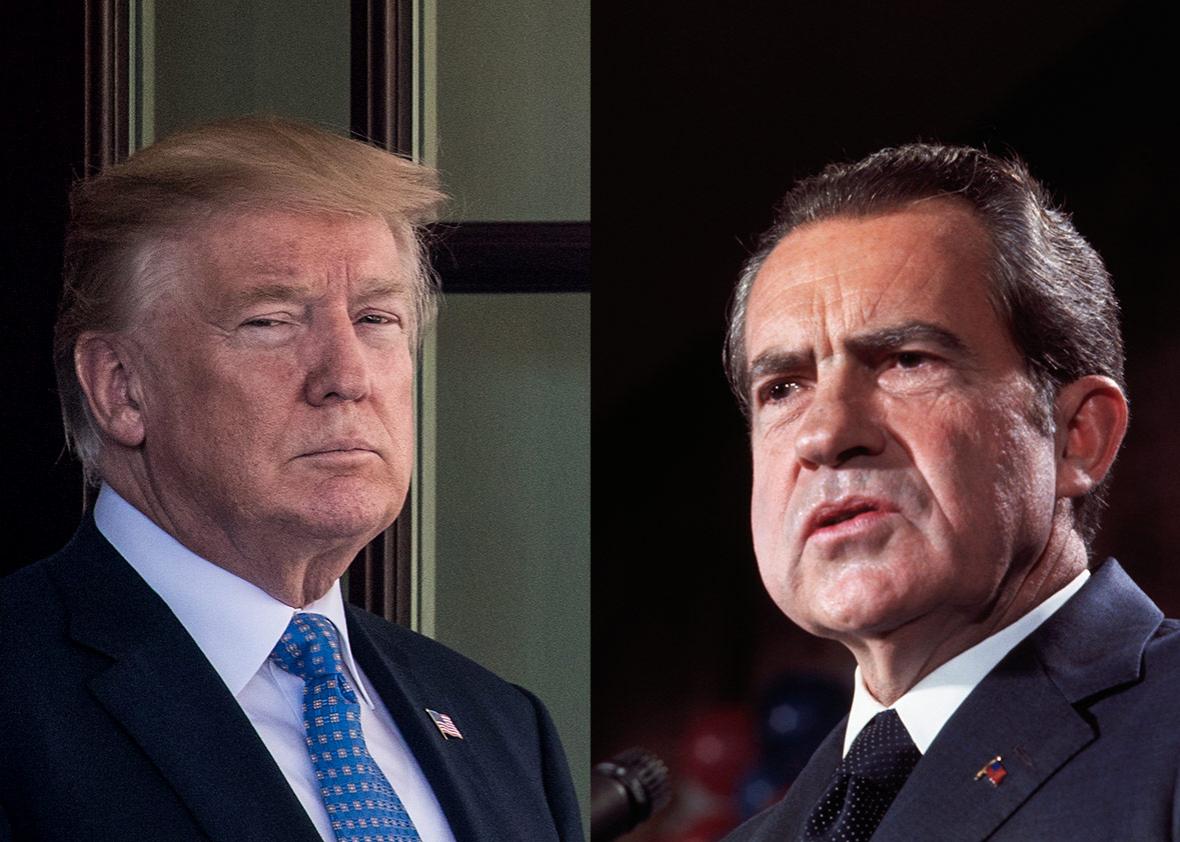

The specter of Watergate haunts the Trump presidency. On a personal level, Donald Trump shares Richard Nixon’s penchant for egregious deceit, petty revenge, and debilitating paranoia. When it comes to governing, he has demonstrated a Nixonian willingness to fire people who refuse to promise him their loyalty. Trump has also taken a page from his predecessor’s playbook in his response to the allegations being made against him. In the same way Nixon and his apologists accused the Democrats of political sabotage and illegal campaign spending after the Watergate break-in, Trump has lately been insisting that Hillary Clinton and the DNC colluded with the Russians.

The charges brought Monday against three Trump associates—including his former campaign manager—marked another stop on the Watergate nostalgia tour: the first indictments.

