The Motorcycle and the Rumor

After his first five seasons in the NBA, Delonte West was the kind of player who basketball obsessives knew and loved, a fan favorite who hadn’t drawn much mainstream attention. That changed on Sept. 17, 2009. Around 10 p.m., not far from his home in Prince George’s County, Maryland, he was pulled over on his three-wheeled Can-Am Spyder motorcycle for making an unsafe lane change. West explained to the officer that he was carrying weapons: a 9 mm Beretta, a Ruger .357 magnum, a Remington 870 shotgun, shotgun shells, and a bowie knife. The police later reported that the shotgun was in a guitar case.

Photo by Christian Petersen/Getty Images

By the next morning, West had ceased to be an ordinary NBA player. The website Rotoworld cited Terminator and Raising Arizona. Everyone else brought up El Mariachi, the Robert Rodriguez film that features a motorbike, a guitar case, and a whole lot of weapons. “This is not a simple case of terrible behavior. West is clearly a disturbed person,” declared the Examiner, citing West’s diagnosis the year before with what had been described in the press as a mood disorder. That diagnosis had been fairly minor news, and West had gone on to have his best NBA season to date. But now the clinical label offered, or seemed to offer, an explanation for an outlandish story. At the Cleveland Cavaliers’ media day, West said that people would eventually understand that the highway arrest was “not as big as some are making it.” But he was advised by his lawyer not to talk about what happened until after the trial, which was postponed until the following July. For the rest of the season, West did not speak to the media at all.

That year was a difficult one for West. Two months before the arrest, he’d married his college sweetheart. A month after the motorcycle incident, they were divorced. He also lost his starting spot on the Cavaliers. But despite these ups and downs, West played well, and the Cavs went into the playoffs with the NBA’s best record. Then Cleveland’s (and the world’s) best player, LeBron James, played less than his best against Boston, and the Cavs lost the Eastern Conference semifinals in six games. Not quite two months later, James went on television and said he was taking his talents to South Beach.

Why did the Cavaliers falter in LeBron’s final playoff run with the team? The day after Cleveland bombed out of the postseason, an email began to circulate among sports fans. “I was just told from my brother that a very reliable source informed my uncle that Delonte has been banging [LeBron’s mother] Gloria James for some time now,” reads one version of the email. “Somehow I guess LeBron found out before game four and it has destroyed our chemistry and divided our team.” Other iterations of the gossip sourced the rumor to “someone who works at a law firm that deals with sports litigation,” “David Stern’s office,” “my dad and his friends in Cleveland,” and the general contractor for the Cavaliers’ arena.

A gossip site ran the story, prompting a cease-and-desist letter from James’ lawyer. “No thinking person could possibly believe such rubbish,” said the letter, which declared the story “categorically false and per se defamatory.” After James left the Cavaliers to sign with the Miami Heat, ESPN’s Bill Simmons suggested on his enormously popular podcast that the rumored dalliance could explain why James left Cleveland. “It does make you wonder,” Simmons said. “Something happened.”

Simmons’ seal of approval helped give credence to an entirely unsubstantiated rumor. Why were so many people willing to believe a story that’s never been backed up by any evidence? For one thing, it provided an explanation, albeit a rather baroque one, for James’ baffling playoff performance. For another, it was salacious, a tidbit that people wanted to be true because it was so juicy. But the gossip also gained traction for another reason: the perception that West was “crazy.”

Photo by Aaron Josefczyk/Reuters

The same week that Simmons recorded his podcast, Matt Taibbi wrote in Rolling Stone that he believed the “unconfirmed” rumor because he would “believe any story involving Delonte West.” Taibbi’s story, a roundup of “the weirdest dudes in sports,” ran under the headline, “Freaks of the Game: The Good, the Bad, and the Insane.” The Rolling Stone item echoed a 2004 column in which Bill Simmons coined the term “The Tyson Zone,” a phrase he used to refer to celebrities like Mike Tyson, Dennis Rodman, Ron Artest, Gary Busey, and Paris Hilton. No matter what you heard about this group of people, Simmons wrote, you wouldn’t hesitate to believe it. In 2010, Delonte West entered the Tyson Zone.

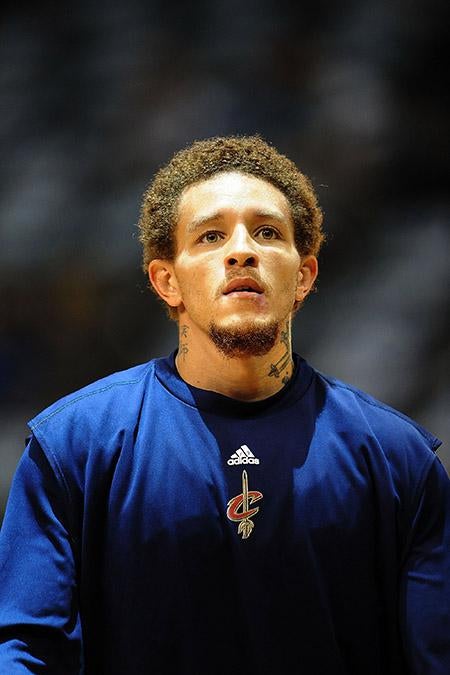

He had, in other words, become a joke, and that joke had serious consequences. West, who turned 30 last July, has now been out of the NBA for two seasons. It’s fair to ask why someone with his abilities, a player who has spent the last year proving himself in the basketball hinterlands, finds himself on the outside looking in. West doesn’t know why he can’t get a job in the NBA. He just wants you to remember that when you’re chuckling about LeBron’s mom and a gun-laden motorcycle ride, you’re laughing at a human being—“a person who plays basketball,” not just a basketball player.

