Predicting the result of any Supreme Court case is a fool’s errand—but let me play the fool for a moment and make a prediction: By the end of this term, Florida’s malicious, muddled, singularly screwed-up death penalty sentencing system will be no more.

That conclusion appeared all but unavoidable after oral arguments on Tuesday in Hurst v. Florida, a capital sentencing case whose complex problems all point toward a simple solution. For a surprisingly entertaining hour, the justices returned to the death penalty after a brief reprieve. Only this time, instead of a bickering brawl, the justices engaged in a thoughtful debate that might actually bring sorely needed justice to some death row inmates.

Hurst is a simple case about who gets to decide whether a defendant will live or die. Under current Supreme Court jurisprudence, a capital defendant may present to the jury “mitigating circumstances”—factors, such as childhood trauma, which diminish his culpability. Prosecutors, however, may present to the jury “aggravating circumstances”—factors, such as extreme depravity or premeditation, which increase the defendant’s culpability. Typically, the jury decides whether these aggravators were proved beyond a reasonable doubt, and whether they outweigh mitigators. If so, the jury sentences the defendant to death. If not, the jury spares his life.

Florida follows this constitutionally mandated system—with two perverse twists. First, while a jury of 12 does assess aggravators and mitigators, it doesn’t have to decide unanimously whether aggravators outweigh mitigators. In fact, it doesn’t have to decide anything unanimously during sentencing. So long as just seven jurors believe an aggravator justifies the death penalty, the jury must recommend that the defendant be executed. Even if each of the seven jurors cites a different aggravator, the jury as a whole must endorse execution. And the defendant is barred by state law from asking the jury to explain which aggravators justified capital punishment.

The second twist is similarly bizarre. Although the jury recommends a sentence to the judge, she is under no obligation to follow it: The jury’s decision is, by law, “advisory.” That means judges can actually override a jury’s recommendation of life in prison and condemn a defendant to death instead. And yes, Florida judges have done exactly that. It also means that the judge can impose death based on aggravators that the jury found irrelevant or unproven. And if the jury can’t reach a decision? Under Florida law, that’s no problem: The judge can simply impose death on her own. (The only other state to give judges so much power over life and death is Alabama, where judges routinely override jury recommendations for life in prison and impose capital punishment instead.)

Florida’s sentencing scheme presents a serious constitutional conundrum. The Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial requires that, in death penalty cases, all aggravators be proved to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt. But in Florida, a judge can rely on aggravators that were not proved to a jury. She can even rely on aggravators a jury never considered. Moreover, several justices have found that the Eighth Amendment’s bar against “cruel and unusual punishments” requires a jury, not a judge, to impose the death penalty. Juries, these justices believe, reflect the community’s “moral sensibility” and “considered judgment,” which the Constitution requires in any death sentence. A jury’s decision represents the wishes of at least a fraction of the defendant’s peers. A judge’s decision might represent nothing more than her empty stomach.

At the top of the hour, all eyes are on the unusually engaged Scalia, a wild card in jury trial cases. Scalia may not care about sparing death row inmates—this is, after all, the man who thinks executing the innocent is perfectly constitutional—but he’s obsessed with the right to a jury trial. In 2002, he even agreed (hesitantly) that capital defendants have a constitutional right to put aggravators before the jury.

But that was a long time ago, years before Scalia became the Fox News justice. As soon as Scalia opens his mouth on Tuesday, it seems his vote is going to Florida.

“This necessity of finding an aggravating factor, we made it up, right?” Scalia asks Seth Waxman, the former solicitor general who is arguing against the Florida law. You can almost see Waxman bid adieu to Scalia’s vote. Soon after, Scalia continues: Florida’s laws “require unanimity for a conviction, right? They just don’t require unanimity on the sentence.”

Scalia’s point here is that the whole system of aggravators and mitigators was largely imposed on states by the Supreme Court to keep them from executing inmates willy-nilly. Since Scalia tends to err on the side of willy-nilly executions, he doesn’t like the system, and isn’t eager to strike down Florida’s workaround.

