This article is part of the Big Shortcut, an eight-part series exploring the exponential rise in online learning for high school students who have failed traditional classes. See the whole series here.

Every time a salesman for an online learning company pitches a school district, he promises its educational software is “engaging.” But, of course, they can’t all be. The programs that schools use to help their students make up lost academic credits run a massive gamut in quality: The best incorporate compelling videos, varied assignments, and ample opportunities for teacher-student interaction. The worst feature boring, outdated lectures from dispirited-looking instructors, and endless multiple-choice questions. Some schools use the staler options as a supplement to traditional teaching, while others rely on them to entirely supplant in-person instruction. Here is a shortlist of online credit recovery products that raised our eyebrows—well, until we fell asleep.

Odysseyware

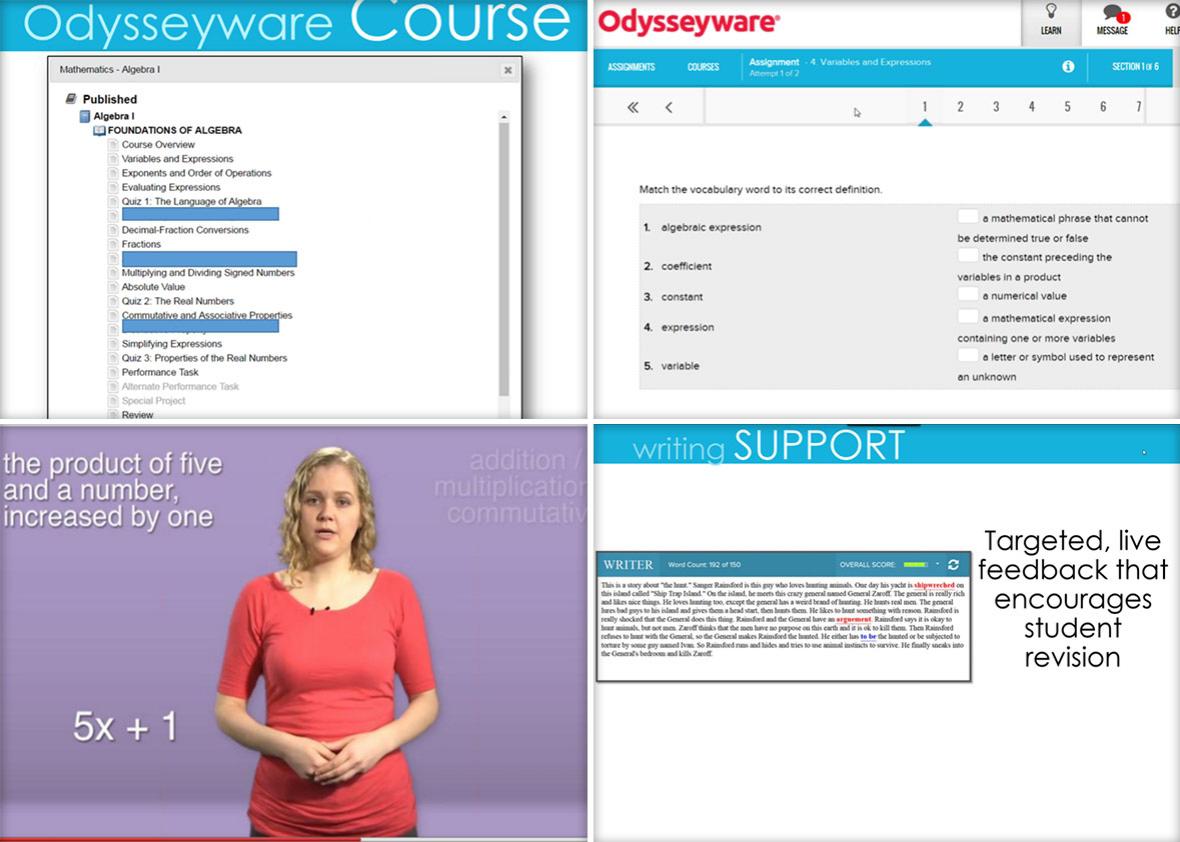

Odysseyware: Unlike many educational software companies, Odysseyware focuses primarily on online credit recovery. Eighty percent of the company’s customers deploy the programs for students that need to make up courses, according to Odysseyware consultant Misty Blackmon.