After Sept. 17, 2009, people said that West was like a character out of El Mariachi. It was a joke that may have concealed a deeper truth. Robert Rodriguez’s film is about a case of mistaken identity. The protagonist, a young guitar player, dreams of making it as a musician. Instead, he’s confused for a criminal, a man whose hallmark is a weapon-laden guitar case. When the mariachi rides off on a motorbike at the end of the movie, his dream of a life in music has been destroyed. That’s how West describes the last five years of his life: He was mistaken for a person he never was, and his livelihood was taken from him. He hopes that isn’t how the story ends.

The Deep Water

A Texas Legends home game feels like an extravagant birthday party thrown for the most popular kid in suburban Dallas. Frisco, a well-to-do bedroom community, has tripled in size as families with children move farther from the city, and those kids are the Legends’ key demographic—hence the bouncy castle a few yards from the court. It’s April 2013, and the Legends, the NBA Development League affiliate for the Dallas Mavericks, are playing the Springfield Armor. West, who signed with the Legends a few months before, is easily the most famous player on either team. He saw a stint with the Legends as a path back to the Mavericks, who had cut him the previous October. Then Mark Cuban, the Mavericks’ outspoken billionaire owner, told a reporter that West wasn’t welcome on the big club anymore. West eventually decided to report anyway, with the aim of impressing some other team. But at the moment, to an onlooker sitting courtside near a bouncy castle, the NBA seems very far away.

Regardless, the level of play here is high, better than top-notch college basketball and with less all-out chucking than you might expect from a league where every player hopes his stats will catch the attention of NBA scouts. The game is close, and West keys a third-quarter comeback with a couple of steals, nifty passing, and some timely baskets. His play helps the Legends to a close win, though the box score shows only a pedestrian stat line. After the game, West gets mobbed by kids, happily signing this teenager’s forehead and that toddler’s T-shirt, smiling for pictures with children and their parents.

The next day, before the season’s final game, he’s the last player to arrive in the locker room and the only one who doesn’t introduce himself to me when he walks in. He knows why I’m there, and he has, over the years, become justifiably skeptical of the press. As he gets ready, he jokes with his teammates that with the media present—just me—they better get their Braveheart on, pretending for a moment to launch into a rousing motivational speech.

Photo By Raymond Boyd/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

In conversation, West is quick and can be very funny, with an off-kilter sense of humor that can throw off earnest media types used to the more staid interview styles of his athlete brethren. In 2006, West gave a Valentine’s Day interview in which he described his ideal date, an evening featuring an all-white wardrobe, a yacht, and Popeyes chicken. A few years later, he made a star turn on Jim Rome’s TV show, describing his rookie teammates’ failure to get him three dozen hot Krispy Kreme doughnuts. (“Trains, planes, and automobiles,” West tells one of the rookies, offering him some traveling options. “You better have my doughnuts.”) Asked early in his career what he did in his spare time, West, who studied art in college and was serious about painting, said, “I like to paint murals of the ocean that I see beyond the horizon, because I feel if—in order for us to grow, we gotta know. In order to love the brother man, you gotta know the other man. One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish. Knick knack, paddy whack, give a dog a bone. Ding.”

West’s sense of humor endeared him to NBA fans, though some didn’t seem to realize that West was laughing along with them—that he was the one making the joke. For a long time, that sort of misperception seemed harmless enough. A video that he and a friend made that showed them freestyle rapping while waiting on some KFC chicken, for instance, was mostly beloved. If some people found it ridiculous, that didn’t seem terribly consequential. But when West got arrested, it didn’t help his cause that he’d said a bunch of odd, funny stuff on camera. It didn’t take much—the events of a single night—for “wacky” to transform into “crazy.”

Several months after our brief meeting in the Legends’ locker room, I got West on the phone, and eventually we spent much of an afternoon together at his home in Prince George’s County, Maryland. West grew up in and around P.G. County, and he speaks with a distinctive Mid-Atlantic drawl that doesn’t sound like anyone else. (His pronunciation of “wire hanger” in a promo spot for the Celtics was a particular favorite in the Boston area.) His parents divorced when he was young, and his mother worked multiple jobs, combining government work with bagging groceries and a receptionist’s gig at a hotel where, as it happens, visiting NBA teams sometimes stayed when they came to play the then–Washington Bullets. West recalls throwing his ball at one team’s bus, to “let ’em know I’m playing, too.”

West has an older brother, a younger sister, and a vast extended family that he refers to as “a village.” He stayed with many of those relatives growing up. “I lived off of every exit,” he says, rattling off 11 specific ones from memory. “I lived in so many apartments … with cousins, uncles, and aunts, just making it.”

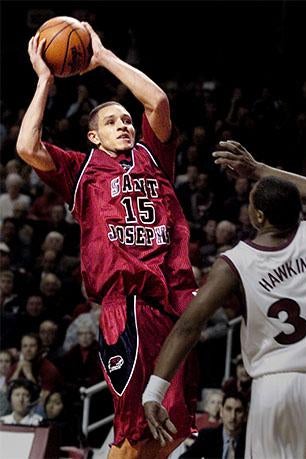

West was recruited by a few different colleges but chose St. Joseph’s because it had a “family atmosphere.” There he played beside future NBA All-Star Jameer Nelson, and as a junior helped lead the Hawks to an undefeated regular season and a run to the Elite Eight in the 2004 NCAA tournament. West then left for the NBA and was drafted late in the first round by the Celtics. Despite breaking his thumb just before his rookie year—the sort of injury that West, who plays with abandon, has suffered often—he earned the backup point guard spot in Boston behind fading Hall of Famer Gary Payton, combining his already reliable jump shot and aggressive defense with better-than-expected playmaking. The left-handed West moves in a funky way on the court—on purpose, he says, to keep defenders off-balance. Right away, he appeared confident playing with veterans. “He doesn’t look like a rookie,” wrote the Boston Globe’s Jackie MacMullan in March 2005, near the end of his first season. “[H]e’s fun to watch, his energy is contagious, and he just seems a little more mature than most NBA kids.”