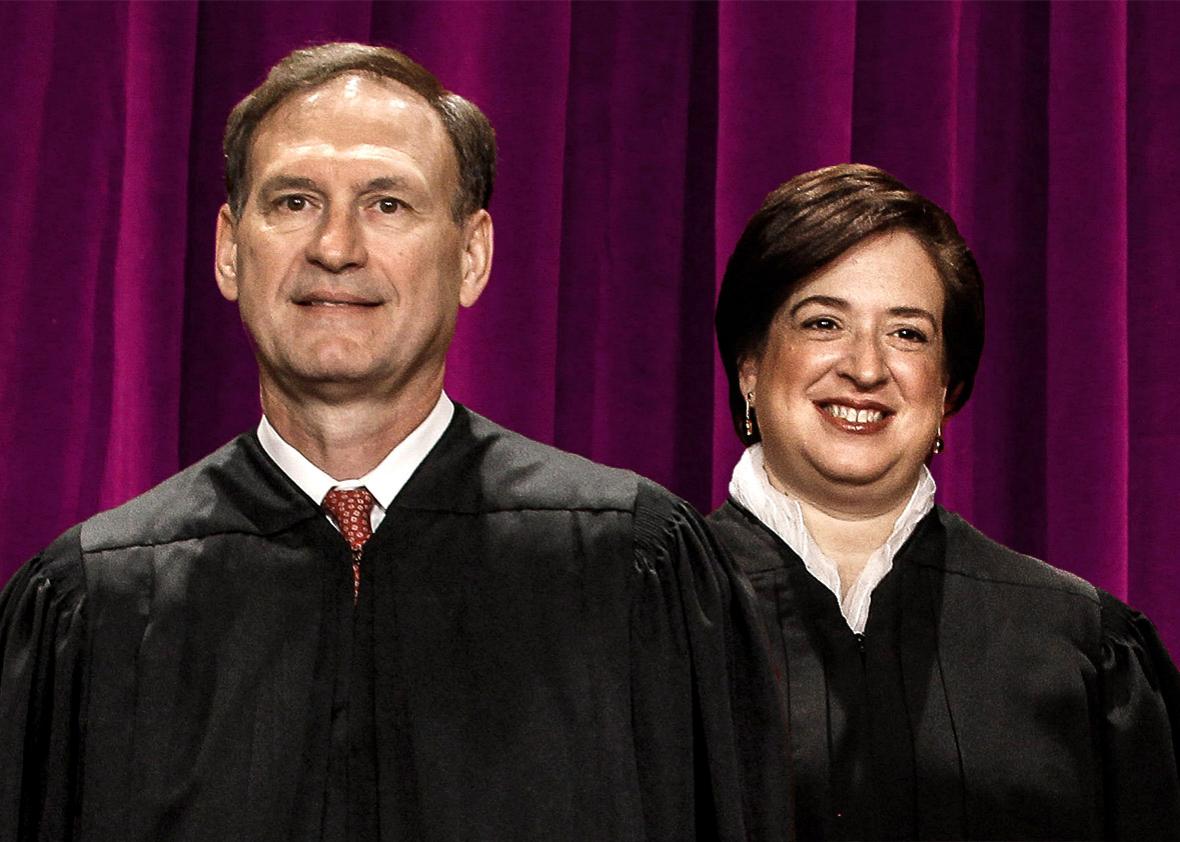

Justice Elena Kagan jumps in to help Waxman, unspooling a Breyer-esque hypothetical designed to demonstrate why a merely advisory jury verdict would violate the Sixth Amendment. Justice Samuel Alito—who spends much of the morning leaning way back in his chair, eyes closed, lips pursed—abruptly sits forward and strikes.

What if, Alito asks, the jury is told that “if you decide on death, the judge is going to review it, and the judge has the power to sentence to life” instead?

This is an obvious question with an obvious answer—a disappointing performance for the typically trenchant Alito.

“Our view,” Waxman responds smoothly, is that under the Eighth Amendment, “capital sentencing has been, and as a matter of constitutional law should be, done by a jury.” A judge can choose to spare a defendant’s life in contravention to a jury’s verdict—and indeed, in some states, they do (albeit rarely). But the Eighth Amendment prevents a judge from sentencing a defendant to death when the jury votes for life. Alito’s point effectively defanged, Waxman returns to his seat triumphant.

Allen Winsor, the Florida solicitor general who has the unenviable task of defending his state’s indefensible law, doesn’t fare quite so well. Justice Stephen Breyer, the court’s leading death penalty skeptic, pummels Winsor with questions meant to show that a judge can impose death when a jury wants life under Florida’s law. Winsor evades the question for a few painful minutes before Breyer demands a real answer.

“My simple question is,” the justice declares, “as a matter of Florida law, can the judge impose the death sentence? Yes or no.”

“As a matter of Florida statutory law, yes,” Winsor responds—but as a matter of constitutional law, “no.” There is a moment of silence as everybody realizes that Winsor just gave away his case, openly admitting that Florida’s capital sentencing laws are incompatible with the Constitution. Breyer relents, but spends the rest of the morning looking frustrated, gazing at the audience like a captain looking out over a foggy sea.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, the probable swing vote here and possibly for all eternity, remains conspicuously silent throughout the morning, appearing listless and bored. So everyone’s head snaps up when he asks his first question.

“You’re saying that it is possible,” Kennedy proceeds cautiously “that under Florida law, the jury would not find the existence of an aggravating factor,” but “the judge could then proceed to find an aggravating factor and impose the death penalty?”

Winsor tries to stammer out a response, but Kennedy continues.

“Now, you say this hasn’t happened. He’d probably be reversed. But theoretically this could happen?”

Predictably, Winsor dodges Kennedy’s question, swerving toward some amusing banter with Kagan. But Kennedy brings it up again, sternly advising Winsor that “a death case is not funny.” Winsor’s stammering response makes no sense, and Kennedy’s face veers from stultified to pissed off. You don’t sidestep a question from the most powerful man in America.

Arguments close with a rousing, largely uninterrupted rebuttal by Waxman, then the justices file slowly off the bench. As they amble toward the robing room, the resonant sound of Justice Clarence Thomas’ laughter echoes into the courtroom. He’s chatting with Breyer, and the two are all smiles and camaraderie. One of them will likely lose this case, but at that moment, it didn’t seem to matter. Meanwhile, 394 people sit on Florida’s death row, many of whom may have been sentenced unconstitutionally. For them, the outcome of Hurst could be the difference between life and death. But the specter of the execution chamber is far away from the court as the justices head to lunch. Thomas’ laughter fades, and we all exit the courtroom into the sunny fall afternoon, putting images of gurneys and needles out of our minds as we stroll down the blindingly white marble steps.