In the fall of 2003, I came to New York City to seek my fortune. I ended up sleeping during most days and drinking most nights at a series of cheap and disgusting bars on Avenue A in the East Village. When I wasn’t drunk or hibernating—and occasionally then, too—I was thinking about the Chicago Cubs.

My move to New York had been underwritten by money I’d saved from working as a Wrigley Field beer vendor, a job I’d taken so I could attend Cubs games for free. At age 22, watching baseball was one of my top priorities, which made me a pretty terrible vendor, since I’d spend more time looking at the game than searching for customers. After clocking out, I would rush to a small patio atop the right-field grandstand, where I’d join a few other young vendors in watching the last few innings out of view from our supervisors. I watched the Cubs clinch a playoff berth from that vantage. I jumped up and down in my uniform, screaming in delight, embracing strangers. The Cubs were making history—and I had been there to see it happen.

I watched every playoff game that I didn’t attend at one of those gross Avenue A bars. It was there, in my brand-new Kerry Wood jersey, that I watched Game 6 of that year’s NLCS—the “Bartman game.” I remember stumbling out of the bar, deeply depressed, and collapsing on a stoop on St. Mark’s Place, where I sat for what felt like an hour, staring at nothing, trying to process what had just happened. I had learned one of the cardinal lessons of Cubs fandom: Try not to care too much.

I moved soon after the playoffs—turns out New York is a pretty unlivable place for a guy with no money and no ambition—and I haven’t been back to those grimy East Village bars since. After 2003, I basically stopped caring about the Cubs. Sure, I wanted them to do well, but I stopped allowing myself to get invested in the fortunes of any given team. I kept working at Wrigley Field, but I started to focus more on selling beer than watching the games. I’m older now, and I can really use the money. The Cubs returned to the playoffs in 2007 and 2008. I barely remember those seasons. I don’t even remember if I was at any of those playoff games.

And then 2016 came around, and I felt 22 again. From start to finish, the Cubs were the best team in baseball, and the skill and joy with which they played the game warmed my cold, shriveled heart. I tried to resist. On June 19, I let my guard down for the first time in a decade. The Cubs were playing the Pirates on a warm, beautiful, clear night. I was selling Budweiser in the left-field grandstand and doing pretty well for a Sunday. Top prospect Willson Contreras had just been called up to the majors, and in the sixth inning he got called on to pinch-hit. As Contreras came to the plate for his first major-league at-bat, I swear to God that I had a premonition: He’s going to hit a home run. He crushed the first pitch he saw into the center-field bleachers. Standing atop section 201, I started crying.

From that point, I was all in on the 2016 Cubs. A couple of weeks ago, I wrote that the 2016 baseball season had made Cubs fans into a bunch of optimists. In that piece, I wrote about Cubs fans as a third party, a group I’d spent the year examining anthropologically from my vantage in the stands. I didn’t mention the extent to which I’d started to care again. I don’t think I even realized it. It became clear to me last week, when the World Series came to Wrigley Field for the first time in 71 years. I worked all three games. “I’d ask how you’re doing, but that’s sort of a stupid question,” I said to a customer before Game 3, as I poured him a $10.50 beer. “I mean, it’s the World Series. And the Cubs are in it!”

