Will marriage equality remain the law of the land in the United States? When the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution protects same-sex couples’ right to wed, its thundering decision seemed enduring and irrevocable. Yet just two years later, gay Americans’ marriage rights are once again under attack in conservative states—with the encouragement of some Supreme Court justices. It’s now clear that not all states, and certainly not all courts, view same-sex marriage as a settled issue. In fact, it’s increasingly apparent that marriage equality opponents have a long-term plan to roll back, and eventually reverse, the signature achievement of the U.S. gay rights movement.

To be sure, the Supreme Court’s 5–4 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges remains secure so long as its author, Justice Anthony Kennedy, remains on the court along with the four justices who joined his opinion. On June 26, in Pavan v. Smith, the court reaffirmed Obergefell’s core holding that states must extend all benefits and privileges of marriage to same-sex couples. But shortly thereafter, Kennedy retirement rumors resurfaced with a vengeance, this time with real substance attached: NPR’s Nina Totenberg reported that Kennedy had told law clerk applicants “he is considering retirement.” Above the Law’s David Lat then confirmed that Kennedy did, indeed, inform at least one applicant that he might retire at the end of next term. (That would be the summer of 2018.)

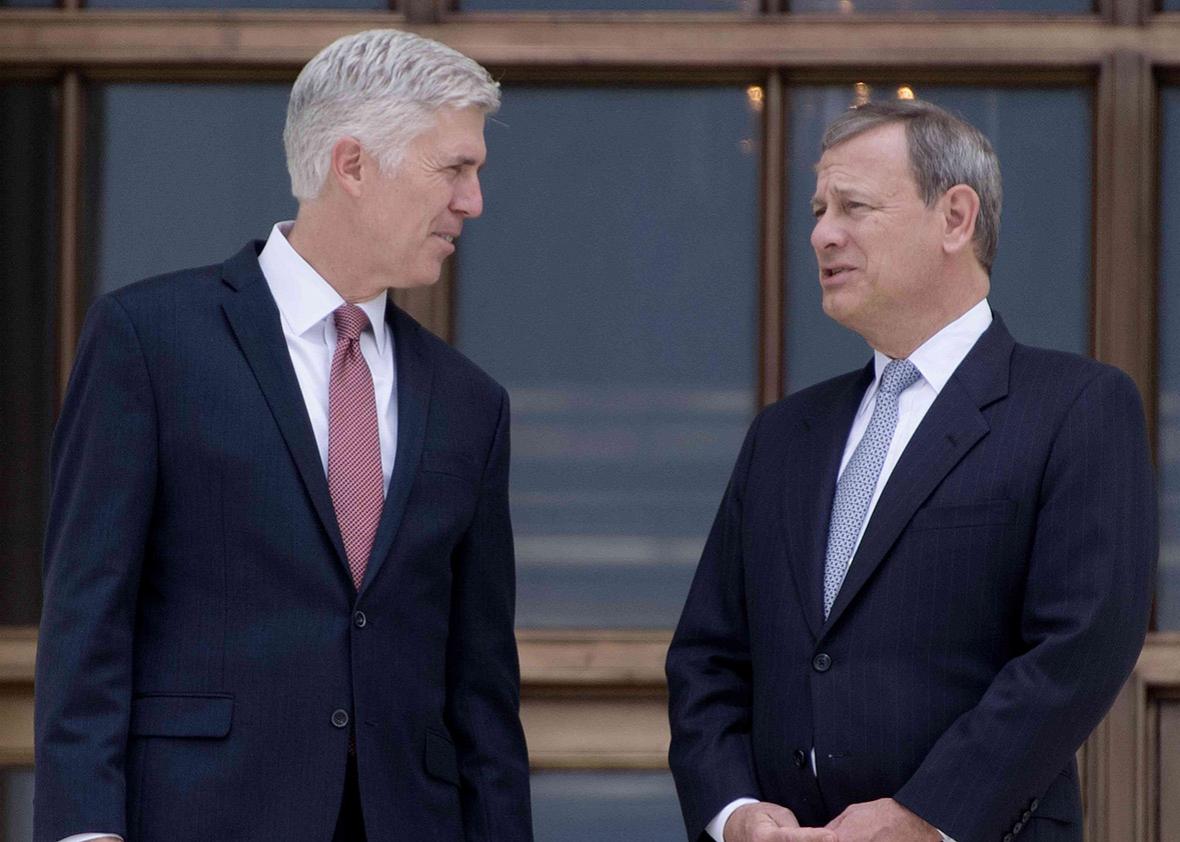

We should always take these rumors with a grain of salt, but I wouldn’t bet against Totenberg and Lat. At the very least, Kennedy is likely mulling retirement under Donald Trump and a Republican-controlled Senate. The consequences of Kennedy stepping down are difficult to overstate: Trump would likely replace him with a conservative hardliner like Justice Neil Gorsuch, creating a five-member bloc that could potentially demolish reproductive rights, voting rights, environmental protections, gun restrictions, and redistricting reform. No progressive victory enabled by Kennedy’s vote would be safe.

Marriage equality, and gay rights in general, will not be any different. Before Obergefell, some commentators (myself included) speculated that Chief Justice John Roberts might recognize the malice inherent in same-sex marriage bans and strike them down. We were wrong: Roberts’ Obergefell dissent was noxious and cruel, instructing same-sex couples not to “celebrate the Constitution” because it “had nothing to do with” the ruling. Roberts insisted that states may make same-sex partners legal strangers, prevent them from adopting their own children, and keep them off each other’s death certificates.

