“Falling Flat: The NFL has lost a lot of its fizz.”

That was the headline of a December 1993 Cincinnati Post article, one that noted that the current NFL season had been “widely ridiculed for so many dull games.” Read from a contemporary vantage point, one in which professional football is not only America’s most popular sport but its last bastion of mass culture, the idea that NFL games were perceived as “dull” seems like blasphemy. Yet, just more than 20 years ago, the NFL found itself at a crossroads. The league had implemented a salary cap and signed an unprecedented television deal with the upstart Fox network. But the on-field product seemed stale. Scoring was down. Offenses were sputtering. The game had lost its mojo. In response to this growing problem, Commissioner Paul Tagliabue and the NFL Competition Committee set out to rejuvenate the sport, and the changes they made created the modern NFL.

From 1983 through 1993, the number of touchdowns scored in NFL games decreased by 22 percent, while the number of field goals attempted rose 14 percent. During the 1993 season, half of the league’s teams averaged less than two touchdowns per game. Average yardage was also on the decline—pro football had become a game of inches. Critics derisively referred to it as the National Field Goal League. Longtime NFL writer Len Pasquarelli, then with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, said pro football had become “moribund” and “stale and predictable.”

Compared with professional basketball, the NFL seemed antiquated, ill-equipped to entertain fans in need of constant flash and action. “The game suffers from a lack of identity and visibility,” Steve Miller, the head of sports marketing at Nike, told Newsweek. Though television ratings remained strong, and Fox had purchased the rights to NFC games for an unprecedented $1.58 billion in December 1993, Tagliabue and the league’s other powers that be felt the on-field status quo was no longer acceptable. The solution they hit upon to make football cool again: Cultivate offense and incentivize teams to go for the end zone rather than settle for field goals.

At the annual owners meeting in March 1994, the NFL’s competition committee passed a bundle of new rules. The committee, chaired by legendary Miami Dolphins coach Don Shula and New York Giants general manager George Young, endeavored to make life easier for offensive players, to discourage the kicking game, and to guide the league into a new technological realm. The changes they pushed through included a renewed emphasis on prohibiting “downfield chucking,” to ensure that defensive backs could not jam receivers more than five yards down the field; giving offensive lineman the option of lining up with one foot behind the line of scrimmage; adding two point conversions; emphasizing the roughing the passer rule, to deter defenders from hitting the quarterback after he released the ball; changing the spot of the ball after missed field goals from the line of scrimmage to the point of the kick; and adding radio transmitters to quarterbacks’ helmets so coaches could talk directly to their field generals.

The NFL had never before approved such a comprehensive package of rules with an eye toward achieving one particular goal. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Tagliabue said the new rules would “have a significant effect in boosting [offensive] production.” Taken as a whole, they painted a clear picture of how Tagliabue and his cohorts wanted the game to evolve. They wanted more offense, specifically more passing, and so they prohibited certain kinds of physical contact on receivers and quarterbacks, thus curtailing defensive players’ ability to disrupt offensive timing. They gave offensive lineman more flexibility to counteract the talents of outside pass rushers such as Bruce Smith and Derrick Thomas, who were wreaking havoc with their unfathomable combinations of size and speed. The implementation of radio transmitters allowed coaches to communicate with quarterbacks in real time. And the addition of the two-point conversion, as well as the field position penalty after missed field goals, made the league’s preference for touchdowns rather than field goals quite clear.

The significance of these changes was not lost upon the cadre of reporters covering the league. The attention they generated, in fact, deflected scrutiny from the other major issue of the 1994 offseason: the newly implemented salary cap of $34.6 million. (In 2014, the salary cap is $133 million.) Fans today may find it difficult to imagine professional football without a salary cap—understanding the cap implications of free agent signings has become a secondary source of entertainment for diehard NFL enthusiasts. But in 1994, the salary cap was a strange new invention, one that led several teams to hire dedicated “capologists” to crunch the necessary numbers. Even so, the transition to the salary cap era was a source of much anxiety. To clear cap space, the New York Giants dumped quarterback Phil Simms just four seasons after he’d led them to a Super Bowl victory, and the Houston Oilers traded Warren Moon after one of the team’s best seasons. As the season approached, Sports Illustrated wrote that it was “time for Tagliabue and the players’ union to admit that the cap can cripple teams.”

But as always, attention returned to on-field issues as soon as the games kicked off. And for Tagliabue and the competition committee, the changes they’d pushed through worked exactly as intended. Scoring increased by 8 percent in the 1994 season, and the passing game soared to unprecedented heights. Teams averaged 214 passing yards per game, the most in NFL history since such team stats have been recorded. A number of individual passing and receiving records also fell. Vikings receiver Cris Carter broke the single-season record for receptions with 122, while 49ers quarterback Steve Young set a new mark for passer rating in a single season (112.8).* Patriots quarterback Drew Bledsoe broke the single-game records for pass attempts and completions, going 45–70 against the Vikings in an overtime victory. Both records still stand. (Bledsoe also set the mark for most pass attempts in a single season with 691, since broken by the Lions’ Matthew Stafford.)

