Most of the time, when we talk about immigration, we’re talking about Latin America. Donald Trump isn’t threatening to round up Irish immigrants in Boston who entered the country illegally or to build a wall between us and Canada; he’s threatening Latinos and tapping into an ugly strain of racist nativism. It’s why “anchor baby”—slang for the American-born children of unauthorized immigrants—is such a charged term. To many, it’s racial code for often brown-skinned, Spanish-speaking children.

Of course, rhetoric aside, America’s immigrant community goes beyond Latino and Hispanic Americans. It includes Africans, Europeans, and Asians, one of the fastest growing groups in the country. Not all Asians are tied to the immigrant experience—more than a quarter are native-born, with long and durable ties to the United States. But the large majority are foreign-born, with roots in a variety of different countries, from China and Japan to Korea, Vietnam, India, and Bangladesh. Moreover, they’re a rising share of the electorate—in 1996, just 1.6 percent of voters were Asian. In 2012, it was 3.4 percent. As second- and third-generation Asian Americans take the stage in national life, that voting block will increase.

When Republicans attack immigration—and increasingly, immigrants—we know it alienates Hispanic and Latino voters. Indeed, between Trump and his chorus of imitators, the party has all but abandoned its outreach to that community. But in this analysis, we shouldn’t ignore Asian Americans. This rhetoric matters to them too, and if Republicans aren’t careful, they’re set to lose two groups and likely seal their fate for next November.

How do we know that Asian voters care about immigration? Let’s look back to the previous presidential election. So little of how Barack Obama won in 2012 was a surprise. He captured young voters and cleaned up with single women; he struck gold with Latinos and won the entire black vote, again; and he was weak, as expected, with most white Americans. However, there was one shock: Obama scored an enormous win among Asians. His 73 percent share of the Asian vote was a significant increase from the previous election and a bright spot in his overall performance.

It would have been one thing if, like blacks, Asians were Democratic stalwarts. But they weren’t. A solid 44 percent supported George W. Bush in the 2004 presidential election, and a sizable minority—35 percent—voted for John McCain in the 2008 election. The reason is straightforward: As a whole, Asians are closer to the social and economic mainstream than other minority groups. They are the “highest-income, best-educated and fastest-growing racial group in the United States,” notes the Pew Research Center. “They are more satisfied than the general public with their lives, finances and the direction of the country, and they place more value than other Americans do on marriage, parenthood, hard work and career success.”

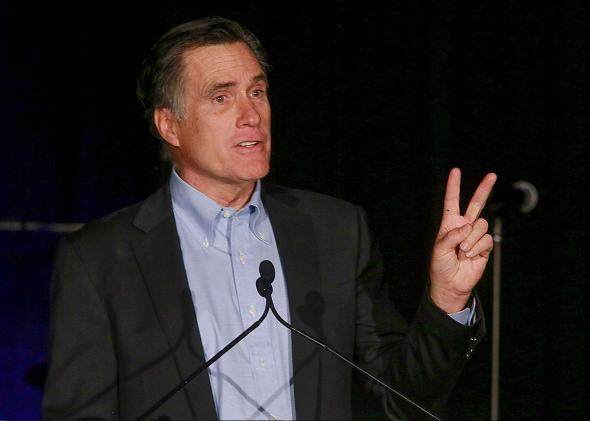

In 2012, Asians were primed to follow the national trend and vote a little more Republican. But they didn’t. Just 26 percent voted for Mitt Romney, the lowest GOP total in 20 years. What happened? What turned a small Democratic edge into an outright advantage?

Again, the answer is immigration, and specifically, the sense of exclusion that came from the GOP. In the 2012 primary, like this one, Republicans were torn over immigration policy, with candidates having a strong incentive to oppose comprehensive reform. Throughout the primary process, candidates fought to surpass one another with draconian solutions for dealing with unauthorized immigrants, with Romney touting “self-deportation” in his pitch to Republican voters. He won the nomination, but the phrase was an albatross on his general election campaign. In a 2014 study, researchers at Vanderbilt University measured the impact of that rhetoric on Asian voters. How would they react to feeling excluded or questioned on their citizenship? “The simple intervention of making an Asian subject feel excluded with respect to ‘Americanness’ and being suspected of not being a U.S. citizen increased negative dispositions towards the Republican Party and increased positive views of the Democratic Party,” write the authors. Put simply, when confronted with exclusionary rhetoric, Asian voters tied the Republican Party to racial discrimination.

Last year, in the midterm elections, it looked like Republicans recovered from their 2012 rout with Asians. In exit polls, 50 percent voted for Democrats, versus 49 percent for Republicans. If that’s accurate, then the picture isn’t as bad as it seems. But there’s always been a midterm swing toward Republicans, and several polls—including in-language surveys from polling firm Asian American Decisions—show a larger Democratic advantage than appears in that exit poll. Indeed, in its recent probe of party affiliation, Pew found an almost 3-to-1 divide among Asians: 65 percent identified with the Democratic Party, 23 percent with the GOP.

Still, outreach isn’t hopeless, especially in an open election year without an incumbent on the ballot. But that assumes that Republicans can get their base under control, or at least behind rhetoric that doesn’t antagonize immigrant groups and those with ties to immigrant communities. This could happen, but because of Trump, it looks like a long shot. Trump isn’t just popular; he’s shaping Republican policy, and several candidates have even turned against birthright citizenship—a historic achievement of the once–party of Lincoln.

Maybe this won’t matter for 2016. After all, most Americans aren’t paying attention to the race thus far. But that’s small consolation. Democrats are watching the Republican primary. They are recording and polling and testing. Come next year, they will blanket immigrant communities with the greatest hits of Republican rhetoric, and over the course of the campaign, countless people—teachers, factory workers, small business people, and others—will remember the comments about “illegals” and “anchor babies.” And they’ll act accordingly. In turn, this will leave Republicans in a tight spot. To win without minorities, they’ll have to find and mobilize even more white voters: men and women who aren’t as tied to the political system, people who are angry and disaffected from their leaders. Trump supporters.

On Friday, a writer for the Federalist—a conservative website—asked if the GOP was the “party of freedom” or the “party of white identity.” If the party keeps moving on its present path, there will be no answer but the latter.