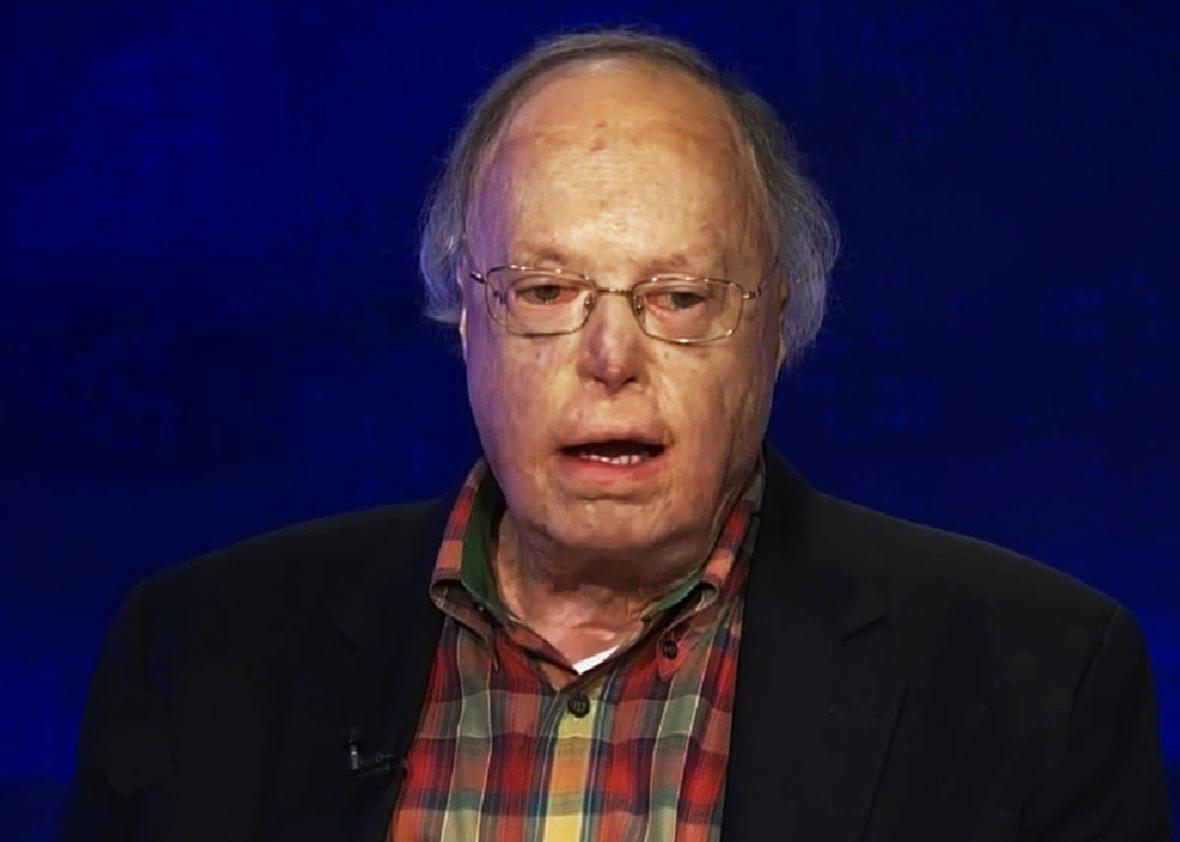

Robert “Bob” Timberg’s funeral was Sunday in Annapolis. He was 76 and the bravest man I knew.

The night before I met Timberg in 2011, I flipped through my father’s 1964 copy of Lucky Bag, the United States Naval Academy’s yearbook. I found Timberg’s photograph, a handsome man with a strong jaw and intense eyes. We met the next day at an Annapolis restaurant, a few hundred yards from the academy’s gates. The man in the photograph wasn’t there. A Viet Cong grenade blew that midshipman’s visage away when he was 26, 13 days before he was due home. His future was bright, as Timberg said later, until it wasn’t. He endured dozens of surgeries including one without anesthesia that was so traumatic that he swears the doctor aged before his eyes during the operation.

What were left almost a half-century later were layers of scar tissue, but he still had the fierce green eyes of his youth. Timberg didn’t really know my father—Bob was set for the Marines; my dad wanted to be a pilot—but he had set aside a day to show me around the academy. I was in the middle of doing some heartbreaking research on my father, who was killed in an EA-6B crash off the USS Kitty Hawk when I was 13, hoping I could make sense out of it all in a book.

Timberg had the easy-to-confide-in manner that all good reporters possess, and we were soon trading stories about our lives. He returned stateside after many surgeries and set upon finding something that mattered to him as much as being a Marine. His first wife told him he wrote beautiful letters from Vietnam, and on that flimsy detail he became a journalist. Through a quirk of the job market he found himself in the shadow of the academy at the Annapolis Capital and then working in the Washington bureau of the Baltimore Sun. Timberg often told himself that he didn’t want his life defined by his Vietnam year or his disfigurement, but it was there every day. When kids would gawk and shriek at his face, he’d yell and scold their parents. He tried to put Vietnam away, but after he wrote a piece for Esquire about an academy boxing match between Oliver North and James Webb, he turned to The Nightingale’s Song, an account of the academy’s five most famous, or notorious, 1960s graduates—John McCain, North, Webb, Bud McFarlane, and John Poindexter—following their lives from Annapolis to Vietnam and then onto Washington. Two of them became senators and the other three were indicted, but all five had something in common with Timberg: They all engaged in clumsy, sometimes heroic, sometimes criminal attempts to rewrite American life after the fall of Saigon.

