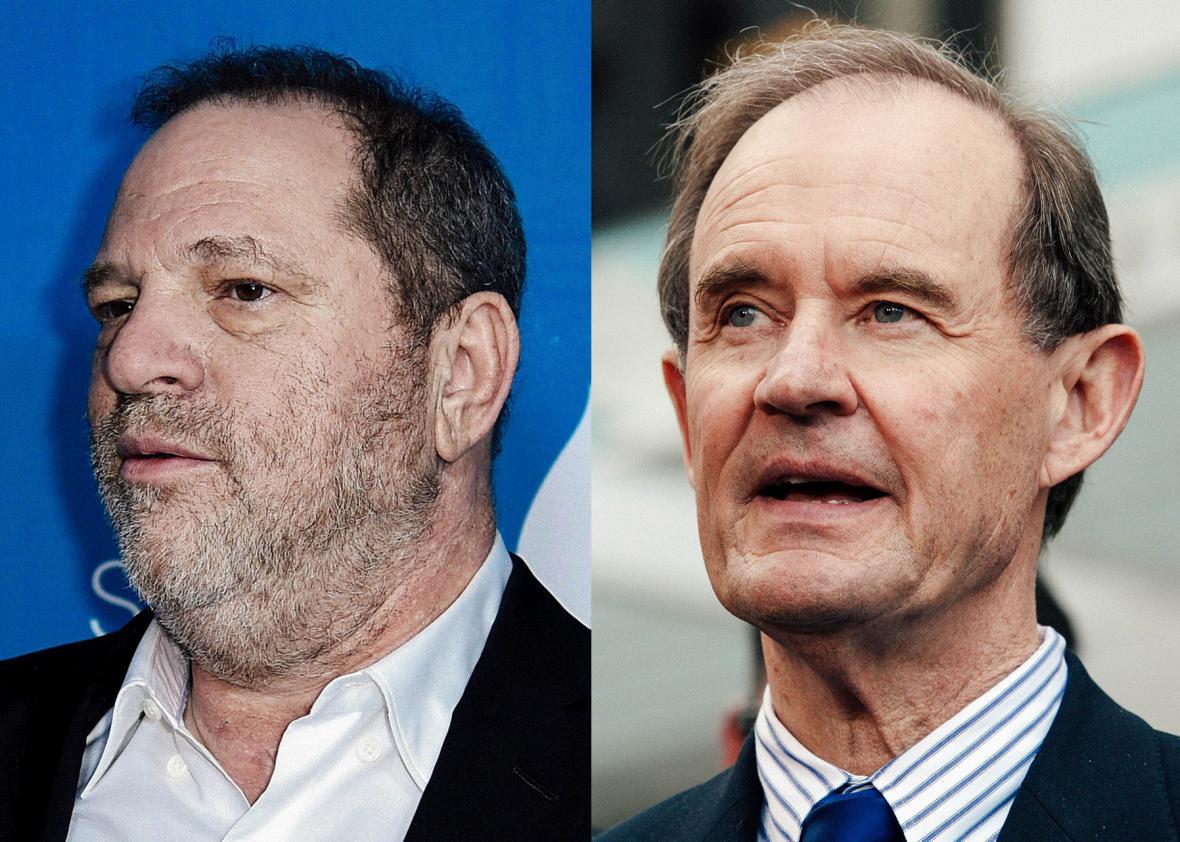

Renowned liberal attorney David Boies represented Al Gore during the contested aftermath of the 2000 election and argued for marriage equality before the Supreme Court. Boies’ progressive legacy, though, is now in question in the wake of revelations about his involvement in the Harvey Weinstein scandal. In October, the New York Times reported that Boies, who represented Weinstein starting in 2015, was aware that the Hollywood mogul had settled with several women who’d accused him of sexual misconduct. Now, Ronan Farrow’s latest blockbuster in the New Yorker has raised the possibility that Boies helped abet a sprawling and costly conspiracy to cover up Weinstein’s misdeeds.

Farrow reports that in 2016, Weinstein enlisted Kroll, a corporate investigation firm, and Black Cube, a private intelligence agency, to try to stop outlets from publishing allegations of his sexual abuse. Kroll and Black Cube agents reportedly met with journalists and victims to obtain information and attempt to quash stories. Boies’ elite firm, which represented Weinstein, contracted with these companies, potentially adding a layer of attorney-client privilege to insulate Weinstein from the intelligence work he commissioned. Boies didn’t hand off all this work to associates. Farrow reports that the lawyer personally signed a contract “directing Black Cube to attempt to uncover information that would stop the publication of a [New York] Times story about Weinstein’s abuses.” Further complicating matters, he did so while his firm was representing the Times in a libel lawsuit.

Boies told Farrow that he didn’t think this was a conflict, explaining that he was doing the Times a favor by pushing the newspaper to vet its Weinstein coverage carefully. “If evidence could be uncovered to convince the Times the charges should not be published, I did not believe, and do not believe, that that would be averse to the Times’ interest,” he told the New Yorker.