If Kennedy retires, Roberts will become the swing vote on marriage equality. It is difficult to imagine the chief justice supporting Obergefell in light of his previous dissent. An optimist might speculate that the chief justice, who cares deeply about the court’s institutional legitimacy, would uphold the decision as a matter of stare decisis. Roberts might reason that while he initially opposed Obergefell, he now has an obligation to follow it as a precedent of this court. Overturning the decision, after all, would throw same-sex couples into legal limbo. The ensuing chaos would not be a good look for the Roberts court.

But as the assault on Roe v. Wade has taught us, not all challenges to precedent must confront the original ruling head-on. Through sideways attacks, opponents can chip away at a decision until its foundation has been fatally undermined. Already, conservative states have launched two such attacks on Obergefell.

In the first of these efforts, Arkansas asserted that the Supreme Court’s same-sex marriage decision did not require the state to list married same-sex parents on their children’s birth certificates. This argument is plainly wrong: Obergefell compelled states to extend “the constellation of [marital] benefits” to same-sex couples, and mandated equal treatment on “birth and death certificates.” Arkansas already allows nonbiological heterosexual parents to be listed on their children’s birth certificates; for instance, when an opposite-sex couple adopts a child, they can obtain a new birth certificate that names them as the child’s parents. Moreover, Arkansas law provides a “presumption of legitimacy” to straight couples: When a married woman births a child, her husband is listed as the father on the birth certificate even if he is known not to be the biological father.

And yet, in late 2016, the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the state’s refusal to extend these privileges to same-sex couples. Its decision appeared to be a bad-faith misreading of Obergefell: A majority of the (elected) justices claimed, falsely, that birth certificates are a record of biology, not a benefit of marriage, and are therefore exempt from Obergefell’s command of equal treatment. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed that decision in Pavan v. Smith, explaining that birth certificates are, indeed, a benefit of marriage, and that married same-sex couples must therefore be listed on their children’s birth certificates.

Roberts did not explicitly dissent from that ruling, which was issued per curiam without a single author. That doesn’t necessarily mean that Roberts voted to bring Arkansas in line with Obergefell; he might have, but he may also have decided not to record his dissent in the opinion. His silence could mean that he accepts Obergefell—or it could mean nothing at all.