West wasn’t as mature off the court. When he talks about jumping to pro basketball, the metaphor he returns to is “the deep water,” as if he’d been tossed into the sea and could barely stay afloat. “I basically wasn’t as grown as I gave myself credit for, or as much as I wanted to be,” West says. He believes that big NBA paychecks—his rookie contract paid him about $1 million a year—and the lifestyle that that money encourages can “slow up that process of growth.” A lot of players use the money to relive their younger days, he says, trying to make their childhoods better a second time around. “So what’s the first thing? You’re going to get every video game you ever wanted. Then you put your video game inside your car.” But it can be a lonely life. Many players bring old friends along, paying their ways in exchange for doing chores like buying groceries. This may work fine at first, West says, but “give it two more years, and you’re two grown men sitting down, and he’s more like, ‘Go get you some eggs? You can’t get your own eggs?’ ”

West brought his older brother, Dmitri, with him to Boston. Dmitri, though, had already met the woman who would become his wife. West came home from practice one day, and his brother had left, gone back to Washington, D.C., to get married. He told West that the NBA lifestyle wasn’t for him. West admires him for it. “Best decision of his life.”

West spent three years in Boston, and he played well, becoming a starter in his second year and playing in the NBA’s Rookie-Sophomore Game in 2006. But he sometimes argued with coaches and didn’t always take criticism well. When he got frustrated, he found it difficult, despite his verbal facility, to put his feelings into words. “That’s just from how I was raised—it’s not something I would sit down and do. If something frustrated you, or you got into it on the basketball court out there, you would fight, and then it’d be over. No one really showed me how to sit down and discuss my feelings and what exactly is bothering me.” Instead, “it would build.” West says he got a lot better at dealing with his anger in those first few years, learning from people like then-Celtics coach Doc Rivers. West says he always appreciated that Rivers “communicates to you, even on the court, like a person.”

After three seasons West was traded to Seattle as part of Boston’s deal for All-Star Ray Allen. The Sonics were struggling, and West never got as comfortable there as he’d been with the Celtics. Just a few months later, in February 2008, he was traded again, to the Cleveland Cavaliers. There his ascent resumed. He became a starter on a team that, in the Eastern Conference semifinals, fought eventual champion Boston for seven close games. West played more minutes in that series than any Cavalier save LeBron James, had the second-most assists on the team, and was third in scoring. In the offseason, Cleveland signed him for two more years, paying him about $4 million per season, with a team option for a third year.

Just a few weeks later, in October 2008, West blew up at a high school referee who was officiating a preseason scrimmage. “I felt a feeling of anger and I just wanted to throw it all away and quit the team,” he told reporters soon after. “I needed help.”

West took a few days off and saw a therapist. When he returned to the team, he told the press he’d been dealing with a mood disorder. Later, he’d describe it as bipolar disorder. “In a sense, you feel like a weaker man, because you have to raise your hand and ask for help,” he said then. “But I found out over the last week that it made me a stronger person. I came back focused, and with the help of some medicine and talking with people on a regular basis, I’m back in good spirits.”

By all accounts, getting help was a great move for West, and his decision to speak openly about his inner turmoil took a lot of courage. But anyone who goes public with his psychological struggles—especially in the sports world, where open and honest discussions of mental health issues are still rare—has to worry that people will judge him, laugh at him, and treat him differently. All three of those things happened to Delonte West.

“Crazy in a Good Way”

Psychiatrists have been diagnosing an illness characterized by depressive periods and manic episodes since the 19th century. It was known for a long time as manic depression. Now it’s called bipolar disorder. Diagnoses of the illness became much more common after 1994, when the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders added Bipolar II and “bipolar disorder not otherwise specified” (BD-NOS) to its long list of classifications. Bipolar II and BD-NOS are less severe than what is now called Bipolar I, and bipolarity is widely considered to exist on a spectrum. Some people experience severe depression and mania that includes hallucinations, while others have much milder symptoms. There are those in the field who believe the illness is now overdiagnosed.

West was diagnosed as bipolar by a D.C.-area specialist. He says that when he saw the doctor, he’d been feeling down, having days when he was sad and tired and didn’t want to get out of bed. But he told the specialist that there were also times when he “might just go out and buy a car. Or go to the mall and spend 25 grand.” West doesn’t think the doctor took into consideration that such behavior might not be unusual for a professional athlete with a big paycheck. He now thinks that he was suffering a temporary bout of depression, not exhibiting symptoms of a chronic disorder.

Photo by Doug Pensinger/Getty Images

I haven’t spoken with the specialist who treated West. I also don’t have any training in psychology or psychiatry. Then again, neither do most sports writers. Some people who covered the Cavaliers, like the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s Brian Windhorst, acknowledged after West’s arrest that the player’s behavior defied simple explanations. When West erupted in anger at a reporter early in the 2009–2010 season, Windhorst and others left it out of their stories, partly, he says, out of sensitivity for what West was dealing with—though of course staying mum also coincided with the team’s interest in keeping negative incidents out of the papers.

Scott Raab, the author of the anti–LeBron James manifesto The Whore of Akron, was later critical of those reporters who chose not to speak up about West’s locker room blowup. Writing in Deadspin, Raab flatly declared that West had been “off his meds.” Raab, though, is a model of sensitivity compared to Peter Vecsey, who asked his New York Post readers to “consider the fact West has depression problems and suffers from mental illness.” Vecsey continued, idiotically: “What prevents him from concealing weapons in his Cavaliers workout bag and sneaking them into the arena or practice complex, and, on a particularly moody blues day, blasting everybody in sight?”