Timberg spent more than a decade working on The Nightingale’s Song, begging his bosses at the Sun for multiple extensions as he essentially wrote five book-quality profiles of his chosen men. He had ambivalent feelings about the actual mission in Vietnam but not about the dedication of the Nightingale Five. He attended journalism school at Stanford and his problem with the liberal students wasn’t their opposition to the war, but their refusal to put anything on the line. He had more respect for the conscientious objectors than for those lounging on endless student deferments. He was fascinated by the quintet, disillusioned and scarred from Vietnam, who returned to service after hearing the “nightingale song” of Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America.” If the book has a fault, it’s Timberg going light on the excesses of Poindexter, McFarlane, and North, whom he didn’t think was all that bright. But these were Timberg’s brothers, in a sense; complete objectivity would have been impossible.

[I]n those early days of Iran-Contra, I picked up a familiar and troubling aroma. Others saw greed, naked ambition, abuse of authority, a breathtaking disdain for Congress and the federal bureaucracy. I saw those things, too, but what I smelled was cordite, burning shitters, the disinfectant odor of hospitals. And somehow, it seemed, the Academy was mixed up in this, too. … As the bizarre tale unfolded, blossoming into the gravest constitutional crisis in a decade, I kept picking up echoes of Vietnam and an ever more insistent refrain—Ollie, Bud, and John. I remember thinking that perhaps Iran-Contra was at least in part the bill for Vietnam finally coming due.

The book helped me understand my father’s time at the academy and it was a privilege to get a tour of Bancroft Hall, the academy’s massive residential hall, by a man who’d paid the penultimate price. But there was one thing missing in The Nightingale’s Song that I didn’t quite understand. Timberg wrote in the preface that he was an Annapolis grad but never described the horrors that he personally survived. There is very little in The Nightingale’s Song about Timberg’s personal struggle or his ideological view on the quagmire.

At lunch, I mentioned to him that my mother had not gone through my father’s cruise box since the accident. I told him that I couldn’t understand why she wouldn’t want to look in there again. Timberg put his fork down and sighed.

“I’ve got a box of my own from my Vietnam tour. It’s filled with pictures and letters. I’ve never looked in there. I’m not sure I could handle knowing what I was like before that.”

I think I understood what he meant. Late in life, Timberg found himself staring at his face in the mirror and saying, as he told NPR’s Fresh Air: “OK, enough already. The joke’s over. Let’s go back to where we were.”

Late in life, he finally opened the trunk and started digging. His last book, Blue-Eyed Boy: A Memoir, found Timberg, at 70, facing his past, and it is so tragic and horrific—words he’d hate to hear used to describe him—that I now understood why he spent a lifetime avoiding it. He found medical documents where his appearance was depicted as “highly repugnant.” He remembered a nurse referring to him simply as “The Burn.” He took the title of his book from one of his favorite E.E. Cummings poems that includes the stanza:

Jesus

he was a handsome man

and what i want to know is

how do you like your blue-eyed boy

Mister Death

Timberg could project the vibe of the gruff Marine he once was, but he had a softer side that he seldom let people outside of his family see. On the first weekend his children visited him at his apartment in Annapolis after he and his wife had separated, Timberg had his kids decorate two pieces of poster board on which he’d written two poems— one was “the blue-eyed” boy and the other was the poem F. Scott Fitzgerald used at the beginning of The Great Gatsby. He then took his four kids to a record store to buy a copy of Sgt. Pepper’s, which he used to audio-christen his new place. The record came out the year he was wounded. While many saw the ex-Marine hard-ass he once was, Timberg introduced his children to The Band, Dylan, and Coltrane. He wrote about Camus and morality while at the academy. Politically, he was more liberal than many of the figures he wrote about, but he worked scrupulously to be fair to people even if he disagreed with them. (When we met, he laughed about how that school of thinking had fallen out of favor.)

I don’t think he ever solved the tragic riddle that was Vietnam. But he did still believe in the honor he learned there and at the academy. While fact-checking my book, I received an initially angry call from Timberg. He enjoyed the book, but he thought I’d made him appear too heroic in a brief passage.

“I want you to make it clear that I was wounded while delivering paychecks, not leading troops into battle,” Timberg told me. He had a hatred for phoniness that he applied most rigorously to himself and in his final months left him shaking his head at the concept of Donald Trump.

The night after our visit, I was exhausted following a dinner with one of my dad’s flying buddies, an egomaniacal technocrat whom Timberg would have hated. As I piled into my car for the long drive back to New York, my phone rang. It was Bob.

“I can’t believe I didn’t offer you a place to stay tonight. Do you need a place? There’s a spare room. It’s yours.”

I told him I couldn’t; there was a flight to catch the next day. But I clicked off the phone and wept at his simple offer of kindness.

Later in life, Timberg had a different response to the kids who screamed at his appearance: He smiled back at them and waved. After I heard about his death, I watched some old clips of Timberg from a C-SPAN interview he gave decades ago. He looked different, then. I realized something. As he aged, he somehow, imperceptibly, grew into the face that was shaped out of spare skin and bone grafts.

Robert Timberg was a good man dealt a bad hand who still built a wonderful life. And I will miss him.