Gorsuch, on the other hand, did dissent, along with Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. The newest justice wrote that the Arkansas Supreme Court “did not in any way seek to defy but rather earnestly engage Obergefell”—a laughable contention given the lower court’s obvious desire to avoid compliance with that ruling. Gorsuch then maintained that Arkansas has “a birth registration regime based on biology” and “rational reasons” to exclude same-sex couples, another blatant fiction. Worst of all, Gorsuch alleged that gay Arkansans already had relief because the state had agreed to expand birth certificate rights to same-sex couples.

This last claim was simply wrong. Gorsuch may have been confused by the fact that late in litigation, the state attorney general conceded that Arkansas would list married lesbians on birth certificates if the birth mother used artificial insemination. But this concession leaves all other types of same-sex parents out in the cold and does not carry the force of law. As Michael C. Dorf notes at Take Care, it also requires the wives of birthmothers to jump through an extra hoop: They’d have to obtain a court order to be placed on their child’s birth certificate, whereas the husbands of women who conceive via artificial insemination would be automatically listed. And despite the attorney general’s concession, Arkansas’ primary birth certificate statute still excludes same-sex couples—a policy the state Supreme Court affirmed. So there’s no guarantee that judges would issue correct birth certificates to lesbian mothers. That’s why the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the statute to be applied in a way that encompasses same-sex couples.

Was Gorsuch genuinely baffled by the case? Was he intentionally muddying the waters? Who knows? Either way, his broader willingness to play along with Arkansas’ game sent a clear signal to other conservative states: If you want to defy Obergefell, my conservative colleagues and I are OK with that.

A few days later, the Texas Supreme Court signaled right back to Gorsuch that it was listening loud and clear. In a unanimous decision, the (elected) justices held that Obergefell does not clearly require states to extend spousal benefits to same-sex couples. Their bizarre decision approaches outright defiance of the U.S. Supreme Court. Spousal benefits, such as health insurance, obviously fall within “the constellation of benefits that the states have linked to marriage”—which under Obergefell, must be extended to same-sex couples. By pretending to believe otherwise, the Texas Supreme Court might as well have declared that it would not apply Obergefell at all.

The Texas justices were not quite as defiant as the Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Jefferson Hughes III, who announced in 2015 that he would never apply Obergefell because same-sex couples are child molesters (among other dubious reasons). But the result is largely the same: State supreme court justices are giving their governments the green light to resume discrimination against same-sex couples.

It’s easy to imagine many other ways that governments can purport to comply with Obergefell while quietly killing it with exceptions. So long as Kennedy stays on the court, these attempts to undermine the decision will fail. In Obergefell and its predecessor, United States v. Windsor, Kennedy wrote that the government may not “degrade” or “demean” same-sex couples by imposing “a separate status” or “stigma” upon them. This sweeping language should protect gay Americans so long as its author sits on the bench.

But what happens if Kennedy is replaced by a Gorsuch-style conservative? At that point, Roberts would be free to rewrite Windsor and Obergefell however he wants. Roberts could remain faithful to the original text of both decisions. He could also reverse them. But the likeliest possibility is that Roberts first cuts them down to a single guarantee—the right for same-sex couples to receive a marriage license with no attendant privileges. In case after case, Roberts could vote to allow discrimination against same-sex couples but affirm their right to the license itself. He could, for instance, permit the denial of spousal benefits to same-sex couples, contending that so long as gay people can marry, their rights have not been abridged. One by one, he could pluck the stars out of Obergefell’s “constellation of benefits,” while insisting that he respected the decision’s bottom line. And then, once Obergefell has been mostly gutted, Roberts could drop this pretense and deliver the final death blow, asserting that the decision had already been lethally eroded. It’s a classic Roberts trick.

Marriage equality is secure today. Obergefell will not fall tomorrow. But it is on shakier ground than most Americans probably realize. If Kennedy retires, the future of same-sex marriage will rest in the hands of a man who vehemently opposes gay rights. And nobody should count on the chief justice to uphold a decision he hates.