Blackmon actually touts the speed at which kids can fly through Odysseyware coursework: Each unit starts with a pretest, and schools can decide what percent of questions their students need to answer correctly in order to pass. (The National Collegiate Athletic Association, for one, generally frowns on this practice.) Even if a student fails an Odysseyware pretest, he only has to redo the lessons corresponding with the questions that he failed rather than the entire unit. He can retry tests and quizzes as many times as the school deems fit. And the questions remain identical each time students take the tests—making them easy to memorize and pass on subsequent tries.

Odysseyware lessons include two- to three-minute video lectures of teachers standing in front of green screens; the style vaguely resembles in-flight safety presentations. Students are graded based on simple exercises, like matching words with their meaning, and multiple-choice questions. Written response questions are graded by the computer based on grammar, spelling, word count, and topic agreement—not necessarily by the teacher, although instructors do have that option. “We don’t pretend to think that a teacher would be able to go back and look at” them all, Blackmon says. In other words, Odysseyware counts on minimal effort at times—not only from the students who use its programs but also from teachers.

Edmentum

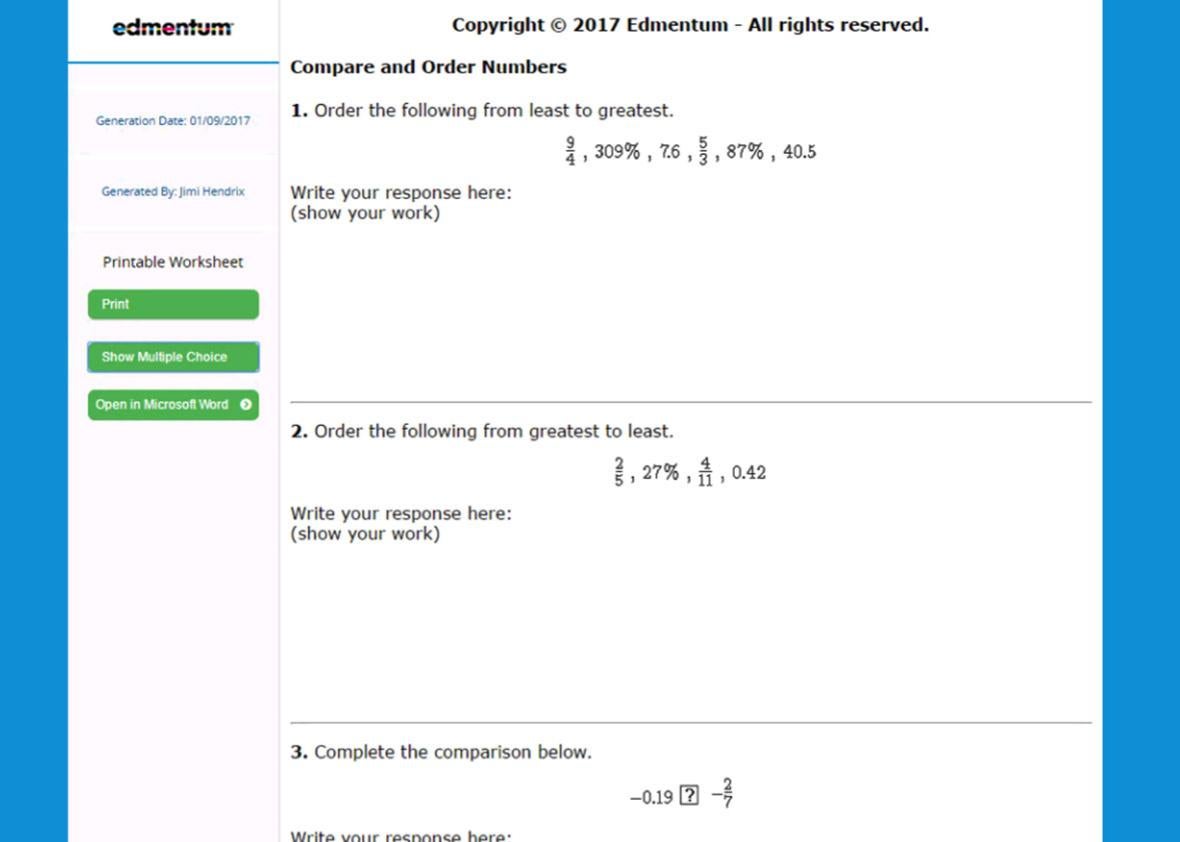

Study Island: Created by edtech giant Edmentum, this study tool for students isn’t intended to be used for online credit recovery, although it occasionally is anyway, according to David Cicero, a sales specialist with the company. It’s lacking the depth of material needed for students to learn an entire class’s worth of content, he says. Cicero recommends that schools instead use another Edmentum product, Plato Courseware, for making up courses.

Study Island basically consists of a series of computerized worksheets—solving endless algebraic equations, for instance—with very little interactive instruction. (There are a few Khan Academy videos sprinkled throughout.) By contrast, Plato Courseware features animated videos, documentary clips, and interactive activities. But Study Island is cheaper, which could be the reason so many districts choose the less sophisticated product. “[Plato] might be out of a school’s budget,” Cicero says. But both Cicero and Edmentum’s marketing director declined to say how much either program costs.

A Beka Academy

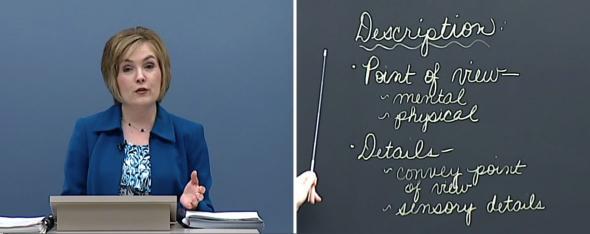

