On Aug. 9, one year ago, Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown after a brief scuffle in the middle of a small street in Ferguson, Missouri. There wasn’t any video of the encounter, but many bystanders and local residents saw the aftermath. For four hours, Brown’s body sat in the summer sun, slumped and face down, blood pooling in the street where he was killed. Neighbors, shocked at the violence and the police’s disrespect for Brown’s corpse, took photos and shared video. “They killed him for no reason … they just killed this n—er for no reason,” said one man in a video recorded just after shooting. “Do you see a knife? Do you see anything that would have caused a threat to these motherf—kin’ police? They shot that boy because they wanted to shoot that boy in the middle of the motherf—kin’ day in the middle of the motherf—kin’ street.”

But Brown wasn’t the first unarmed black person killed by police officers in 2014, although he was the first to inspire mass demonstrations, riots, and an unprecedented, draconian police response of armored vehicles, automatic weapons, and tear gas. He wasn’t even the first unarmed black person killed that summer. That was Eric Garner, a Staten Island man who was killed a month earlier. In the video of his arrest and death, he’s surrounded by police, arguing. “I didn’t do nothing,” he tells an officer. “Every time you see me, you want to harass me, you want to stop me.” An officer puts him in a chokehold, while others hold him face down on the sidewalk. He pleads, “I can’t breathe,” but police continue the arrest. They turn over his unconscious body. An hour later, he’s pronounced dead.

Garner’s death sparked outrage. It even produced protests and demonstrations. But it didn’t cause anything like the events in Ferguson. What was different about the death of Michael Brown?

Part of it was the place where Brown died. St. Louis County, shaped by decades of redlining and white flight, was segregated and thick with racial tension. Worse, in small towns like Ferguson, municipal governments were openly predatory, extracting heavy fees from black residents through overpolicing and an opaque system of municipal courts.

Yes, Brown’s confrontation with Wilson was fraught and complicated. Just minutes before, Brown and a friend had stolen a pack of flavored cigars from a nearby convenience store, and forensic evidence showed a clear struggle between Brown and Wilson. Insofar as there’s an accurate picture, it’s of a police stop that escalates into a fight and then a shooting, with bad judgment on both sides. As the Department of Justice concluded in its investigation, “There is no credible evidence that Wilson willfully shot Brown as he was attempting to surrender or was otherwise not posing a threat.”

