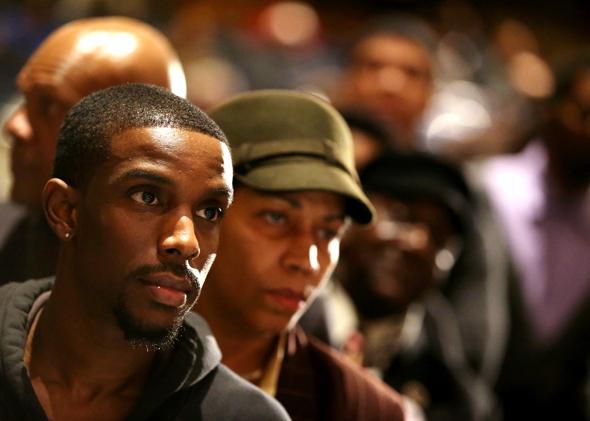

In cities across the country, crowds are protesting police violence against unarmed black men. Demonstrators want justice, not just for Michael Brown, but for Eric Garner, John Crawford, and Tamir Rice, the 12-year-old boy killed by Cleveland police last month. To that end, they’ve stopped parades and blocked highways in an effort to show the value of a black life.

But to some critics, this outrage is misplaced. “Somebody has to tell me, something somebody needs to tell me why Michael Brown has been chosen as the face of black oppression,” said MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough on Monday morning, during his daily show. His co-panelist, Donny Deutsch, agreed. “It’s not a black-white situation. It’s a thug-police officer situation,” he said. “Where are the angry crowds demanding justice for blacks such as these, who were wiped out in St. Louis by other blacks in recent memory?” wonders Deroy Murdock in a column for National Review. “One can hear birds chirp while listening for public outcry over the deaths of black citizens killed by black perpetrators. Somehow, these black lives don’t seem to matter,” writes Murdock, who doesn’t note that—in those cases—perpetrators are usually caught and convicted. And then there’s former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, who—after President Obama spoke on Ferguson—told CNN that “[Obama] also should have spent 15 minutes on training the [black] community to stop killing each other.”

This basic question—“Where is all the outrage over black-on-black crime?”—is raised whenever black Americans protest a police shooting, or any other violence against unarmed black men. “Nationally, nearly half of all murder victims are black,” wrote conservative commentator Juan Williams after Trayvon Martin was killed in 2012, “And the overwhelming majority of those black people are killed by other black people. Where is the march for them?”

There are huge problems with “black-on-black crime” as a construct, mostly dealing with the banality of intra-racial crime, the foolishness of attributing violent criminality to blackness—rather than particular conditions faced by some black people—and the injustice of treating all blacks as criminally suspect because of the actions of a small minority.

Let’s ignore those.

Instead, let’s look directly at the question raised by Murdock, Giuliani, and Williams—“Do black people care about crime in their neighborhoods?” They treat it as a rhetorical concern—a prelude to broad statements about black American concerns. But we should treat it as an empirical question—an issue we can resolve with some time and research.

This isn’t as easy as it sounds. While blacks are more likely to face criminal victimization than other groups, that doesn’t tell us how black Americans feel about crime and where it ranks as a problem for their communities. For that, we have to look to public opinion surveys and other research. And while it’s hard to draw a conclusive answer, all the available evidence points to one answer: Yes, black people are concerned with crime in their neighborhoods.

First, a little context: In the last 20 years, we’ve seen a sharp drop in homicide among blacks, from a victimization rate of 39.4 homicides per 100,000 in 1991 to a rate of roughly 20 homicides per 100,000 in 2008. Likewise, the offending rate for blacks has dropped from 51.1 offenders per 100,000 in 1991 to 24.7 offenders per 100,000 in 2008. This decrease has continued through the 2010s and is part of a larger—and largely unexplained—national drop in crime.

But while black neighborhoods are far less dangerous than they were a generation ago, black people are still concerned with victimization. Take this 2014 report from the Sentencing Project on perceptions of crime and support for punitive policies. Using data from the University of Albany’s Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, the Sentencing Project found that—as a group—racial minorities are more likely than whites to report an “area within a mile of their home where they would be afraid to walk alone at night” (41 percent to 30 percent) and more likely to say there are certain neighborhoods they avoid, which they otherwise might want to go to (54 percent to 46 percent). And among black Americans in particular—circa 2003—“43 percent said they were ‘very satisfied’ about their physical safety in contrast to 59 percent of Hispanics, and 63 percent of whites.”

More recent data shows a similar picture. In 2012, Gallup found that, compared to the general public, blacks were more worried about “being attacked” while driving their car, more worried about being the victim of a hate crime, and—most salient for our discussion—more worried about “being murdered.” Likewise, according to a 2013 survey for NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard School of Public Health, 26 percent of black Americans rank crime as the most important issue facing the area they live. That’s higher than the ranking for the economy (16 percent), housing (4 percent), the environment (7 percent), social issues (4 percent), and infrastructure (7 percent). And in a recently published survey for Ebony magazine and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, 13 percent rank violent crime as a top issue—which sits in the middle of the rankings—and 48 percent say that the black community is losing ground on the issue.

Finally, Atlantic Media’s “State of the City” poll—published this past summer—shows an “urban minority” class that’s worried about crime, and skeptical toward law enforcement, but eager for a greater police presence if it means less crime. Just 22 percent of respondents say they feel “very safe” walking in their neighborhoods after dark, and only 35 percent say they have “a lot” of confidence in their local police. That said, 60 percent say hiring more police would have a “major impact” on improving safety in their neighborhoods. And while “urban minority” includes a range of different groups, there’s a good chance this is representative of black opinion in some areas of high crime and victimization, given the large black presence in many American cities.

It’s important to note that this concern with crime doesn’t translate to support for punitive policies. Despite high victimization rates, black Americans are consistently opposed to harsh punishments and greater incarceration. Instead, they support more education and job training.

Beyond the data, there’s the anecdotal evidence. And in short, it’s easy to find examples of marches and demonstrations against crime. In the last four years, blacks have held community protests against violence in Chicago; New York; Newark, New Jersey; Pittsburgh; Saginaw, Michigan; and Gary, Indiana. Indeed, there’s a whole catalog of movies, albums, and sermons from a generation of directors, musicians, and religious leaders, each urging peace and order. You may not have noticed black protests against crime and violence, but that doesn’t mean they haven’t happened. Black Americans—like everyone else—are concerned with what happens in their communities, and at a certain point, pundits who insist otherwise are either lying or willfully ignorant.

To that point, it’s worth noting the extent to which “what about black-on-black crime” is an evasion, an attempt to avoid the fundamental difference between being killed by a citizen and being killed by an agent of law. And it’s not new. “When Ida B. Wells … tried to explain to a wealthy suffragist in Chicago that anti-black violence in the nation must end,” writes historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad for The Nation, “Mary Plummer replied: Blacks need to “drive the criminals out” of the community. ‘Have you forgotten that 10 percent of all the crimes that were committed in Chicago last year were by colored men [less than 3 percent of the population]?’ ”

Regardless of cause or concern, a community doesn’t forfeit fair treatment because it has crime. That was true then when the scourge was lynching, and it’s true now that the scourge is unjust police violence. Say what you will about “black-on-black crime,” just don’t pretend it has anything to do with unfair killings at the hands of the state.