WILLINGBORO, N.J.—“This is your health care bill,” one of the more polite constituents told his congressman, New Jersey Rep. Tom MacArthur, during a long, hostile, passionate, and often unbearably nasty town hall Wednesday night. “It was dead in the water and could have stayed dead in the water. It was done.”

“This is your amendment, sir,” the man continued. He has a heart condition, and is worried about what would happen if he loses his job, has a gap in his coverage, and can’t afford insurance on the individual market. “Because of that MacArthur amendment, you brought it back from the dead, with that amendment.”

“It’s yours,” he said. “You own it.”

If Tom MacArthur didn’t know that he owned the American Health Care Act before this town hall, he knows it now.

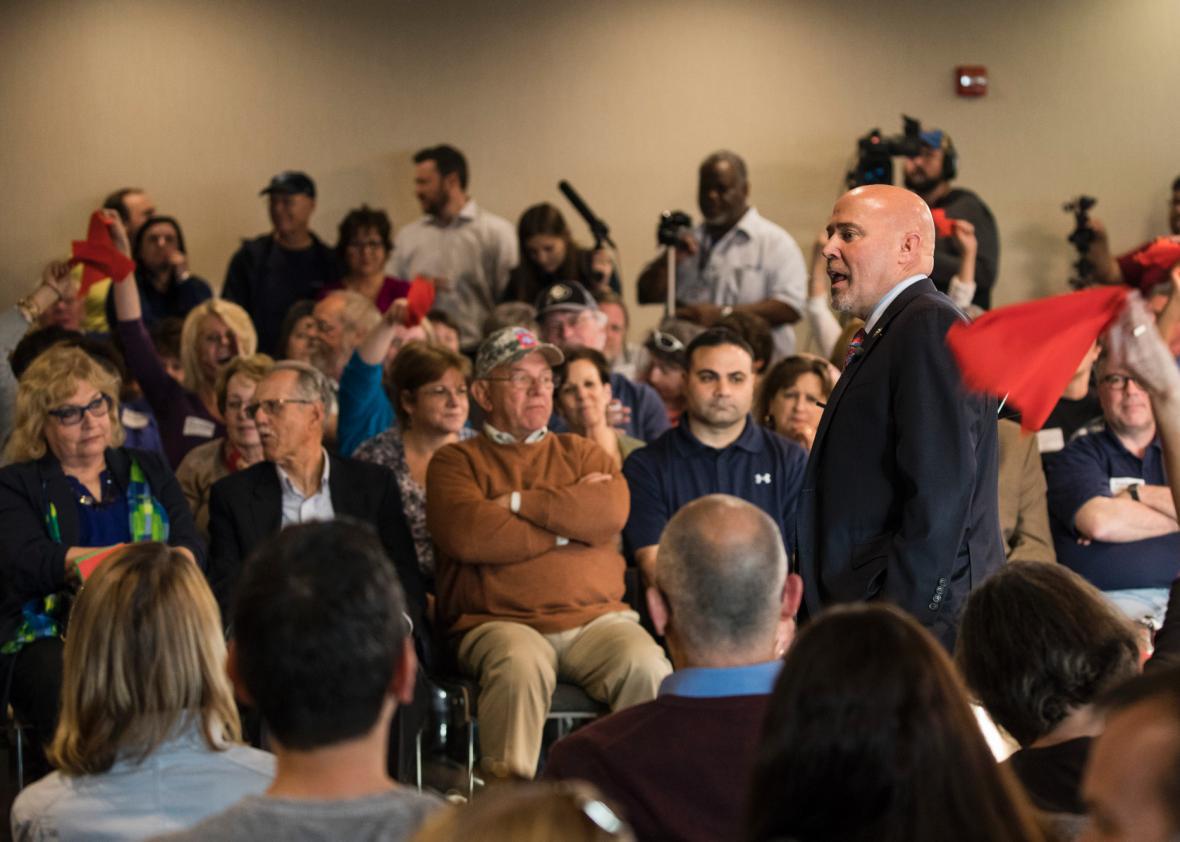

For more than four hours, MacArthur, author of the amendment that revived the GOP health care bill after its original flameout in March, fielded a mix of questions, impassioned monologues, and insults from constituents in Willingboro, a town in South Jersey where only 12 percent of voters supported him in the most recent election. Zero people in the room seemed likely to support him in the next one. Only one person described herself as a Republican, and she was not happy with the AHCA.