This is pretty clearly nonsense. Legal ethics expert and Georgetown Law professor David Luban told us in an email that, at minimum, Boies could have run afoul of Rule 1.7 of New York’s rules of professional conduct, which bars lawyers from representing a client “if a reasonable lawyer would conclude that … the representation will involve the lawyer in representing different interests.” There are exceptions, but they require informed consent from both clients, which Boies did not provide to the Times. “We learned today that the law firm of Boies Schiller and Flexner secretly worked to stop our reporting on Harvey Weinstein at the same time as the firm’s lawyers were representing us in other matters,” the newspaper said in a statement. “We consider this intolerable conduct, a grave betrayal of trust, and a breach of the basic professional standards that all lawyers are required to observe. It is inexcusable and we will be pursuing appropriate remedies.”

Luban also noted that Boies’ sanctioning of intelligence work on behalf of Weinstein could be ethically questionable under Rule 5.3, which prohibits lawyers from directing or approving a nonlawyer’s “specific conduct” that they themselves could not undertake without getting disbarred. Boies’ response to the New Yorker’s revelations suggests he wants to avoid the perception that he violated this particular rule. He told Farrow that his firm “should not have been contracting with and paying investigators that we did not select and direct.” (Emphasis ours.) In Boies’ telling, his firm hired these contractors, who then engaged in legally and ethically dubious conduct—including impersonation and possible fraud—without the firm’s knowledge or supervision.

But even if Boies didn’t direct the behavior of Weinstein’s investigators, he may still have violated state ethics rules. Rule 5.3 also declares that a lawyer is responsible for a nonlawyer’s conduct if he “should have known of the conduct so that reasonable remedial action could have been taken” to mitigate the consequences. Boies arguably should have known that these contractors would use hardball tactics to obtain information. Given that he signed the contract himself, it is reasonable to assume that he knew his actions would lead investigators to engage in sordid, potentially unscrupulous conduct.

In the Trump era, we often measure justice along one simple axis, one that pits the president and his bullying New York attack dogs against legal rules and norms. But there is and has always been a second axis, one populated by respectable, principled attorneys who will work against the rule of law when they are working for the extremely wealthy. Consider Jamie Gorelick, the longtime Democratic activist and deputy attorney general under Bill Clinton, who represented Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump in their business affairs. While Gorelick stepped back in July from handling anything related to Kushner and the Russia probe, her view has always been that everyone deserves quality representation.

It is a long-standing American legal tradition dating back to John Adams that even contemptible people deserve good representation. The problem comes when counsel for the 1 percent finds themselves helping their clients contract out of, or bully their way around, the legal rules imposed upon the rest of us. At that point—and it appears based on Farrow’s reporting that Boies may have crossed that line—it becomes a case of attorneys serving not as zealous counsel but as legal butlers to the too wealthy to fail.

What Boies seems to have done here is the very opposite of fighting for the rule of law. Rather, it looks an awful lot like aiding and abetting a man determined to bypass legal sanctions with money, privilege, and terror. At the very least, he created an attorney-client bubble around grotesque abuse. But Boies also should have known what lawyers and investigators were doing to vulnerable women in the interest of protecting Weinstein. In conceding that he failed to supervise or manage a raft of outside investigators, Boies was also admitting that Weinstein essentially bought his way around his legal relationship with his lawyer, then deployed that same legal relationship for cover.

There are many, many legal stratagems that allow society’s wealthiest to buy their way out of criminal and civil sanctions. In Weinstein’s case, those stratagems have included oppressive nondisclosure agreements and legal threats and attempts to confuse and harass witnesses. Anyone who has watched Donald Trump ooze his way out from under oodles of lawsuits knows that there have always been Platinum Elite workarounds for the rule of law—and lawyers willing to fly you there. This week we learned that Boies may very well be one of them.

Update, 9:00 p.m.: On Tuesday, David Boies sent a statement to all of the employees at his firm Boies Schiller Flexner. In that statement, Boies says he and his firm declined to represent Harvey Weinstein in his efforts to stop the New York Times from publishing a story about his alleged sexual abuse. Nevertheless, Boies states he did execute a contract between Weinstein and a team of private investigators. Weinstein’s “request to contract with investigators seemed at the time, like a reasonable accommodation for a longtime client. I regret having done this,” Boies writes. “It was a mistake to contract with, and pay on behalf of a client, investigators who we did not select and did not control. It was not thought through, and that was my mistake. I take responsibility for that.”

Boies concludes:

Had I known at the time that this contract would have been used for the services that I now understand it was used for, I would never have signed it or been associated in any way with this effort. I have devoted much of my professional career to helping give voice to people who would otherwise not be heard and to protecting the rights of women and others subjection to oppression. I would never knowingly participate in an effort to intimidate or silence women or anyone else, including the conduct described in the New Yorker article. That is not who I am.

You can read Boies’ statement in full here.