This piece was originally published on Just Security, an online forum for analysis of U.S. national security law and policy.

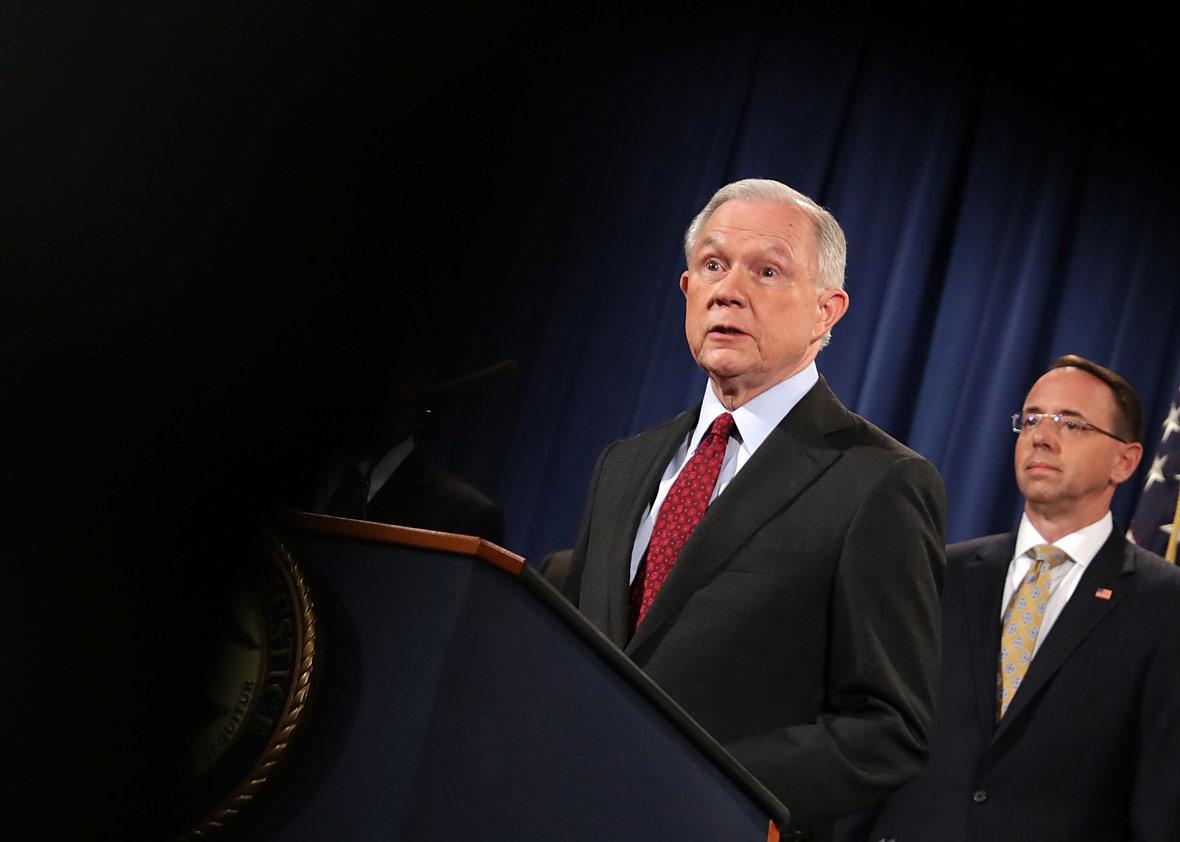

President Trump took to Twitter on Monday morning ostensibly to defend his “beleaguered” Attorney General Jeff Sessions, even though at least some of that beleaguerment is—thanks to last week’s New York Times interview (and potentially other behind-the-scenes machinations)—his own doing. If Sessions’ days as attorney general are indeed numbered, it’s worth gaming out the three very different scenarios for his succession atop the Justice Department, given their obvious potential implications for the ongoing investigation by Special Counsel Robert Mueller.

Want to listen to this article out loud? Hear it on Slate Voice.

Scenario 1: The DOJ Succession Statute and Executive Order

The most obvious and least controversial succession scenario would be for President Trump to follow the terms of the DOJ succession statute and his own executive order on DOJ succession, under both of which the deputy attorney general, Rod Rosenstein, would automatically become the acting attorney general pending the confirmation of Sessions’ successor. Of course, the downside from the president’s perspective would be to put Rosenstein (of whom he had such … geographically incorrect … critiques last week) in charge not just of overseeing the special counsel but of the entire department. And if the overarching goal here is more White House control over the Russia investigation, giving Rosenstein more authority doesn’t exactly seem consistent with that endgame.

