor in 1920s. From the rabble-rousing of Sly and the Family Stone’s Larry Graham and Funkadelic’s Bootsy Collins, to Johnny Rotten ditching the treble wail of the Sex Pistols for the dubby rumble of PIL, to American teenagers ditching rock for rap in the late ’80s (and European teenagers doing the same for rave), all the way up to today’s generation waiting for the drop. Bass has always been the quickest way to piss off your parents and dazzle your eardrums.

And few producers have used bass better than Dre. His first hit, J.J. Fad’s novelty masterpiece “Supersonic,” uses a thick bassline the way Coke uses corn syrup, thickening and sweetening the fizz. N.W.A.’s legendary “Fuck tha Police” gained incendiary power from its syncopated booms. Dre’s later G-funk tributes for Snoop and Tupac rely on loping, squinty-eyed basslines for their menace and throb. Birthday-party staples like 50 Cent’s “In Da Club” would be nothing without the low-end bounce.

Lots of headphones offer glorious bass performance, of course. The Beyerdynamic DT 770 has a low-end so crisp and visceral it can give a listener vertigo, though its $175 price point—about half of comparable Beats versions—probably won’t. And plenty of reviewers give Beats’ competitors much higher scores in bringing the bass. A few years ago, Jude Mansilla, founder of audiophile forum Head-fi.org, gave Lifehacker a thoughtful, extensive survey of the current marketplace, using characterizations you might expect of a oenophile, like “full but balanced,” or “neutral tone balance … with none of the bass bloat.” Beats by Dre, however, are all bass bloat. That’s the point. Sharp-eared reviewers expect subtlety and range. Beats’ raison d’etre is to simply blow the lids off the listener. From the entry-level earbuds right up to the studio monitor versions, Beats pummel the ears with bass, often distorting the low-end until it becomes a macho bluster—a roar similar to a standard car stereo turned up to eleven on a hot summer evening.

That feeling, of a bass that cannot be contained, a bass that is too real for your rules, is what Beats delivers. Their sound is hyperbole, and there’s no point arguing with that.

But brand loyalty is a fickle thing, and Dre has wisely roped in other stars for Beats of their own, including the David Guetta–endorsed Mixr and Lady Gaga’s largely ignored Heartbeats. Dre has also made movements toward challenging Spotify and Pandora with his long-rumored Daisy streaming service—although Neil Young, of all people, may beat Dre to the finish line astride his new service, Pono. While its headphone sales set records, other Beats-branded products—mobile phones, speakers, even a Chrysler—have struggled to find their footing.

It’s possible that Dre’s magic—the ritual of wrapping your head in a gleaming status symbol and entering into an existential state of bass—won’t translate to other product categories. It’s a kind of secret ceremony that you can do in public. Who cares if the nerds quibble? Beats by Dre deliver the bombast. People want them, and love them, because bass is the place Dre’s fans want to be.