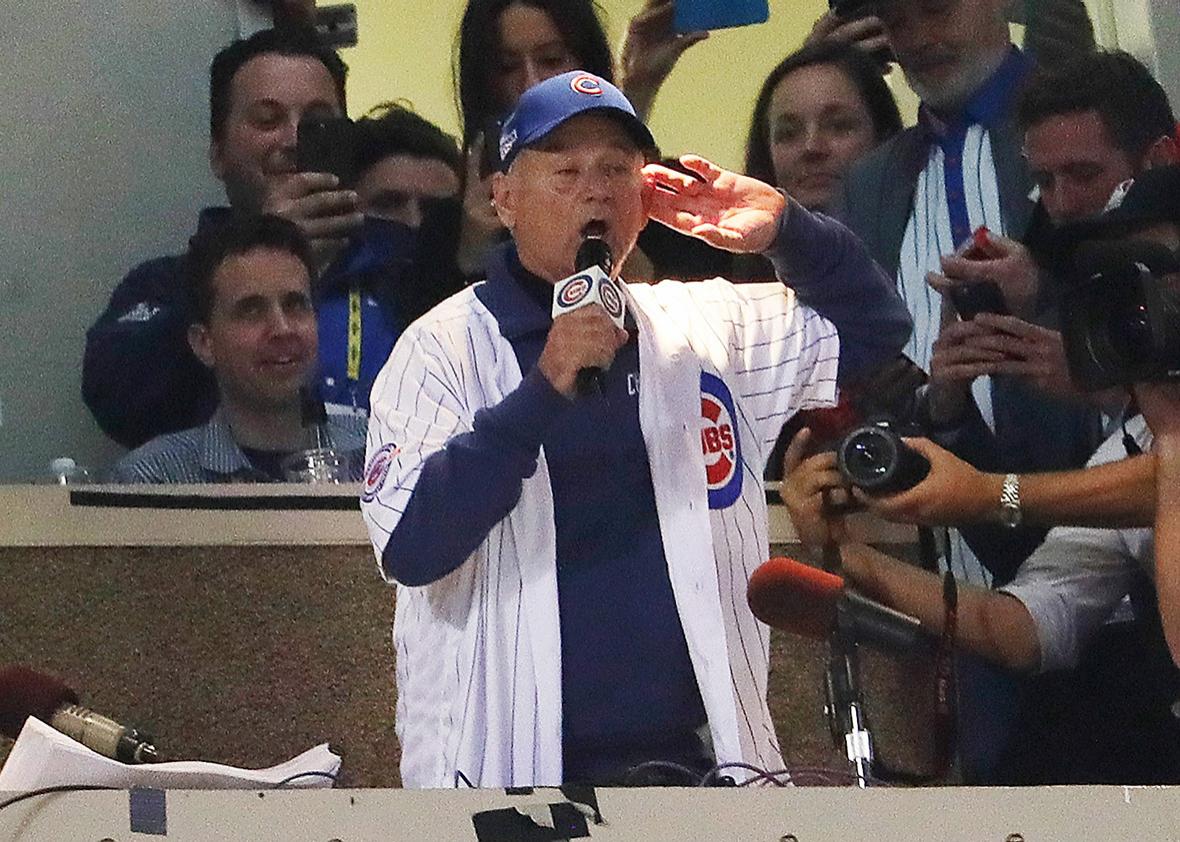

The Cubs hadn’t won a title since the Theodore Roosevelt administration, and people at Wrigley knew they could be witnessing history. The fans had paid a lot of money for the privilege—seats were going for thousands of dollars on the secondary market, and our supervisors reminded us repeatedly to kneel down so as not to block the views our customers had spent so much money to acquire. Celebrity fans abounded: I sold a beer to Bill Murray, who was sitting a few rows down from former NFL quarterback Donovan McNabb, who was wearing a Cubs jersey with his own name and number on the back. About 20 rows up from Murray and McNabb was comedian Jeff Garlin. “Your movie was underrated,” I whispered in his ear as I passed. “Thank you, my friend,” he said. I probably should have specified which movie I was talking about.

Then the Cubs lost Game 3, and the optimism dipped a little bit. It didn’t dip by a lot—it was a very close game, after all—but things were definitely more tense as Game 4 got started. “Yes, we lost yesterday, but we still played good baseball,” I reminded my customers. “The Cubs are still the best team in baseball.” But they didn’t play like it in Game 4. After retiring the side with ease in the first inning, starting pitcher John Lackey surrendered a home run to the first batter he faced in the second. Then, after two successive errors by third baseman Kris Bryant, the Indians scored again. In the top of the third, after two consecutive hits, they scored again, and at that point the mood turned darker. I was selling a beer to the MSNBC host Chris Hayes—who was also wearing a jersey with his own name on it—when Lackey allowed that third run. “Fuck you, Lackey!” he yelled. I felt like joining him.

Downstairs in the vendors’ commissary, the mood was just as glum. “Game’s over,” my co-workers said as they restocked. “They choked. It’s done.” The crowd felt it, too. Around the fifth inning, I watched an upset fan stalk the concourse separating the left-field grandstand from the box seats, trying in vain to energize the quiet crowd. “What is wrong with you people?” he howled. “You need to make some noise!”

By Game 5, the optimism that had characterized so much of this season had curdled into anxiety. I was extremely anxious myself. I stopped looking out for celebrities and completely dispensed with the light banter I had shared with fans before Games 3 and 4. I poured my beers in silence, rarely initiating a conversation. My internal monologue, though, was full of self-recriminations: You let them fool you again, Justin. You let this fucking team fool you again.

And then the Cubs played well, and it was OK to breathe again. By time the seventh inning rolled around, the Cubs were up 3–2 and shutdown closer Aroldis Chapman was warming up in the bullpen. At that point, I had relaxed enough to go up to the musician Billy Corgan and give him a small pep talk. “I appreciate you,” I said, and he had relaxed enough to reciprocate the sentiment with an enthusiastic fist bump. “Never stop,” I said as I walked away. I’m not sure why I said that. It was a strange time.

My vending season was done at that point. I tipped out of the commissary, swiped out of the stadium, and walked down to Schuba’s on Belmont and Southport to catch the final two innings. I pulled up a barstool next to an intense Cubs fan who looked eerily like one of my journalism colleagues. When Chapman struck out Jose Ramirez to win the game and send the World Series back to Cleveland, not-a-colleague and I pumped our fists and exchanged high-fives. “One game at a time,” we told each other. “One game at a time.”

The Cubs won Game 6, which I watched in my apartment, alone. I was prepared to do the same on Wednesday night, until my sister persuaded me to stop being a lamewad and come to Manhattan to watch with her and her friends. I went back to Avenue A on Wednesday night for the first time in a very long time. I donned the same Kerry Wood jersey I wore in 2003, and I went to a disgusting, grimy bar, where I stood next to several hundred other expatriate Cubs fans who all wanted their team to do this thing that none of us had ever seen them do. I offered up my baseball-fan heart. Today, that heart is full.