In the Trump version of this story, Paul Manafort and his deputy Rick Gates got charged with money laundering and tax fraud, and campaign foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos pleaded guilty to making false statements about his contacts with the Russian government. In the Nixon version, the five burglars who’d broken into Democratic National Committee headquarters, got indicted along with the two former White House aides who had organized the break-in, G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt.

The parallels between the two sets of indictments are not straightforward at this point, and it’s not clear how much insight we can glean into our current political moment based on these similarities. The ways in which the indictments differ, however, tell us quite a bit about the situation Trump and his people are in.

At the time of the Watergate break-in, Nixon was running for re-election. When a grand jury handed down a set of indictments on Sept. 15, 1972, that didn’t touch the president or his inner circle, it was cause for celebration in the West Wing. Not only did it mean that the important members of Nixon’s team were safe from prosecution—“We have absolutely no evidence to indicate that any others should be charged,” a Justice Department spokesman had told the press—it also allowed the Nixon administration to blame Watergate on two individuals, Liddy and Hunt, who could be convincingly portrayed as marginal players in Nixon’s operation.

Nixon’s chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, told the president in a meeting on the day of the indictments that having Hunt and Liddy among the individuals indicted “takes the edge off the whitewash.” Haldeman added, “To those in the country, Liddy and Hunt are big men.” Nixon agreed: “Yeah, they’re White House aides.”

John Dean, the White House counsel who helped carry out the Watergate cover-up before turning on Nixon, expressed confidence during that same meeting that “not a thing will come crashing down to our surprise” before the election in November 1972.

Though the total number of people indicted or jailed in connection with Watergate would eventually reach 40, Nixon came away from that meeting in mid-September feeling like everything was under control. “This is war,” he said. “We’re getting a few shots and it’ll be over, and we’ll give them a few shots and it’ll be over.” It wasn’t over.

By contrast, no reasonable person could look at Monday’s news and think Trump is out of the woods now that Manafort, Gates, and Papadopoulos have been hit with charges. On the contrary, the documents released by the Department of Justice suggest special counsel Robert Mueller has only taken his first steps.

In exchange for striking a plea agreement with Papadopoulos, Mueller and his team are presumably getting something quite valuable back in the form of cooperation. (The plea agreement states that after his arrest, Papadopoulos “met with the Government on numerous occasions to provide information and answer questions.”) And in charging Manafort and Gates with a slate of very serious crimes, Mueller’s office is exerting pressure on the two former campaign officials to reveal whatever it is they know about Trump and his closest allies.

By comparison, Nixon officials did not perceive any kind of threat when the “Watergate Seven” were indicted. (The scandal did not fully take off until March 1973, when one of the burglars wrote a letter to the judge in the case informing him that others had been involved in the break-in.) Part of what Nixon had going for him was that, up to that point, the Watergate probe was being handled by people Nixon felt he could trust: The special prosecutor who was eventually appointed to investigate Nixon didn’t enter the picture until May 1973. At the time of the first indictments, Nixon had an attorney general, Richard Kleindienst, who was willing to go on TV and talk about how exhaustive the Watergate investigation had been. He also had a criminal division chief at the Department of Justice, Henry Petersen, who had assured the White House that federal prosecutors would interpret their brief narrowly and would not go on a “fishing expedition as far as White House activities are concerned.”

Trump wishes he had a friend like that on the inside. Robert Mueller, who was appointed special counsel by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein after Trump fired then–FBI Director James Comey, is not that kind of prosecutor. The only way Trump could exert control over Mueller’s activities is by firing him. Thanks to Monday’s indictments, such a move would now be even more politically perilous for Trump.

There are aspects of Nixon’s downfall that Trump could take comfort in if he cared to study them. It seems clear, for instance, that the only reason Nixon’s presidency ended when it did is that, unlike now, there were enough Republicans in Congress who were willing to take on a president from their own party. But there should be nothing comforting to Trump in the story of Watergate’s first indictments. He’s in a much more precarious spot than Nixon was at that time, and he has much less hope than Nixon did of controlling the process going forward.