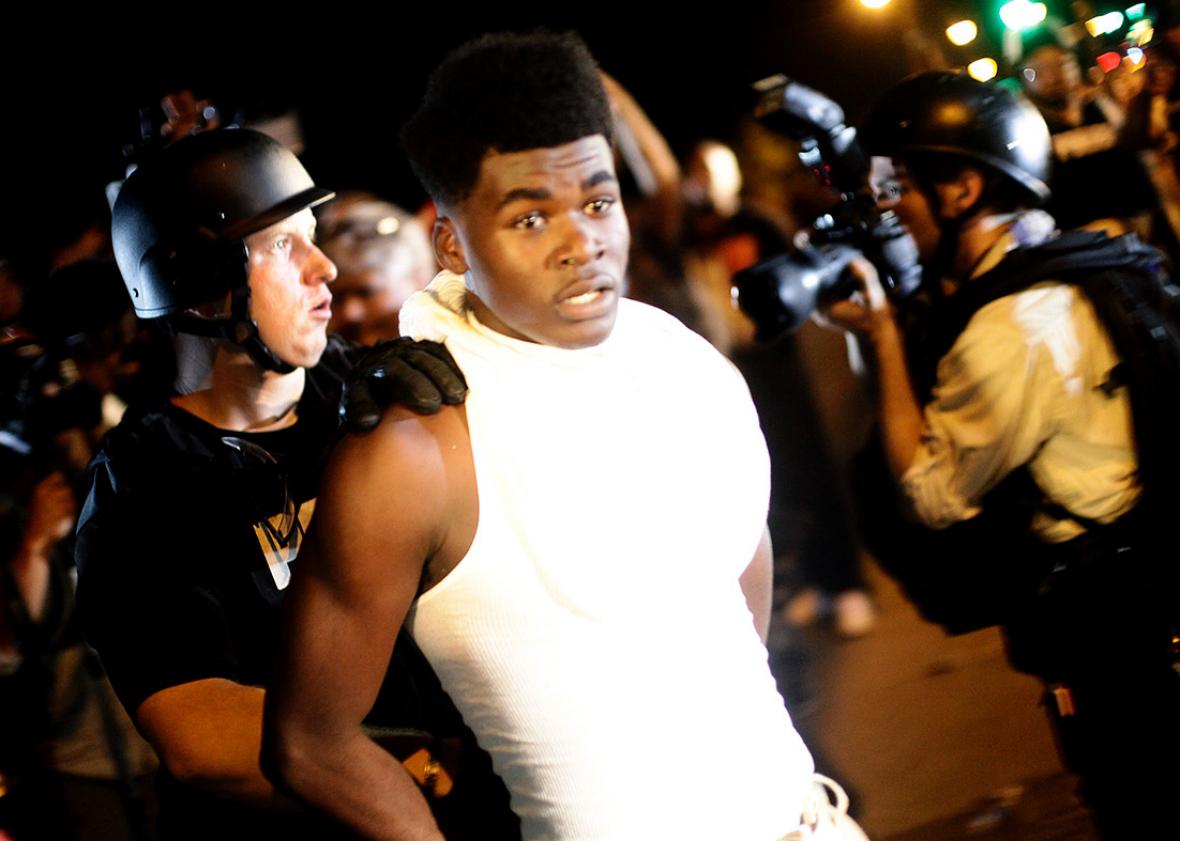

But no one knew that on Aug. 9, 2014. On that Saturday, the only thing anyone knew was what they saw and heard: An unarmed teenager was dead in the streets, with little word from the police. And in that moment, the powder keg of Ferguson and St. Louis County erupted. People wanted answers. Why did police leave Brown’s body in the street? Why, later, did they bring guns and dogs to confront protesters and concerned citizens?

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

Frustration boiled over into anger, and anger boiled into protests and disorder, which were met with heavily armed, militarized police. Across the country, on cable networks and through social media, Americans watched armored vehicles move down small-town streets as military-clad police officers shot tear gas into crowds of peaceful demonstrators.

There was more to Ferguson than violence, however. There was activism. Two now-prominent activists, Deray Mckesson and Johnetta Elzie met in Ferguson, where—writes Jay Caspian Kang for the New York Times Magazine, they were “radicalized,” and where they honed a new kind of advocacy centered on social media. “Their innovation has been to marry the strengths of social media — the swift, morally blunt consensus that can be created by hashtags; the personal connection that a charismatic online persona can make with followers; the broad networks that allow for the easy distribution of documentary photos and videos,” writes Kang, “with an effort to quickly mobilize protests in each new city where a police shooting occurs.”

Thanks in part to Elzie, Mckesson, and activists like Alicia Garza, the events provoked by the death of Michael Brown would coalesce into the “Black Lives Matter” movement, which—a year later—is one of the most vibrant protest movements in recent memory.

But this just takes us back to our first question: What was different about Michael Brown? Why was he the catalyst for protest and conversation, as millions of Americans began talking about race, racism, and policing in ways we haven’t seen since Rodney King was beaten by Los Angeles police officers in 1991?