In West’s view, the press felt more comfortable assigning him to a category than trying to understand him as an individual. For many sports writers and fans, the clinical label became an easy explanation for anything he did that seemed out of the ordinary. In the season following his arrest, he was frequently silent and somber in the locker room, but West doesn’t believe a disorder is the best explanation for this behavior. He was worried that he might get serious prison time for the weapons charges. He had married and then divorced his college sweetheart. He says that negative thoughts went through his head every day: “I’m just going to go home, man. Turn myself in now. I don’t even deserve to play basketball this year, man. I’m too embarrassed, man. I can’t deal with the laughter.”

West says he’s been fighting through these feelings of shame and humiliation since he was a child. He doesn’t regard them as all that unusual, or even as totally harmful. In fact, he thinks this relentless negativity helped drive him to become an NBA player.

Glen Farello, who coached West in high school, says his former star player was blessed and cursed with “the competitive nature of great players.” Farello told me about a basketball camp where a teenaged West played on a randomly assembled team of his peers, most more concerned with impressing the college coaches in attendance than with winning games. Farello found West on a bench alone, and he asked him if he was hurt. “He looks up at me with tears in his eyes,” Farello says, “and he goes, ‘Coach, we lost by two. It shouldn’t have happened.’ ” What made West special, his old coach suggests, could sometimes become a problem. “At times, his competitiveness gets the best of him.”

Farello’s words were echoed by others who have worked with West. Danny Ainge, who drafted the St. Joseph’s star for the Boston Celtics, told me that in his 35 years in the NBA, West is among the top five players he’s “ever been around in terms of competiveness.” Phil Martelli, who coached West at St. Joe’s, says one NBA team told him that “they had never seen a competitive streak” like West’s on the psychological testing they conducted prior to the draft. Like Farello, Martelli thinks that the trait can cut two ways. He believes West’s competitive streak is “the reason he was in [the NBA] and was successful—and also I think it’s his greatest weakness.” “He’s got that dog in him,” his teammate in Cleveland and Boston, Shaquille O’Neal, said to Scott Raab, explaining West’s fierceness on the court. Asked in Boston about West, O’Neal told reporters, “You guys think he’s crazy, but he’s not.”

West has a formidable work ethic. He has also, in the past, become fixated on failure, and channeled that frustration in a way that he later came to regard as unhealthy. After missing a potentially game-tying three-pointer while with the Celtics in 2010, West told reporters, “When I was younger and I didn’t have the proper care and medicine, I would’ve been in here all day.” Mike Malone, an assistant coach with the Cavaliers while West was there—he’s now the head coach of the Sacramento Kings—told me that when West became a distraction in the Cleveland locker room, it was because he couldn’t move past small frustrations and injustices. If there was a bad call in a scrimmage, for instance, “he had a hard time letting it go.” At St. Joseph’s, West would call assistant coach Monte Ross as late as midnight and ask to be let into the gym, and he would tell Ross the next day that he had been putting up shots until 3 or 4 a.m. His roommate and teammate Dwayne Jones, who later played with West at multiple stops in the NBA and in the D-League, says West sometimes spent the night there.

By putting in these all-night sessions, West, who was not the top prospect on his high school team, “made himself into a professional basketball player,” Ross says. West says something similar, but more pointedly: “I know that’s how I became a professional athlete. I was always so hard on myself, almost to a fault.” Or, as Brendan O’Connell, an assistant coach on West’s high school team, has put it: “If he’s crazy, when it comes to practice, he’s crazy in a good way.”

Photo by Chris Graythen/Getty Images

There is no shortage of professional athletes who hate losing and will practice obsessively to avoid failing the next time. What’s striking is the suggestion, made again and again, that the same traits that can be destructive on a personal level can fuel greatness on the court.

The sports psychologists and psychiatrists I’ve spoken to say that having healthy mental habits and attitudes outside of competition will help an athlete perform better on the field of play. But most also acknowledged that athletes can channel otherwise harmful tendencies—obsessiveness, aggression, anxiety—in ways that benefit them as competitors. Dr. Thomas Eppright, a psychiatrist who worked with West in Cleveland and has stayed in touch with him since, makes the point bluntly: “Some of the greatest athletes who have played any sport were not healthy human beings, mentally.”

Eppright doesn’t mention Michael Jordan, but perhaps he doesn’t need to. Last year, Wright Thompson profiled Jordan for ESPN the Magazine, reflecting at length on Jordan’s “competitive rage” and what Thompson calls Jordan’s “most valuable and destructive traits.” Jordan reportedly punched more than one teammate in practice, and he went after others verbally. But these were just the costs of working with the greatest player in NBA history. Jordan was always the best player on his team, and his teams usually won. In the media’s view, Jordan was not “crazy.” He was a winner.

In his ESPN profile, Thompson points out an overlooked line from Jordan’s infamous Hall of Fame speech, the one in which he named seemingly every person who’d ever slighted or doubted him. In that speech, the six-time NBA champion referred to basketball as his “refuge,” the “place where I’ve gone when I needed to find comfort and peace.” This is how West, too, talks about the game. As a kid, moving from school to school, he often found himself the target of playground taunting. “I was real funny-looking,” he says, with big ears, a mole on the back of his head that he had removed once he got to the NBA, and a birthmark below his lip that he’s also had partially removed. His light skin and red hair stuck out, too. “I was made fun of a lot growing up, but I just knew the basketball court was the place where you couldn’t make fun of me, you had to respect me.” He says he always had “more jokes for me than you had,” but that he internalized the cruel things kids said to him. Last year, West told an interviewer that he believed his real problem was not bipolar disorder, but “self-loathing.”

Photo by Brian Snyder/Reuters-Paneikon/MED

After the arrest on the highway and the online joking and derision that followed—and, especially, after the rumors about him and a teammate’s mother—the feeling that he was being made fun of returned. “My sanctuary, my place of peace, became the joke of my life,” he said in 2012. “Right now I’m just a guy who’s trying to stop getting laughed at.” He came back to the same point in an interview a year later. “When I played basketball, because I worked so hard, it’s always been the one place where people couldn’t laugh at me. All of a sudden the laughter is now coming from the mainstream. Everywhere I look, the joke is on me.”