The room was filled to capacity, with about 200 to 250 people in chairs surrounding MacArthur. About twice that many people waited in line but couldn’t get in, and that’s not counting the protesters. (Or the media. Just about every Washington reporter not writing about James Comey showed up.) The streets of surrounding the Willingboro rec center were lined with parked cars. Residents came outside to see what was going on. One, standing by her stoop, looked up at the helicopters swirling above her house with binoculars.

MacArthur made an awkward entrance to a barely audible Coldplay song, smiling and shaking hands along the way to those who didn’t appear interested in smiling or shaking. The mild-mannered, second-term congressman is still not quite comfortable being a political celebrity. But that’s what he made himself when he, as a co-chairman of the moderate Tuesday Group, went out on a limb and negotiated an amendment with the Freedom Caucus to give states waivers for certain Obamacare regulations. Once that amendment was agreed to, leaders just had to squeeze a few moderates to get the AHCA over the line.

The nastiest moment of the night came before MacArthur even took questions. The congressman began to tell the story about his daughter, who was born with a disability and died when she was 11 years old. Some members of the crowd appeared familiar with the story and didn’t want to hear it again, suspecting it was a play for sympathy.

“Shame on you!” someone said.

“Well, I’d say shame on you,” MacArthur said back, calmly.

“I’m very pleased you have a nice story,” another said, before urging him to move on to the topic at hand.

“Were you able to afford her health bills?” yet another said.

MacArthur urged everyone to stay civil, that there would be plenty of time to discuss the AHCA. This just caused more bickering. One constituent shouted about another, “she’s over here talking and bitching, tell her to shut up!” Soon everyone was telling everyone else to shut up.

Eventually, the questions began.