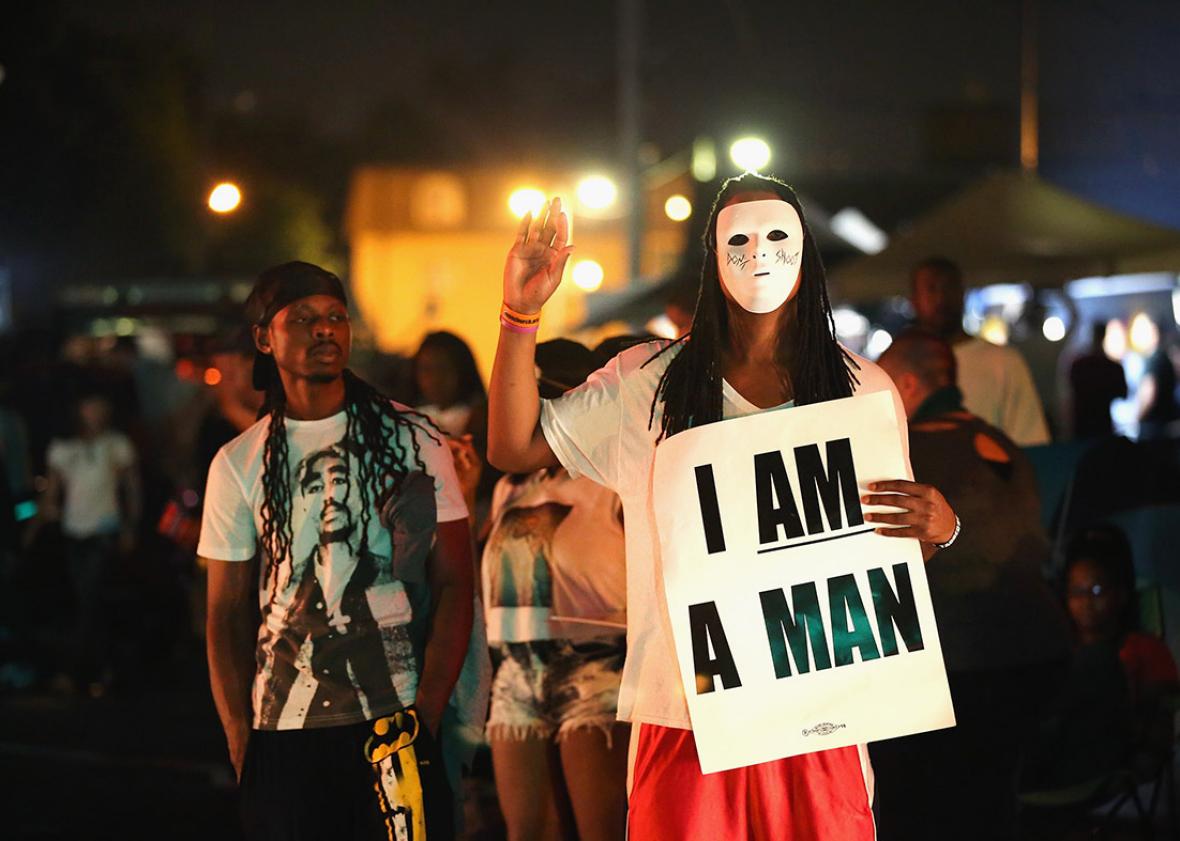

Photo by Joshua Lott/Reuters

It’s anti-climatic, but the answer has a lot to do with timing. With two police shootings in the weeks before, the world was watching—and thinking—when Brown was gunned down. Just two weeks after Garner died in a police chokehold, there was John Crawford, 22, who was killed while carrying a pellet gun in an Ohio Wal-Mart. A customer called 911, telling dispatchers that Crawford was pointing the gun at customers. (He later recanted.) Police arrived on the scene, and fatally shot Crawford while he was on his cellphone talking to the mother of his two children. And each incident compounded the other. Conversations about police violence after Crawford’s death built on ones around Garner’s death, and the entire discussion of Michael Brown was informed by those previous cases, and soon, subsequent ones. For example, two weeks after Brown died, Kajieme Powell, 23, was shot and killed in St. Louis after stealing snacks from a convenience store. Cops claimed he attacked them with a knife, which forced their hand.

Americans didn’t just hear about these incidents. They saw them as raw video, collected by cellphones and surveillance cameras, and broadcast by social media. And in almost every case, what they saw ran counter to what the police claimed: Crawford wasn’t threatening anyone; Powell, in reality, wasn’t even near the police when they killed him. For the first time, at least since Rodney King, Americans who distrusted the police had clear evidence for their beliefs, and Americans who typically placed their faith in law enforcement were newly challenged in their trust.

With that as the backdrop, it’s no wonder that Ferguson—already troubled with inequality, segregation, and unfair policing—was the town that eventually burned. Brown’s death was the final spark in a summer of violence against black Americans, exacerbated by police misconduct and the attacks on Brown’s character, meant to minimize or even excuse his death. And in turn, this explosion inaugurated a new, more urgent phase in the national argument over racism.