“I Don’t Think That I Am Bipolar”

Those jokes started with his arrest in 2009, which changed West’s image from that of a scrappy player with a big personality to a gun-toting desperado. But West’s account of that night is much less dramatic than how the event came to be depicted.

It was the offseason, and a few of West’s cousins had come over to his house with their children. West’s mother was looking after the kids while he slept and the other adults went out. At some point in the evening, West’s mother woke him up. She said the kids had gotten into a closet in his small, in-home music studio, where he stored guns that he had bought, legally, in Cleveland. He needed to do something about those weapons, she told him.

With the driveway crowded by his cousins’ cars, West got on his motorcycle so he could bring the guns to another residence. Earlier in the evening, he’d taken Seroquel, which is often prescribed for bipolar disorder. Seroquel makes you drowsy, and as he headed out on the highway, he found that he was dozing in and out. After he felt himself drifting off, West was pulled over for making an unsafe lane change, and he told the officer that he was carrying weapons. The day after the arrest, a police spokesman said that West was “very cooperative the entire time.”

West has said all this before. It was the explanation his lawyer offered to the state of Maryland, and it echoes what a friend of his told a reporter two months before his case was settled. At the sentencing hearing, the state’s attorney explained to the judge that, in reaching a plea agreement with West, he took into account “his mother’s statement that he was moving the weapons from one residence to the other,” as well as West’s lack of any adult criminal record. (It’s legal in Maryland to transport guns between residences, but there are rules about how one may do so.) West pleaded guilty to two misdemeanors—unlawfully carrying a dangerous concealed weapon and unlawfully carrying a handgun—and he was sentenced to house arrest, unsupervised probation, counseling, and community service. For all the Internet attention to the shotgun, there were no charges related to that weapon: West was fully within his legal rights to carry it. West also claims that he wasn’t holding the shotgun in a guitar case—that it was more like a duffle bag.

Given the way West’s motorcycle ride has been depicted—it’s a scene right out of El Mariachi; he’s “clearly a disturbed person”—this is a relatively unremarkable series of events. He was not violent. He did not require any medical attention. There does not seem to be any evidence that he was suffering from a mental health crisis.

Even so, after the sentencing, Cleveland—which, having lost LeBron James, was entering a rebuilding phase—declined its option on West’s contract. He settled for a one-year, nonguaranteed deal back in Boston. On account of the misdemeanor convictions, he was suspended by the NBA for 10 games, and he spent the entire season on house arrest—he could practice and travel with the team but otherwise could not leave his home. He missed much of the season with a broken wrist, and the Celtics lost to the Miami Heat, James’ new team, in the 2011 Eastern Conference semifinals. The playoffs were followed by a leaguewide lockout. While other players took jobs overseas, West was not yet allowed to leave the country.

Photo by Harry How/Getty Images

When the NBA got back to business, he signed another one-year deal, this time with Dallas. Lawyers’ fees stemming from both the arrest and his divorce had depleted what was left in West’s bank account. He had already bought homes for himself, his mother, and his father. He had put his sister through college and bought her a car, among other acts of family-oriented largesse. (He’ll “borrow a dollar just to give you a dollar,” says his brother, Dmitri.) When he got to Dallas, he had trouble finding an apartment he could afford, and he was spending some nights in his truck, parked in the arena’s garage. One night, he says, he Googled himself on his phone after a good game and got upset when he found a story that brought up his arrest. Frustrated, he wrote a series of angry tweets, saying that he was sleeping in his car because he’d been treated shabbily by the media—that he’d gone from starting on a team that won more than 60 games to being “a desperado” making the league minimum, and now people wouldn’t rent him a place to live because of “shit they read on the internet.” The tweets devolved into angry profanity targeting a particular journalist. He later deleted the posts and apologized.

A night of frustrated tweeting will reflect poorly on any prominent public figure. When, like West, you have a mental health diagnosis, it becomes an “episode.” A writer at Deadspin concluded that West’s inability to go with his team to the White House—the Mavericks had won the championship the season before—“triggered something in Delonte (who suffers from bipolar disorder),” and that this had prompted the Twitter rant. Later in the season, West stuck his finger angrily in Utah forward Gordon Hayward’s ear. This, too, went on the “crazy Delonte” ledger—or the “crazy Delonte” slideshow, perhaps, like the one published by Complex in 2010, which listed his arrest and the Gloria James rumor alongside funny ads and colorful interviews he’d done. This is what happens when the Internet decides you’re crazy. See also the 2013 listicle from the Daily Beast devoted to Metta World Peace’s “7 Craziest Moments,” from the time that World Peace (who then went by Ron Artest) fought fans in the stands to the time he thanked his psychologist after winning a championship. West and World Peace are both on the Business Insider list of “The 20 Craziest Players in the NBA”—“the league is filled with more ‘crazy people’ than any other sport,” the author claims—along with 18 other men (including J.R. Smith, JaVale McGee, and Matt Barnes) who at one point said or did something unusual.

In the beginning, West embraced his diagnosis. He had set up a foundation when he got to the NBA, and he decided that helping bipolar young people would be part of its mission. He spoke openly about the condition, his work with an NBA-appointed psychiatrist, and his continued relationship with Dr. Eppright in Cleveland. After the league fined him for putting his finger in Hayward’s ear, calling it “a physical taunt,” West spoke of experiencing “a trigger point that took me from one extreme of happiness to more of a depressed state.”