Scenario 2: The Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998

A more complicated scenario would be to rely on the provision codified at 5 U.S. Code Section 3345(a)(2), which states: “notwithstanding [the default rule that the deputy becomes the acting], the President (and only the President) may direct a person who serves in an office for which appointment is required to be made by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to perform the functions and duties of the vacant office temporarily in an acting capacity subject to the time limitations of section 3346.”

In other words, the president may direct anyone who holds a “PAS” office—one requiring presidential appointment and Senate confirmation—to serve as acting attorney general for 210 days (and potentially longer, depending upon when the president nominates someone to the position). And under the terms of the Federal Vacancies Reform Act, the individual does not even have to be serving in the Justice Department at the time he or she is tapped to be acting attorney general; this person would just have to hold a Senate-confirmed position.

The upside of the Vacancies Reform Act route is obvious: President Trump could name someone as acting attorney general who is much more sympathetic to his views—someone who might take a far different view of Special Counsel Mueller’s investigation and who might even be inclined to seek to fire Mueller through one of the mechanisms I described in a post on the ACSblog on Friday. But there are downsides.

First, it is not at all clear that the language of the Vacancies Reform Act applies when the previous officeholder is fired. (The statute is triggered when the current officeholder “dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office.”) Indeed, there’s a nonfrivolous argument that this omission on Congress’s part was intentional—to prevent a president from firing an officer and then using the more generous provisions of the Vacancies Reform Act to hand-pick a short-term (and, potentially, un–re-confirmable) successor. Second, there is at least an argument that the specific terms of the DOJ succession statute (which clearly pass the mantle to the deputy attorney general, i.e., Rosenstein) should trump the more general terms of the Vacancies Reform Act. There’s a counterargument, of course—the Vacancies Reform Act is the later-enacted statute and so could be argued to override the DOJ statute—but there would at least be the prospect of a legal dispute. (For what it’s worth, the Justice Department’s own Office of Legal Counsel has concluded that the Vacancies Reform Act can override the DOJ succession statute.)

Third, and more pragmatically, as we learned with Noel Francisco and the solicitor general position earlier this year, the Vacancies Reform Act also constrains the ability of the person named to the “acting” position to be nominated as the permanent successor. So if President Trump has a long-term replacement in mind, even if he or she is already serving in a Senate-confirmed position, naming him or her as acting attorney general under the Vacancies Reform Act won’t work. In other words, the Vacancies Reform Act route, even if it’s available in a case in which the previous attorney general has been fired, is only a short-term solution (and one that disqualifies the short-term acting successor from being nominated for the position on a permanent basis). President Trump could name an unending series of short-term successors, but that assumes that there are enough already-serving PAS appointees willing to be used in this manner.

Scenario 3: The Recess Appointment Elephant in the Room

If the individual President Trump desires to serve as Sessions’ successor is Senate-confirmable, then nothing would stop President Trump from simply nominating the successor and naming someone else as the short-term acting attorney general under the Vacancies Reform Act. But on the assumption that the confirmation of a new attorney general would be conditioned by the Senate upon some promise of noninterference in the Russia investigation, it stands to reason that this option, while legally straightforward, may be off the table politically.

But now we come to the elephant in the room: President Trump’s power to “recess-appoint” Sessions’ successor. Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution empowers the president “to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.” And as the Supreme Court concluded three years ago in the Noel Canning case, “the Recess of the Senate” can include just about any formal recess that lasts 10 or more days—no matter whether it’s an intersession or intrasession recess—and the vacancy at issue need not arise during the recess. (Both these holdings were over the nominal dissents of four of the more conservative justices.)

So if the Senate recesses for 10 days or more in August (which currently appears to be at least a decent likelihood), President Trump could simply recess-appoint whoever he wants to serve as attorney general until the end of the next Senate session, i.e., Jan. 3, 2019. That person would have the same authority as a Senate-confirmed attorney general, which would likely include authority over the special counsel and the Russia investigation. Of course, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell could use the same tactics he used during the Obama administration to prevent a president from taking advantage of this power, but, well, I wouldn’t hold my breath.