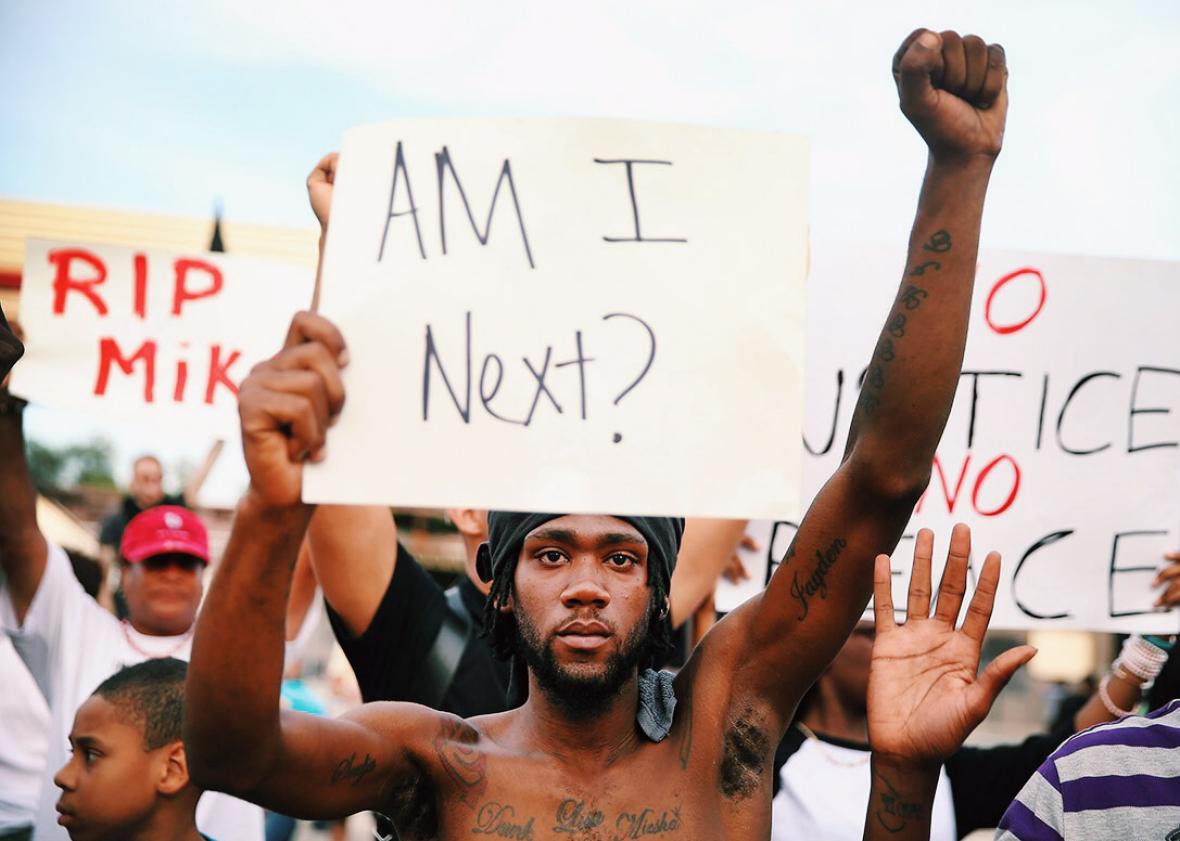

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

You could see this in the White House’s response. At various points in his presidency, Barack Obama had been forced to address race: When Henry Louis Gates was arrested at his home in Cambridge; when Trayvon Martin was shot on a quiet Florida street, and when George Zimmerman was acquitted in the killing; and when Jordan Davis was shot dead in a parking lot for listening to loud music.

But for as much as Martin and Davis’ deaths were traumatic, they were also in a different category than Garner or Brown. Gates was arrested, yes, but he wasn’t harmed. And neither Martin nor Davis were killed by police officers—they were killed by private citizens. And while that provoked a conversation about black lives and bias, it was distinct from the policy questions evoked by police shootings.