A Beka Academy: An affiliate of Florida’s Pensacola Christian College, A Beka Academy serves two primary markets: homeschoolers and students in Christian schools. Some online learning providers give customers an interactive experience; others are more isolating. But A Beka’s trite broadcasts are in a league of their own (the company improved its web design this spring, but most of the sample videos detailed below remain available for viewing).

One rambling four-minute excerpt from an 11th-grade English course, for instance, consists mostly of corny lectures from a teacher on the work of 17th-century poet Anne Bradstreet. “[She] calls her poetry a child,” the teacher says. “And just as a child can be unruly, just as a child may not quite always look just right … this morning as we’re eating breakfast, I look at the girls, and they’ve got Nutella all over their face,” she continues. Poetry, like children, can be “a little messy.” The instructor wraps up by questioning the students about the religious message of Bradstreet’s poetry. The students then take turns rising, accepting a microphone, and slowly reading their handwritten responses in flat tones—not exactly engaging pedagogy that’s likely to hold the interest of struggling learners.

In another sample, a 12th-grade class called “Document Processing,” students can learn typing while watching four videotaped teenagers, well, type. The teacher circulates between the teens on the video, reminding them to “add that space there” and providing other tips. By the time she asks the students to check their posture, the viewer himself may be so bored he’s slouching out of his chair.

Video classes in Spanish and family consumer science are a bit more interactive. In the former, a teacher asks her students to repeat and interpret the religious meaning of biblical verse: Porque ninguno de nosotros vive para sí, y ninguno muere para sí. (“For none of us lives for himself, and no one dies for himself” —Romans 14:7.) They discuss it in English; the implicit aim of the class is deriving existential significance from the sentence, not practicing the Spanish language. In the second part of the sample video, the teacher asks students to join her in a Spanish gospel sing-along. The consumer science class, meanwhile, looks like a low-budget cooking show: A woman stands behind the island in an empty kitchen explaining how to save money—and reduce fat—while making buttermilk biscuits. One wonders how, in the age of endless YouTube content, a video like this will hold kids’ attention—or why school officials even allow these teaching tools into the classroom at all.