Dominick Reuter/AFP/Getty Images

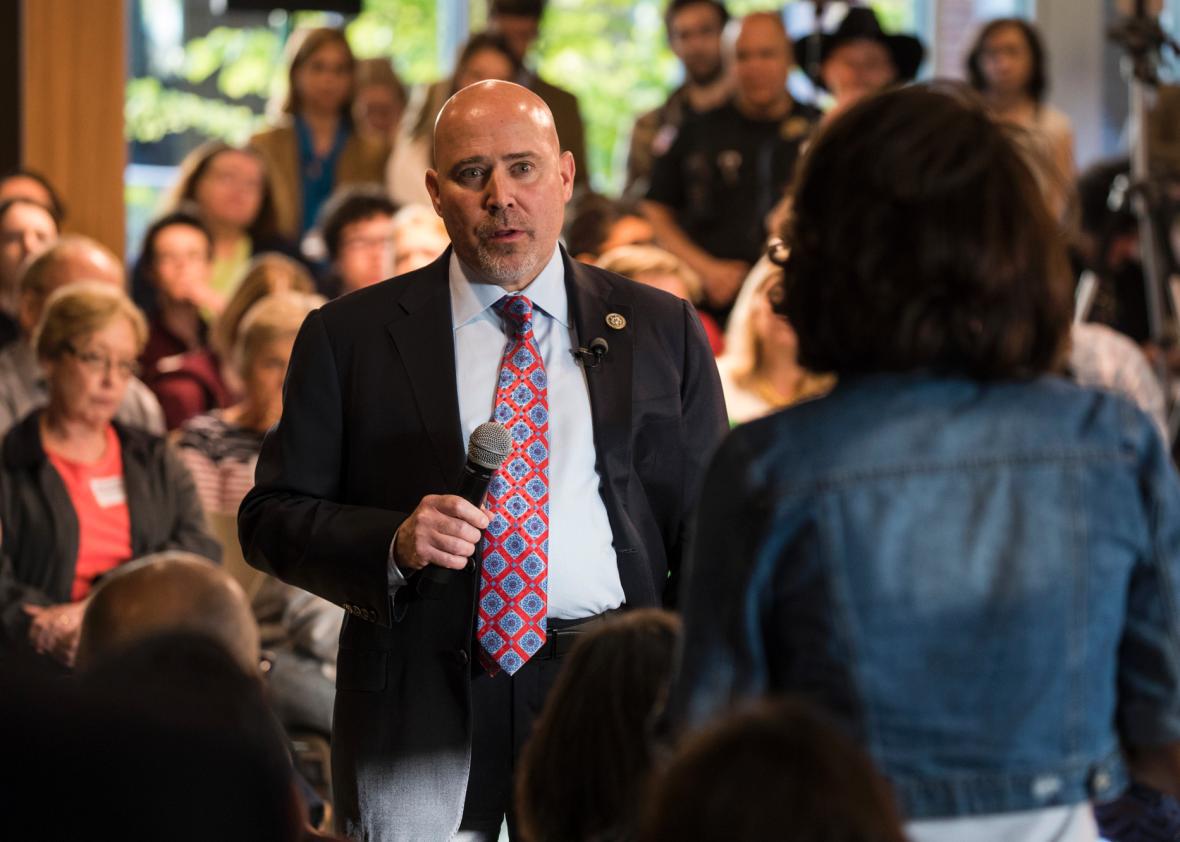

MacArthur fielded many fair, brutal questions throughout the night, between the insults or extended speeches. (Some residents came prepared with elaborate statements, noting the many cameras in the room.) Most of the questions, appropriately, were about health care, with a healthy dose of Russia thrown in the mix. MacArthur didn’t have much to say about President Trump’s firing of FBI Director James Comey, instead just saying that he hoped the House and Senate intelligence committees could resolve their investigations soon. When asked whether it was time for a special prosecutor, he said, “No, not yet,” to a chorus of boos. But it was a health care night.

One constituent explained how his wife had died two months earlier from brain cancer, and how he was taking his kids on vacation for Mother’s Day. He worked in insurance. “The Affordable Care Act has plenty of flaws,” he said. “The problem is this bill has a lot more flaws.”

A recovering addict told him that Medicaid was what “kept me clean this long.” Without it, she said, “it’s jail, institution, or death.” He told her, and anyone else asking about Medicaid, that no benefits would be cut, and that the bill’s $839 billion in cuts would simply force states to bring about efficiencies and innovation. (Some of those efficiencies that the states could settle on, of course, would be slashed benefits.)

One man, whose wife is a cancer survivor and whose two children each have pre-existing conditions, engaged in a long, furious rant that lasted about 15 minutes. “You are the greatest threat to my life,” he shouted. “You are what keeps me awake at night.”

“We’ve met before,” one woman, who had a question about single-payer health care, said, introducing herself. “I gave you a hard time before, too. I must say I have a great deal of admiration for your tolerance for masochism.”

MacArthur—who said at the outset that he would take questions “as long as it goes,” his biggest mistake of the night—assured her that he did not enjoy this.

MacArthur didn’t spin the effects of the MacArthur amendment as brazenly as some members have done in selling the bill. He didn’t say that no one with pre-existing conditions would ever be pushed out of commercial markets. He just laid out his rationale in drafting the MacArthur amendment: The way to fix the problems with individual insurance markets, he said, was to place those with expensive pre-existing conditions in taxpayer-funded high-risk pools to allow premiums for the rest of the market to come down. The attendees could take it or leave it. They left it.

Dominick Reuter/AFP/Getty Images

Only once during the questions did he seem close to losing his temper. It was not when the room broke out in a rendition of “na na na na, hey hey hey, goodbye,” right after he had said that he thought it was rude of the House Democrats to sing that on the House floor. It was not when someone called him “Tommy Boy” in the middle of a rant, after describing the AHCA as a “huge pile of excrement.” There were many times when another politician in this situation would have lost his temper, repeatedly. The governor of his state, many of whose town halls I’ve witnessed, would have been flinging D batteries at his constituents after about 10 seconds of this treatment.

It was just one time, about midway through, when someone in the back called him an “idiot.” He stopped himself from taking another question, asking what sort of person would call “your congressman” an “idiot.”

“I really wonder how any of you would perform in Congress with that attitude,” he said, sharply.

Shortly after that came the guy with the 15-minute speech, the one who had called his congressman “Tommy Boy.” It was around the middle of this guy’s lecture that MacArthur’s staff seemed to fully develop the maybe this wasn’t the best idea? look, and when the police moved closer to MacArthur from outside the perimeter.

“Folks, I’m going to answer two more questions,” he said after the speech, which he did not respond to. “I think we’re at this point. This is not just going to turn into a free for all, which it is now.”

He then took several more questions, and they became much more civil. Even this room, at some point, had to exhaust its energy.