He now says that he always doubted that he was really bipolar but that he wanted to serve as a role model and turn the diagnosis into something positive. In his view, the stress surrounding his divorce and his arrest reversed the maturation process he’d started in Boston. He fell back on older habits, keeping things to himself and balling up his feelings. “Being a little older now, and looking back, you see things would have been a little different if I just told them what was really bothering me: ‘I don’t think that I am bipolar. That medicine that you’re giving me, I don’t need that. This is what’s bothering me. This is why I’m upset. This is why I cry at nighttime.’ But I didn’t know how to say that.”

West doesn’t say so, but I wonder if the straightforwardness of the diagnosis held the same appeal for him as it did for sports writers. Articles about sports and mental health tend to traffic in a familiar narrative, one in which an athlete struggles in silence with a disorder, then gathers the courage to speak up about it. In the end, we all learn to become more sensitive to those who struggle with a condition that most of us do not have. There can be a lot truth in those stories, and they can serve a valuable purpose. But they can also reinforce the idea that only those with a specific illness need help or support.

Speaking with West on the phone last fall, I mentioned that an increasing number of teams were bringing in psychologists and psychiatrists to work with players. “I guess everybody crazy now, huh?” he quipped. “Maybe I’m not the only one then. Maybe there’s something to that.” Then he turned more serious. “Maybe it’s not a ‘crazy’ thing. Maybe it’s just a highly intense, stressful type of job that puts a lot of pressure on guys to perform and play.” Then there’s the stress that pro sports can put on families and the various outside pressures that athletes deal with. “Guys need somebody to talk to,” West says.

“A Gladiator Background”

Professional athletes face a daunting array of stressors, among them constant travel, irregular sleep, physical injury, and the need to perform impeccably in front of tens of thousands of people multiple times a week. They first face these problems in their late teens and early 20s, what can be a volatile period for many people. And yet all of the psychologists and psychiatrists I spoke to told me that the major pro sports leagues are not doing as much as they could to help athletes deal with these stressors, and that the stigma surrounding mental health remains greater in the sports world than it is in the culture at large—where it is also, of course, considerable.

Athletes tend to be open to discussing mental strategies to aid in performance, often drawing on “mental coaches” and self-help gurus, many of whom are not licensed psychologists. Those conversations can sometimes lead to broader discussions of emotional balance. But “there’s still a stigma about athletes in particular seeking psychological support and guidance,” says Dr. Chris Carr, a sport psychologist who works with the Indiana Pacers. “I think players are more receptive” than they used to be, he says, but “it’s not evolved as quickly as I hoped it would.” Carr has worked in the field for 20 years, and he says the pace of change has been “glacial.”

“You didn’t talk about mental health in the NBA, because we come from a gladiator background,” says Luther Wright, who 20 years ago, as a rookie on the Utah Jazz, was hospitalized after a frightening episode that ended with him “banging on garbage cans” at a rest stop near Salt Lake City. Wright, who has since written a memoir about his dramatic fall and subsequent recovery—he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder but told me his real problem was substance abuse—says the Jazz supported him, but that the league didn’t really know what to do. “At the end of the day, the NBA is a multibillion-dollar business,” Wright says, and nobody had much incentive to help some struggling rookie with serious and bewildering problems. Jason Caffey sensed a similar lack of understanding nearly a decade later. After fleeing a Milwaukee Bucks practice with an anxiety attack and missing the team’s flight to its next game, the Bucks fined Caffey $63,000. The NBA referred him to a psychologist in Milwaukee who was wonderful, he says. But the league’s understanding only went so far: Caffey never got his money back. The general response, Caffey tells me, was, “Jason’s just crazy now because he’s got a lot of kids.” (While in the league, Caffey fathered children with several different women.) He was out of the NBA a year later.

David Stern was the NBA commissioner from 1984 until this January. He told me that attending to the mental well-being of the league’s players, and “treating the whole human being,” was a priority for him, and remains one for his successor, Adam Silver. He also acknowledged that it’s an enormously complicated issue and that there is “more to be done.” The NBA’s player development program is intended to address a range of personal issues, and each team has its own director for that program. These are generally former players, not medical professionals. When it comes to medical care, the league has a network of outside providers that it will refer players to as necessary. While more teams have started to put psychologists and psychiatrists on staff, this is not mandatory. Stern said that if nothing else, teams should understand that providing such care is in their financial best interests—they invest millions in these players, and ensuring that they are mentally and emotionally well makes good business sense. When asked if he thought teams would be wise to employ counselors who met with all their players, since the stresses of the league are considerable for everyone, he said that would be an interesting next step and was “not a terrible idea at all.”

For now, though, the NBA’s approach does not seem as comprehensive as that of Major League Baseball. In a 2010 Sports Illustrated story, Pablo S. Torre traces MLB’s relative success to the establishment of its Employee Assistance Program in 1981. EAPs became more common in the American workplace starting in the 1970s, first addressing substance abuse and later widening in scope. Dr. David McDuff, a team psychiatrist for the Baltimore Orioles for nearly 20 years and part of its EAP, told me that nearly half of the Orioles’ players partake in the program during any given season. The players’ families, too, are welcome to see McDuff and his colleagues, with all charges covered by the team. To get that level of buy-in, he says, team psychologists and psychiatrists need to become familiar faces and spend time with the players on the field and in the trainers’ rooms. Players do come to his office, but McDuff says that conversations also take place “standing in a hallway, standing on a practice field,” or “next to a training table.” He says they eventually come to see him as just another doctor, not unlike the physicians they consult with when they suffer physical injuries.

In the big leagues, what you tell your physician often reaches the public. The NBA’s collective bargaining agreement explicitly grants team doctors permission to disclose “all relevant medical information concerning a player” to the team’s coaches and front office. If the information relates to reasons why a player has not been playing, it may be disclosed to the media as well. According to Dr. Charlie Maher, a sport psychologist who worked with the Cavaliers when West was there—he has also worked with the NFL’s Cleveland Browns and now works exclusively with MLB’s Cleveland Indians—players sometimes won’t discuss their thoughts and emotions because “they’re not sure what’s going to happen with the information.” Maher speaks highly of the front offices that he has worked with in Cleveland, but says that he has heard, both directly and indirectly, of teams being “too loose with the information,” or asking doctors for things that they shouldn’t be asking for, and then implying that “if you don’t give it to me, you won’t have a job here.”