With Ferguson, President Obama was more reticent to broaden the conversation from policy to racism and bias. But his administration took action in a way that wasn’t true in the previous cases. Then–Attorney General Eric Holder visited the town, while the Department of Justice launched an investigation of police practices in Ferguson and other municipalities. Wide coverage from major media outlets put the events on the national radar beyond social media. And unlike past incidents, that attention wouldn’t break. We had entered a new reality.

Here, the brutal beating of Rodney King 24 years earlier is a useful contrast. When he was beaten, raw video was unusual. It, plus cable news, is why Americans were jolted into national debates over police violence. Put differently, King wasn’t the first person assaulted by the Los Angeles Police Department. But he was the first one whom millions of Americans had ever seen. For the victims of police brutality, and blacks in particular, it was vindication of pervasive mistreatment at the hands of law enforcement. And for white Americans who were skeptical—or more likely, indifferent—it was a shock to the conscience.

Now, of course, that kind of video is ubiquitous, so much so that we aren’t even interested in who took the footage. (By contrast, we know who took the Rodney King video: George Holliday.) And in the months after Ferguson, Americans viewed a steady stream of images from police stops gone wrong. The victims were almost always black, the offenses were almost always minor, the outcomes were often death, and—most importantly—police accounts never quite matched the footage.

That September, Americans watched video from the dashboard camera of South Carolina State Trooper Sean Groubert, who shot a black motorist, Levar Jones, after he tried to comply with the trooper’s request. As Jones reached down to grab his wallet and driver’s license, Groubert, who is white, shot him. “I just got my license! You said get my license!,” yelled Jones, who was shot several times but remarkably survived. Groubert was fired and charged with felony assault and battery.

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

That November—several weeks after a St. Louis grand jury declined to indict Officer Wilson in the death of Brown, sparking riots and protests in Ferguson and surrounding areas—Cleveland police officers Frank Garmback and Tim Loehmann killed Tamir Rice, 12, while he stood in an empty park, holding a lifelike toy gun. In their account, Officers Garmback and Loehmann say they approached in their car, shouted for Rice to drop his weapon, and fired when he reached for his waistband. Surveillance footage, on the other hand, showed a different story. Rice was standing in the park, bored and aimless. Without warning, a police cruiser barreled onto the scene. Officer Loehmann leapt out of the car, and started shooting. Seconds later, Rice was on the ground, dying. “Shots fired, male down,” said one of the officers to dispatch. “Black male, maybe 20, black revolver, black handgun by him. Send E.M.S. this way, and a roadblock.” Neither officer gave first aid.

Rice’s death was followed, this past April, with the killing of Walter Scott in North Charleston, South Carolina. According to the official report, Officer Michael Slager stopped Scott for a broken taillight, and Scott resisted arrest, taking control of Slager’s Taser. Fearing for his life, Slager used his weapon, killing Scott. But there was a bystander, and in his recording, Scott wasn’t a threat. Yes, he struggled with Officer Slager, but then he ran away. Slager didn’t pursue him. Instead, he stopped, raised his gun, and fired eight times. He then cuffed the bullet-ridden Scott and placed the Taser near his body. The city took action and fired Slager, while Scott joined the growing roster of black Americans killed by police, with deaths broadcast to the world writ large.

One week later, in Baltimore, police arrested 25-year-old Freddie Gray. In the video, cops are dragging an incapacitated Gray to the police van. There—according to an official autopsy—he was hogtied and banged against the walls, as officers drove back to the station. The “rough ride” severed his spine, and he was taken to a hospital, where he died. As with Brown and Ferguson, Gray’s death sparked violent unrest from a city that, like St. Louis, is defined by segregation and deep inequality.

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

After Baltimore, there was McKinney, Texas, where police arrested a 14-year-old girl for allegedly trespassing at a pool party. In a bystander’s video, she’s held to the ground. When two other teenagers, both black, come to assist her, the officer—who is white—points a gun at them. After McKinney, there was Prairie View, Texas, where a state trooper stopped Sandra Bland, 28, for a minor traffic violation. When she refused to put out a cigarette, the officer escalated the situation, threatening her with a stun gun and detaining her for “resisting arrest.” She was arrested and sent to jail, where—three days later—officials found her dead in her cell, of an apparent suicide.

