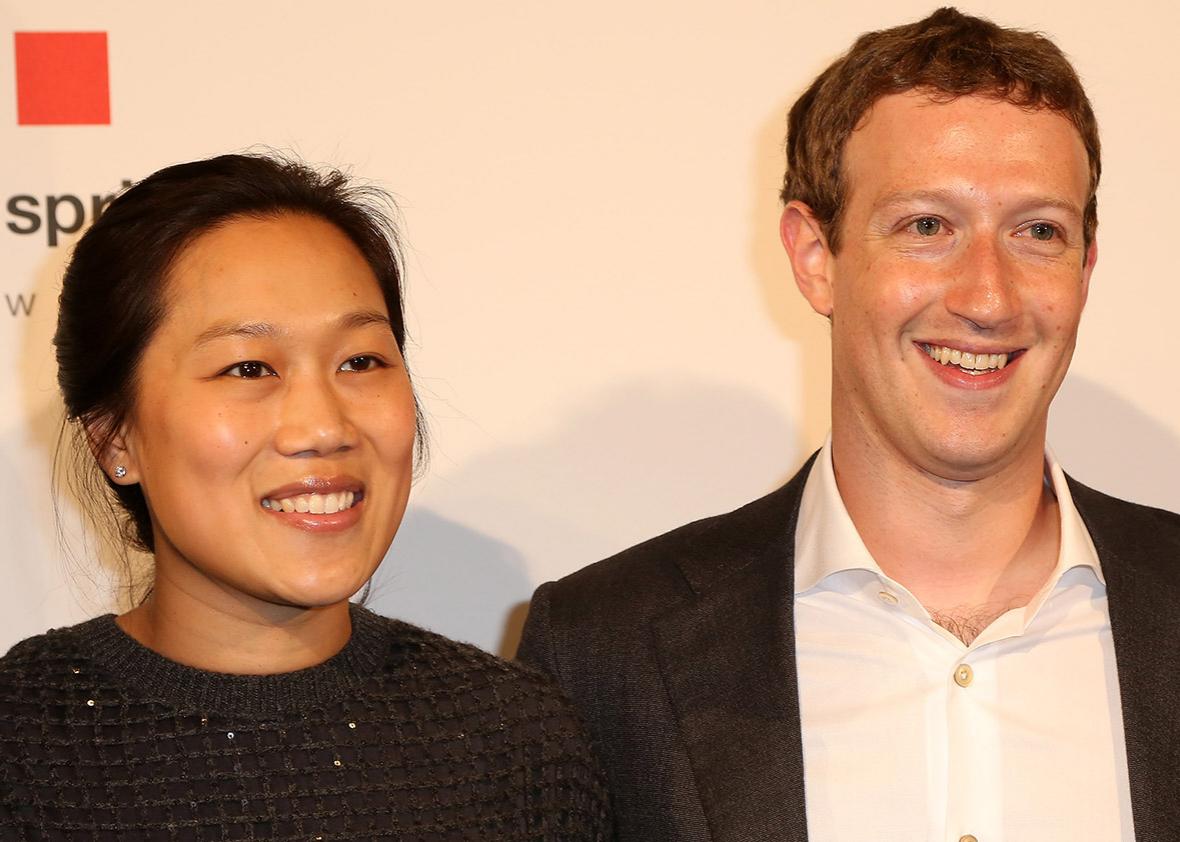

In 1635, the French philosopher René Descartes surveyed the state of human knowledge about health, writing, “It is true that the science of medicine, as it now exists, contains few things whose utility is very remarkable.” But, he predicted, “we could free ourselves from an infinity of maladies of body as well as of mind, and perhaps also even from the debility of age, if we had sufficiently ample knowledge of their causes, and of all the remedies provided for us by nature.” Last Wednesday—381 years later–Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan suggested Descartes’ hope could be a reality within this century.

“We believe we can cure, prevent or manage all diseases within our children’s lifetime,” said Chan. And this type of progress should mean that we see 100-year life expectancies within that time frame, argued her husband, Zuckerberg. To that end, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (fueled by Zuckerberg’s Facebook fortune) is going to donate $3 billion over 10 years to basic medical research, all with the goal of curing disease.

For all that $3 billion sounds like a lot of money, it is underscaled to the ambition: The U.S. National Institutes of Health alone has an annual budget of $32.3 billion. And an estimate of global research and development in health suggested that it totaled $240 billion in 2009. World health expenditure as a whole is about $7 trillion a year, which is more than 23,000 times the size of the annual Chan-Zuckerberg investment.