While passing thrived, rushing yardage decreased, which wasn’t terribly surprising considering the new rules did little, if anything, to help running backs. Fans didn’t seem to mind. To the delight of the league’s executives and television partners, the new pass-happy NFL played well with audiences. “Offense in the NFL: It’s Up and It’s Good!” read a New York Times headline.

The preponderance of offense served as a diversion from a series of ugly headlines during that 1994 season. On Oct. 17, 1994, starting Chicago Bears fullback Merril Hoge abruptly announced his retirement after suffering four concussions in six weeks. Hoge was just 29 years old.

While Hoge may have been the most highly publicized casualty of concussions during the 1994 season, he was far from the only one. Less than a week after Hoge’s retirement, Troy Aikman suffered a concussion and lacerated tongue on a hit so brutal that it left Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones questioning whether the league needed additional rules to protect quarterbacks from rough hits outside the pocket. “Barely a week goes by, it seems, without a player suffering a concussion severe enough to cause his coach, teammates, wife, and children serious concern,” wrote Jerry Crasnick in the Denver Post.

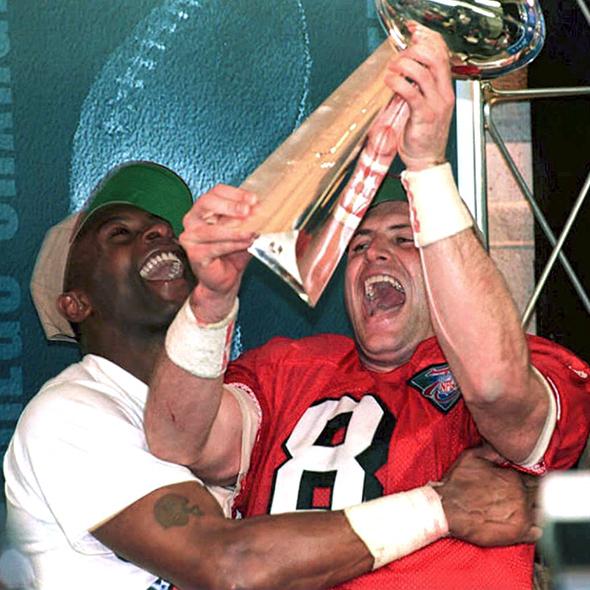

The 1994 NFL season culminated with the San Francisco 49ers routing the San Diego Chargers 49–26 in Super Bowl XXIX. Steve Young , the 49ers quarterback, hoisted the game’s MVP trophy after throwing a record setting six touchdown passes. It was a fitting end for a season that saw offenses, and specifically quarterbacks and receivers, re-establish themselves as the dominant force in professional football. Five years later, Young would retire from the NFL after suffering a reported seven concussions during his career.

In many ways, it’s easy to draw a direct line from 1994 to today’s NFL. The 1994 season was the first in which teams wore throwback uniforms, a persisting trend that subjects viewers to various iterations of the hideous and the sublime. That year, the league’s newest TV partner debuted a graphic nicknamed the “Fox Box,” the first continuous on-screen representation of time and score during NFL broadcasts. (ESPN and ABC used a similar graphic during the 1994 World Cup.)

But the lasting legacy of that season was the decision to stimulate offensive production. Since 1994, the NFL has continued to legislate what defenses can and cannot do, with more emphasis on the latter. Some of the ensuing changes were made in the name of player safety, others as a means to further spark offense. But the result of such tinkering is indisputable. Scoring, total offense, and passing yards have continued to rise dramatically since 1994. Significant individual and team offensive records have fallen. The league is as pass happy as ever, and quarterbacks have become the unquestioned stars of football. In the two decades prior to 1994, just six quarterbacks were taken with the No. 1 overall pick; in the following two decades that number doubled. Meanwhile, the value of the running back has plummeted, with no rushers being drafted in the first round in 2013 or 2014.

Though you’ll occasionally hear complaints that the league has swung the pendulum too far in favor of offenses, such criticism won’t sway the league office. The blueprint set during the 1994 offseason continues to serve as a model for how the league legislates on-field action. This offseason, just a few months after the Seattle Seahawks’ aptly named “Legion of Boom” secondary dominated opponents en route to a Super Bowl victory, the league took a page from the 1994 playbook and announced that officials would be cracking down on illegal contact between defensive backs and wide receivers.

It’s about as likely, then, that Commissioner Roger Goodell will push for rules to stymie Peyton Manning and Tom Brady as it is that he’ll declare football too dangerous for America’s children. This is the age of fantasy football and the NFL’s RedZone channel, both of which can only thrive when players score touchdowns in bulk. Today’s era of offensive football got its start 20 years ago, and it’s here to stay.

Correction, Sept. 4, 2014: This article originally misspelled the first name of wide receiver Cris Carter. (Return.) Also, due to a production error, the photo caption in this article misspelled the name of the Vince Lombardi Super Bowl Trophy.