The June massacre in Charleston, South Carolina—where a young racist gunman killed nine worshippers at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, including the pastor, State Sen. Clementa Pinckney—isn’t related to police violence, but it resonated nonetheless. In the same way that Ferguson and Baltimore are tied to long legacies of segregation and discrimination, Charleston was irrevocably tied to our history of racism and its presence in modern America. The attack was on a historic black church, and the alleged killer, Dylann Roof, saw his act as a blow for white supremacy. The unavoidable role of racism in inspiring the Charleston killings forced conversations that we often avoid, from the rapid and successful push to remove the Confederate flag from public buildings to President Obama’s remarkable eulogy for Rev. Pinckney, in which he addressed American racism head-on. “None of us can or should expect a transformation in race relations overnight. Every time something like this happens, somebody says we have to have a conversation about race. We talk a lot about race. There’s no shortcut. And we don’t need more talk.”

Each incident generated new coverage, new protests, new stories, and new activism. Put another way, in 1992, Americans eventually stopped talking about Rodney King. But because of the steady drip of incidents and evidence, we have never stopped talking about Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Tamir Rice, and we won’t stop talking about Freddie Gray, Clementa Pinckney, Sandra Bland, and all of the others. Their lives are part of a new, wrenching, and unprecedented argument about race and racism in today’s America.

Photo by Adrees Latif/Reuters

Often—maybe most of the time—it’s hard to step back and place proceedings in their proper context. Fights that feel major often look minor in the eyes of history, while small events can have lasting significance. In the 12 months since Ferguson, there’s no question: It’s just as important as it seems. We’ve had a national reckoning with race and racism that surpasses the debates over Rodney King and the Los Angeles riots, or the controversies around Hurricane Katrina and the botched evacuation of New Orleans. More Americans are skeptical of police claims than they were before Ferguson; more Americans think racism is a pressing issue for the country than they did before Brown’s death; mainstream institutions like Starbucks (which tried to begin conversations about race) and MTV (which has commissioned research and aired a documentary on white American identity) are confronting questions of racial privilege; and more politicians are wading into issues of racial justice, pushed by belief, circumstance, and the vocal demands of the public and activists alike.

A year ago, “Black Lives Matter” was a hashtag. Now, it’s an important part of the fight for the Democratic presidential nomination. Leading leftist candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders harmed himself when he couldn’t answer activist concerns about ending police violence against black Americans. Now he’s embraced their rhetoric at campaign events across the country. Likewise, Hillary Clinton—the likely Democratic nominee—has stepped forward with speeches on racism and several proposals for police and criminal justice reform. The candidate who once shied away from race and gender in her 2008 presidential run has, early in the Democratic primary, openly criticized racism and bias among whites. “Our problem is not all kooks and Klansmen. It’s also the cruel joke that goes unchallenged. It’s the offhand comment about not wanting those people in the neighborhood,” she said in a speech after the Charleston shooting. “Let’s be honest, for a lot of well meaning, open-minded white people, the sight of a young black man in a hoodie still evokes a twinge of fear.”

Photo by Jim Young/Reuters

And President Obama has become increasingly forthright on bias and racism. “[T]he legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, discrimination in almost every institution of our lives: That casts a long shadow,” he said in an interview with comedian Marc Maron. “And that’s still part of our DNA. That’s passed on. We’re not cured of it—racism. We’re not cured of it. And it’s not just a matter of it not being polite to say nigger in public.”

In terms of policy or politics, it’s hard to say what will follow, although “Black Lives Matter” and other activists have added urgency to the drive for criminal justice reform. But what we can say, with near certainty, is that this conversation will continue, driven by more footage of more black people killed or injured in confrontations with police. Last week it was the release of a body-camera video of Samuel Dubose, a 43-year-old unarmed black man who was shot in the head by a University of Cincinnati police officer during a routine traffic stop. The officer claimed he shot in self-defense, that he “almost was run over by the driver of the Honda Accord.” The footage revealed another unprovoked death.

If Ferguson was an earthquake—a tectonic shift in our arguments over race and racism—then a year later, we’re not just feeling the aftershocks. We’re preparing for the next blow.