That said, the goal itself is not as implausible as it sounds at first blush. A 100-year life expectancy within the lifetime of baby Max Chan-Zuckerberg isn’t that much of a reach given past progress. By 1960, according to World Bank data, the average person on the planet could expect to live for about 53 years. Newborns in Norway could already look forward to a life span of 74 years.* In 2014, average global life expectancy had climbed to 72 years, and Hong Kong now has a predicted life span for newborns of 84 years.

Each year, the leading country in terms of life expectancy has seen growth of about a quarter of a percentage point in that expectancy while the average country has seen growth faster than that. If you assume both leading country growth and global convergence continue at a similar pace until 2100, when Max will be 86, leading life expectancy will surpass the century mark and world life expectancy will be very close behind.

So while any claim that last week amounted to a major step forward toward a world where all diseases can be cured, prevented, or managed would still be hubris, that world is not so far distant. The goal is actually reasonable compared with other recent moonshot pronouncements.

Last year, for example, the world’s assembled political leaders agreed to the Sustainable Development Goals at the United Nations. They set targets to eradicate poverty, malnutrition, AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria while providing universal secondary education, access to water, sanitation, energy, and communications for all of humanity by 2030. Those targets are far more ambitious than Zuckerberg’s 100-year life expectancy—requiring global progress that’s simply historically unprecedented across a range of different sectors. And yet no country promised anywhere close to $3 billion to deliver on them at the time—despite the world’s governments having far deeper pockets even than the world’s giants of technology. In selecting a motivating goal, Chan and Zuckerberg have chosen more carefully and done more to deliver.

The tougher call is whether a more focused effort toward a narrower goal would have more of an impact. There are clear examples of where a little bit of money well spent can have an incredibly dramatic impact on a well-selected target. Smallpox eradication is the go-to case: The global cost of the eradication effort (above what countries were already spending in control) was about $300 million over 11 years. That effort has helped spare 40 million deaths and created annual health care savings of $2 billion. A similar strategy is being followed by the Carter Center in its attempt to eradicate Guinea Worm (down to 22 cases worldwide in 2015). The last stage of that program is estimated to cost $225 million—less than one-tenth the Chan-Zuckerberg investment. Then there is a group of donors including Bill Gates and the Rotary Foundation angling to eliminate Polio, which so far in 2016, is down to just 26 cases in three countries, with annual costs for the eradication program running at about $1 billion a year.

The Chan-Zuckerberg money could be used for a similar approach: They could take the lead in trying to wipe out malaria, for example. Or they could tackle the issue of antimicrobial resistance—the National Institutes of Health only spends $310 million a year on that. Given that if left unchecked, antimicrobial resistance could cause 10 million deaths a year worldwide by 2050 and reduce the size of the global economy by up to $100 trillion, it seems like an area that could do with more research finance.

But Chan and Zuckerberg are trying a different angle of attack. Rather than fund elimination efforts for a particular disease or condition, they are funding the development of new approaches and tools that can underpin elimination efforts across multiple diseases, with the hope they will crowd in more money from elsewhere. The finance will be used to support collaboration between medical scientists and engineers to create the tools necessary to diagnose and treat whole classes of illness from infection through cancer—tools like better imaging technologies, a chip that could diagnose all infectious diseases, and a map of every human cell.

The couple argues that this kind of collaborative research aimed at foundational technologies is often overlooked by a funding system that focuses on individual researchers or labs working on a particular treatment or cure. Their funding is also meant to spark a broader movement to fund more science. Zuckerberg suggested: “The more people who believe that we can cure all diseases in our children’s lifetime the more likely we are to get our governments to invest in it and the more likely it is to actually happen.”

It is far too early to say whether such an approach will more effectively save lives than a narrower funding focus. But from one standpoint it is at least a relatively humble approach. Rather than a strong likelihood that they could gain credit as the force behind a particular eradication like Jimmy Carter will and should when the last Guinea Worm is finally wiped out, the best outcome Chan and Zuckerberg can hope for is that the technologies and approaches they fund will contribute in part to a range of eradication efforts that will have to involve an army of others—all of whom could seize the laurels of any victory.

I’ve suggested previously that Chan and Zuckerberg should spend their money on high-risk, long-payoff innovations and initiatives where governments aren’t spending very much. The approach they outlined last week looks precisely like that. While it is too early to know whether it will work, we should all be rooting for its success. If anyone has shown how to leverage investments into stunning and unexpected future returns, it is surely the creator of Facebook.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.

*Correction, Sept. 26, 2016: Due to an editing error, this article originally misstated that Norwegian newborns can currently look forward to a life span of 74 years. That was the life expectancy for Norwegian newborns in 1960. (Return.)