West has had good relationships with the psychologists and psychiatrists that he’s seen and says that he’s been “blessed to be in situations with good ownership and good management.” I asked him about Royce White, who, after he was drafted by the Houston Rockets in 2012, criticized the NBA for lacking any explicit policy related to mental health and insisted that the Rockets address potential complications connected to his anxiety disorder. (White has since played nine total minutes in the NBA, none of them with Houston.) West emphasized that he and White are in “two different boats,” and that NBA teams need not make any new policy for him. He certainly doesn’t want any special treatment.

What concerns West is the stigma attached to players who seek out psychological help. The experience of Major League Baseball suggests that greater openness and more explicit policies can lessen that stigma. In April 2009, MLB sent a memo to all 30 teams detailing the process for putting a player on the disabled list due to mental health concerns. Teams are required to disclose the reason that a player goes on the DL, so privacy in such cases is not really an option. Nevertheless, in the subsequent season, five players went on the DL for emotional reasons, including the next season’s MVP, Joey Votto. Only four players, total, had done so in the previous decade.

A Person Who Plays Basketball

Last October, after his stint in the D-League failed to yield any NBA opportunities, West signed a one-year deal with the Fujian Sturgeons of the Chinese Basketball Association. When the CBA was founded 20 years ago, it seemed like the end of the Earth basketballwise, a desperate destination for fringe players and castoffs. That reputation persists somewhat: The CBA’s biggest star is Stephon Marbury, the rare NBA player who’s been called “crazy” more often than West. But particularly since the 2011 lockout, the CBA has become a landing spot for NBA-caliber players in search of a solid paycheck. The pay is good, reportedly ranging from the high six figures into the low millions for the best foreign-born players, and the league’s shorter season—it lasts from November through February—leaves time to catch on with an NBA team before the playoffs begin back in the U.S.

When I spoke to West on the phone before his first CBA game, he was optimistic. His wife, Caressa—they wed a few days after I first met West in Texas—came with him to China, along with their then-3-month-old son, Cash. Everyone West knows wanted him to name his son Delonte Jr., he says, but he didn’t want his kid “to go to school and get laughed at because of things his father did.” The name Cash, West told me, laughing, echoes “Cassius Clay, Johnny Cash, and his daddy’s jump shot,” which “is money.”

The Sturgeons are based in Jinjiang, a factory city of roughly 2 million on China’s southeast coast. The team put the Wests up in a nice hotel and provided a live-in babysitter. The cities in China reminded West of Manhattan, with “lights, big buildings, and screens everywhere,” and the familiar fast food chains actually served better food: “You’ve never had a Big Mac so good,” he said. The team practiced eight hours a day, and West said he was “doing it with a smile on my face.” In Shanghai, he talked with Yao Ming, who told West he had it easy—his teams used to practice 10 hours a day.

West played well in China, averaging 23 points, six assists, and five rebounds a game. But he’s never been a stat-minded player, and when I met with him after the season, he told me that the Sturgeons had pushed him to score more. (The team had a losing record and fell a couple of games short of the CBA playoffs.) “We need 40 so we can win tonight,” the coaches would tell him, he says. “But that’s a low quality of basketball. That’s open-gym style.” I ask if basketball was still fun over there, and if it’s still fun in general. “Basketball’s always fun,” he says, “but I like to play at the highest level. And that’s why the NBA is where I belong.”

It’s the last day of the NBA’s regular season, and I’ve come to see West at his home in Maryland, about half an hour from D.C. He bought the house in 2008 for just over $1 million, drawn to the lot by the view of the Potomac out back and a farm that sits across the street. On this clear but unseasonably cool April day, several sheep are gathered there. “The World Is Yours” is spelled out in multiple places on the gate surrounding West’s property—a reference to a scene in Scarface, West explains. He has attended to various aspects of the home’s design, doing a fair amount of the work himself, with help from his father and other relatives. Construction is the family business, and the house is West’s main creative outlet these days. He’s wearing a plaid shirt and jeans that are good for working in, and he’s already been to Lowe’s twice that day. When I leave, he’s about to make a third trip.

Photo by Jemal Countess/Getty Images

An NBA team can sign free agents up to the minute its final regular season game begins, so technically there are a few hours of hope left. But the odds of anything happening are remote, and West doesn’t appear to expect a last-minute phone call. In the year that I’ve been following his progress, the New York Knicks seem to have expressed the most consistent interest, but they’re now on the verge of signing Lamar Odom. Odom, a friend and former teammate of West’s on the Mavericks, won two championships with the Knicks’ new president, Phil Jackson. West tells me he’s happy for Odom, who’s seen more than his share of strife. A cousin of Odom’s died—murdered, Odom said—just before that season in Dallas. While Odom was in New York attending the funeral, the driver of a car that Odom hired crashed into a 15-year-old boy, who died of his injuries. Years before, Odom lost a 6-month-old son to SIDS; his mother died when he was 12. A disappointing season with the Mavericks was followed by a very public struggle with drug addiction, and in the gawking that ensued, West sees a failure on the part of fans and journalists to think of Odom as a person, rather than as a Kardashian-affiliated celebrity who’d gone off the rails.

This is a theme that West returns to often. He seems genuinely stunned by the casual cruelty that the Gloria James rumor prompted from all corners of the Web, not to mention people he sees on the street. “That shit affects you. It affects you as a person,” he says. “You go across the world somewhere and somebody says, ‘Is it true, man? Did that really happen? With you and LeBron’s mother?’ And questions like that—that shit crazy, man.” West denies the rumor flatly, and everyone I spoke to who worked for the Cavaliers or covered the team at the time dismissed the gossip.

