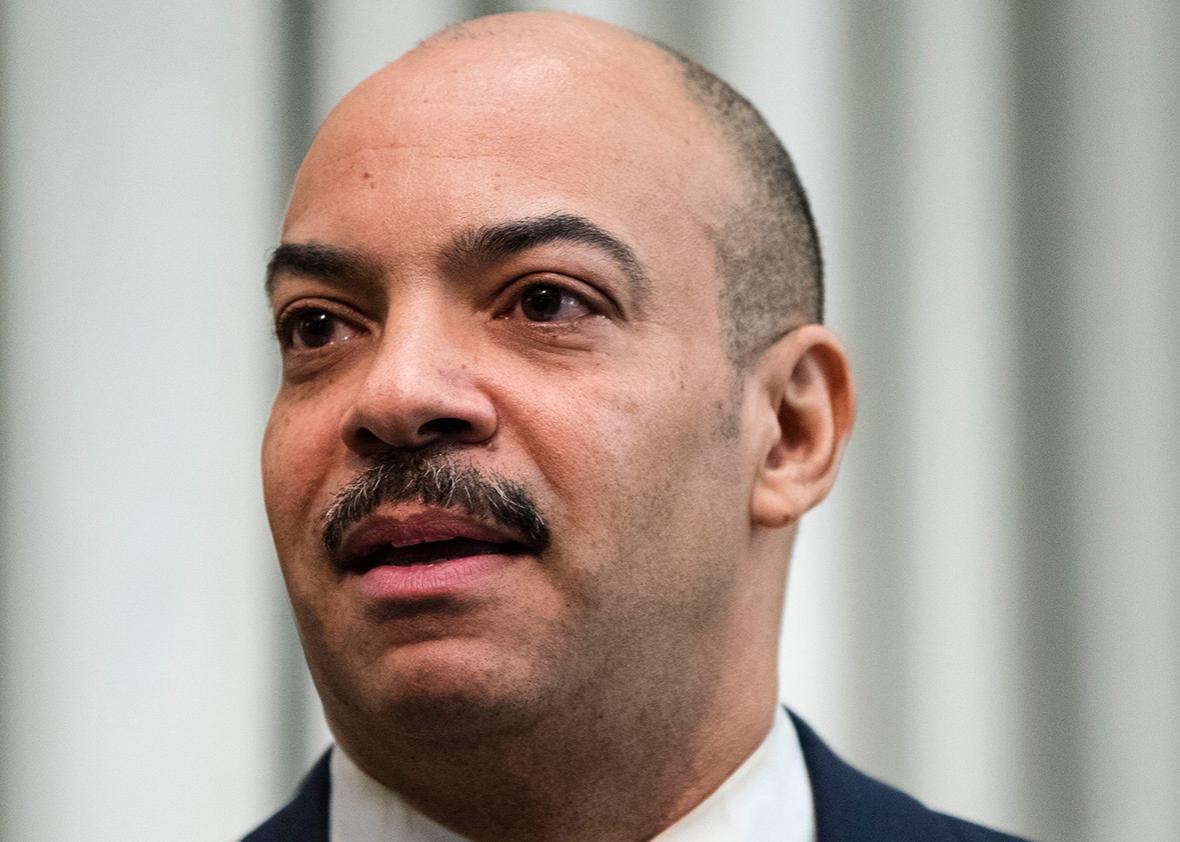

On a Friday morning in early February, Philadelphia District Attorney R. Seth Williams gestured the local press closer, opened a folder, and let out a loud sigh. “After devoting over 20 years of service to the city that I love and grew up in,” Williams said at a press conference, reading from a prepared statement, “I have made the very difficult decision not to seek re-election to a third term as the district attorney of the city of Philadelphia.” Williams usually has a politician’s voice, personable and sonorous, but on this morning his words kept catching in his throat. More than one reporter described the tears in his eyes.

At the time, the moment may not have seemed particularly notable. If not for the passing allusions to the “embarrassment and shame” he felt about the “regrettable mistakes” in his “personal life and personal financial life,” it would have seemed as if Williams had accomplished what most politicians hope for: the chance to leave office on his own terms. The truth, though, is that large portions of Williams’ legacy will now be a matter for the courts to decide.

On Tuesday, the Philadelphia DA was federally indicted on 23 counts of bribery, extortion, and fraud.* The charges were announced by federal law enforcement officials from the Department of Justice, the FBI, the IRS’s criminal investigation division, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s homeland security investigations division. An FBI special agent called his alleged misconduct “brazen and wide-ranging, as is the idea that a district attorney would so cavalierly trade on elected office for financial gain.”

Williams has already been in trouble over his sloppy record-keeping: In January, he was forced to pay the largest fine in the history of the Philadelphia Board of Ethics after he failed to disclose almost $200,000 worth of gifts and expenses. But if the federal charges are correct, Williams’ misconduct went much further. According to authorities, Williams not only accepted 16 round-trip plane tickets, vacations, a car, a sofa, and countless other gifts, but he traded those gifts for favors, including lighter sentences from his office.

If these allegations are true, Williams has violated the public trust in a significant way. But this is only the most recent in a long litany of disappointing behavior by Williams, who has always been better at talking about justice than he has been at practicing it. Over the past seven years, he has tried to look the part of the bombastic, idealistic outsider fighting for justice. He has behaved instead like a timorous yet power-hungry insider fighting for no one. He has either valued the wrong principles or none at all, and poor people and communities of color have had to pay.