None of the people I talked to in the league think that the locker room gossip is keeping teams from signing West. There’s also a general consensus that he is still talented enough to help an NBA team.

So what is the issue, exactly? Celtics general manager Danny Ainge told me that the Celtics considered bringing West back during the 2012–2013 season and that if Boston had been a contending team this season—they finished well out of the playoff chase—he would have considered it again. He also said that while West is one of his “favorite guys,” he was “higher maintenance” than he would prefer. Ainge doesn’t think that players get “blackballed,” but he acknowledged that off-the-court issues can follow you around, and teams get scared away from signing certain players. West’s former coach in Boston, Doc Rivers, is now with the Los Angeles Clippers, and West spoke with him when the Clippers came to Dallas late in the season. Rivers was warm and encouraging as always, West says, and he told West that if the team’s injured shooting guard J.J. Redick couldn’t come back from an injury, then perhaps there would be a place for him in L.A. But Redick came back, and the Clippers didn’t make a move.

As for what happened in Dallas, West says that he was unhappy about his contract. He was disappointed that after a solid first season with the Mavericks—he averaged 10 points in 24 minutes per game in 2011–2012, the highest per-minute scoring rate of his career—the team offered him another league-minimum deal. He was apparently vocal about this disappointment, and he was suspended by the team twice in the preseason before getting cut. Reporting on the suspensions was vague, referring only to “locker room incidents” and, of course, mentioning West’s bipolar disorder. The Mavericks, who had several players on one-year contracts, may have felt that West’s complaints would sour team chemistry. In any case, chemistry remained an issue for the team long after West was gone: Well into the season, head coach Rick Carlisle told a reporter he’d had “to literally scream in the face of two guys” for not getting with the program and said he was thinking about suspending players “for not doing things they’re supposed to be doing on the court.” Carlisle would tell me only that he likes West and that “when someone pulls the trigger, they’re going to have a terrific player.” Mark Cuban declined to comment.

A spot in the NBA is not guaranteed to anyone. It’s one of the most difficult jobs in the world to acquire, and it can be just as hard to keep. Every year, 60 more players are drafted, 30 of whom have guaranteed contracts. West says that all he wants is for another team to give him a shot, and he doesn’t understand why that hasn’t happened. He says he has no contract demands. Whatever bitterness he may have felt about becoming a league-minimum player after the arrest is gone, replaced by a wish that his wife and son will get to watch him play in the NBA.

Sports writers are very familiar with tidy narratives: wins and losses, good guys and bad guys. West’s story is more complicated than that. It seems clear that he can still play at an NBA level, and to my untrained eye, he appears to be doing well both personally and emotionally. It also seems obvious that cruel media coverage has hampered West’s career—that the constant mentions of and questions about his diagnosis and his arrest could make some front offices less inclined to sign him to a contract.

Photo by Ronald Martinez/Getty Images

At the same time, West has occasionally made life difficult for teams that he’s played for. He is a good player who has always performed well. He is not a star. Partly because he has the mindset of a facilitator, and partly because he doesn’t have the physical gifts of a Michael Jordan or a LeBron James, he does not put up the kind of numbers that would force a team to take a chance on him. “Whatever the challenges may be,” Danny Ainge told me, “the better the player, the more you can put up with, for sure.”

I don’t know whether this story will have a happy ending, or what that happy ending would even look like. The 30-year-old West believes he can play at an NBA level for another eight to 10 years, and, in theory, that’s not out of the question—he’s a cerebral player who doesn’t rely on the sort of athleticism that starts to fade in a basketball player’s mid-30s. Realistically, it will become harder and harder for West to re-enter the league the longer he’s out of it. Perhaps the happy ending here is that West will continue to play overseas, staying out of the harsh NBA spotlight, providing for his growing family and redesigning his home.

Though he is clearly disappointed and confused by the lack of interest from NBA teams, West seems to be in good spirits now. He told me he no longer takes medication, but he stays in touch with Dr. Eppright in Cleveland and is surrounded by family and friends in Prince George’s County. He believes he’s matured a great deal in the last few years, especially since meeting his wife and becoming a father. West is Christian, and he referred often to the idea of the “via dolorosa,” the sorrowful way that Jesus walked, showing his followers how much pain they can bear with God’s help. West, who has several tattoos of his own design, has the phrase written across his chest.

He quit Twitter a year ago, knowing that it had hurt his public image, and he retired his “rap career,” he tells me with a laugh, referring to a little sideline that he worries may have convinced some teams that he was not entirely focused on basketball. “There’s nothing more that I can accomplish in my rap career,” he jokes. “I’ve done it all.” He went back to his original agent, who first represented him out of college, convinced that the misunderstandings about his D-League stint could have been avoided. But he says he wouldn’t change the Dallas experience, because that’s where he met his wife, and now the two of them have a son, and West calls this his greatest accomplishment. He and his wife are now expecting again, soon to find out whether they’ll be having a boy or a girl.

As for what he has “accomplished sportswise,” West has mixed feelings. In his basement, there’s a row of framed jerseys and some shelves with trophies and other memorabilia: a plaque from his recent induction into the St. Joseph’s Basketball Hall of Fame, some framed news stories, a photo of him throwing out the first pitch at Fenway Park. West put up the shelves just the day before, and the jerseys, which were framed by his mother, a week prior to that. He says it’s the first time he’s ever hung up mementoes from his basketball career. “I’ve been so disappointed in myself, I didn’t want to see anything,” he says. “I couldn’t even embrace the accomplishments.” Hanging them seems like progress, but West isn’t so sure. “I might take that down, because I don’t want to put no jerseys up,” he says. “I’m not retired. This is what I did? I’m still doing it.”