Williams, a Democrat, was first elected as district attorney in 2009, beating the Republican opposition with 75 percent of the vote. Earnest and intelligent in conversation, Williams is hard to dislike, and voters appreciated the struggles he’d faced in his past: As a baby, he was put into foster care and was eventually adopted. His election also reflected the dramatic demographic shift in the city, which lost almost one-third of its white residents between 1990 and 2010.

As a candidate, Williams won by painting himself as the reasonable reformer, a contrast to his defiant and defensive predecessor. It wasn’t difficult to be more of a reformer than Lynne Abraham, the woman known as the “Queen of Death” because of the 108 death-penalty convictions her office secured in her 19 years as DA. Last year, the Fair Punishment Project named Abraham one of America’s five deadliest prosecutors.

Williams, on the other hand, employed kinder rhetoric on the campaign trail. “Mr. Williams repeats practiced lines from a justice-reform movement that has taken hold in places like New York, San Diego and San Francisco,” wrote the New York Times in 2010. The article quoted Williams spouting out vague reformer-tinged language, like “Crime prevention is more important than crime prosecution” and “We need to be smarter on crime instead of just talking tough.” He called for some specific progressive policies, such as restorative justice programming and an end to prison overcrowding.

But most of that rhetoric turned out to be empty talk. Today, Philadelphia’s jail incarceration rate is higher than anywhere else in the country and more than three times the national average. A recent study found that Williams’ office detains 1 in 4 misdemeanor defendants simply because they can’t afford bail.

Williams has not only punished the poor for being poor, but he’s stolen from the innocent. Asset forfeiture abuse by law enforcement in Philadelphia is rampant. A 2015 American Civil Liberties Union report found that police and prosecutors have taken more than $1 million in cash from 1,500 people who have not been convicted of a crime—71 percent of whom are black. The city has pulled in around $5 million annually from confiscating the property of constituents, and more than $2 million of that goes directly to the district attorney’s office.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Williams has often failed to hold corrupt police and prosecutors accountable. He defended blatant misconduct, refusing to fire multiple prosecutors that were caught exchanging pornographic, misogynistic, and racist emails. And more than once, he has continued to use a police officer as a witness despite the fact he has been caught lying on the stand.

Williams has also failed reformers on the same issue that defined his predecessor’s tenure. After Gov. Tom Wolf was sworn into office in 2015, he implemented a death-penalty moratorium, calling on a state task force to do further research. Mother Jones reported that “Wolf listed race discrimination, bad lawyering, high costs, and the threat of executing an innocent man among the reasons for his decision.” The Pennsylvania governor called capital punishment “a flawed system that has been proven to be an endless cycle of court proceedings as well as ineffective, unjust and expensive.” Endless cycle was correct: At that point, it had been almost 16 years since the state had executed someone. The data also supported Wolf’s claims of racial injustice—in 2007, a report sponsored by the American Bar Association found that one-third of the black people on death row in Pennsylvania would probably not have been sentenced to die had they not been black.

Given all those factors, Wolf’s temporary stay on executions seemed like a reasonable request. Seth Williams apparently didn’t think so. Instead, the Philadelphia DA—a self-proclaimed reformer, the first black elected prosecutor in the entire state, and the chief law enforcement officer of the county with the highest black population in the state—decided to fight Wolf’s temporary moratorium, calling it “flagrantly unconstitutional.” The state Supreme Court did not agree with that assessment, ultimately ruling in favor of Wolf.

While Seth Williams has not been as dedicated to the death penalty as his predecessor, his office has still sought a greater number of death sentences than more than 98 percent of prosecutors across the country. Among the people he wanted to execute was Terry Williams, who was a teenager when he killed his two rapists, middle-aged men who had been sexually abusing him for years. Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Williams v. Pennsylvania that Terry Williams’ due process rights had been impermissibly violated, entitling him to a new sentencing hearing.

Seth Williams did implement some legitimate reforms as district attorney, including supporting alternatives to incarceration for some people charged with low-level offenses. He also has a habit of making promises only to renege after the initial wave of good press has died down.

In 2016, for instance, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Montgomery v. Louisiana that inmates serving mandatory sentences of life without parole for crimes they committed as juveniles were entitled to resentencing. Technically, prosecutors had the option of recommending a life-without-parole sentence again, but those sentences would only be appropriate for “those rare children whose crimes reflect irreparable corruption.”

At the time, almost 300 inmates in Williams’ jurisdiction were entitled to resentencing—more than anywhere else in the nation. As these new hearings approached, advocates and reformers from across the nation called on Williams to agree not to request life without parole for any of those 300 people. When he stated on Twitter in 2016 that he would offer the possibility of parole in each case, I publicly lauded him for his bravery, and Williams thanked me. But just a few weeks ago, the DA backtracked, claiming he had never agreed to not ask for life without parole.

Had Williams believed that one of the many articles lauding him for his decision had misrepresented his position, it seems he would have clarified. But perhaps the good press was too good to pass up.

Just seven years ago, Williams seemed poised for political fame, destined to become a star of the Democratic Party. But at the podium last month, he looked like a man defeated. Williams has always been good at sounding good, but he has repeatedly failed to answer the call to do what’s right. Williams abused the public trust in multiple ways during his tenure as district attorney. In the end, it turned out his reform jargon was mostly for show.

*Correction, March 23, 2017: This piece originally misidentified Seth Williams as the former Philadelphia district attorney. He is still the Philadelphia DA. (Return.)