In early March, Anitere Flores, the second ranking Republican in the Florida state Senate, handed the NRA and its allies a stunning defeat. She said she would vote against a raft of bills proposed in committee that would have permitted carrying guns on college campuses, airports, school zones, and courthouses, among other places. The move ensured that those bills are dead for 2017 and will probably ruin Flores’ previously perfect rating from the National Rifle Association. Marion Hammer, former president of the NRA and the executive director of United Sportsmen of Florida, expressed shock in a letter to those groups’ members: “I cannot tell you why Sen. Flores suddenly turned on law-abiding gun owners because I do not know.”

But Sen. Flores explained why she put a halt to the legislative agenda of arguably the most successful and influential lobbying organization in the United States: redistricting.

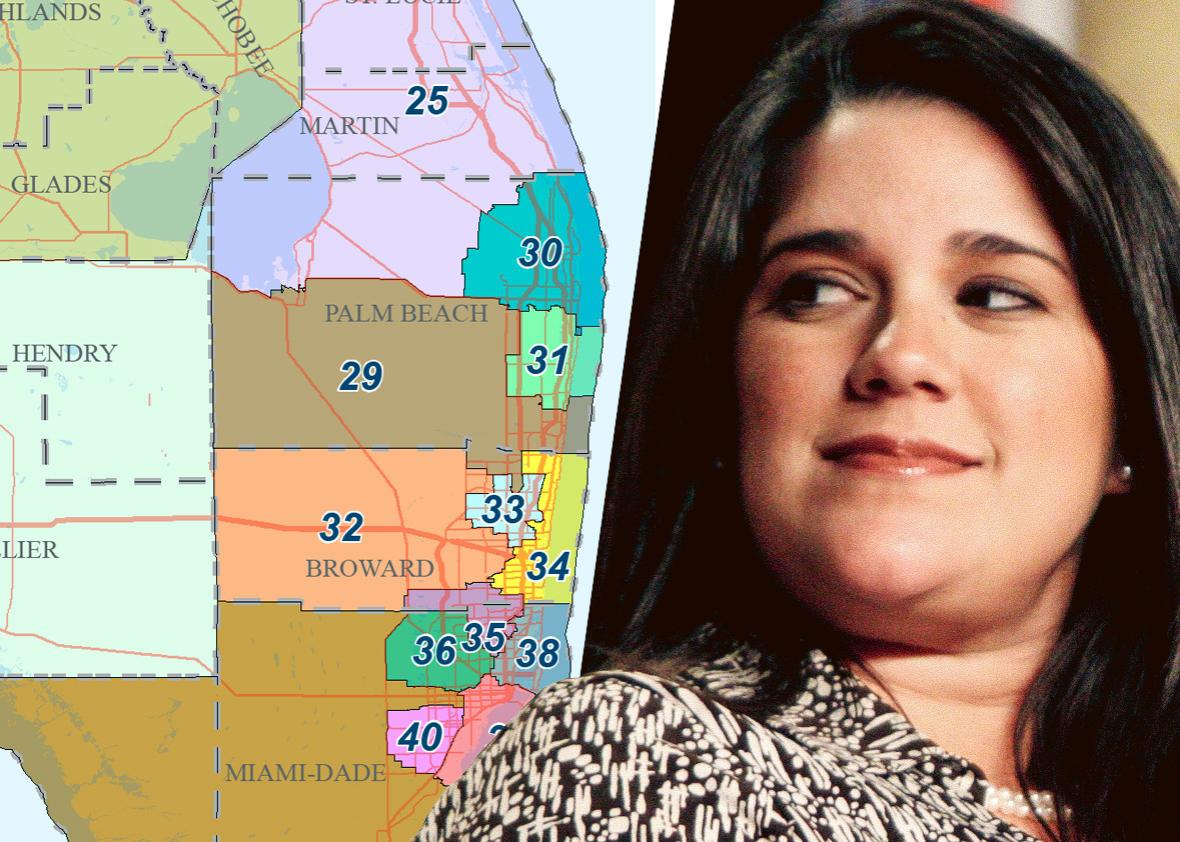

In 2010, Florida voters passed two amendments to the state’s constitution aimed at stopping state legislators from gerrymandering, or redrawing legislative district lines in ways that favor one political party over another or deprive racial and language minorities of equal opportunities to elect their candidates of choice. Although Obama won Florida’s electoral votes twice and the state has more registered Democrats than Republicans, gerrymandering has given Republicans outsize control of the state’s congressional delegation and state Legislature. But after years of litigation, in 2015 Florida courts held that the Republican-gerrymandered maps violated the two “Fair Districts” amendments and later adopted new congressional and state Senate maps for the 2016 elections (drawn by the League of Women Voters and other voting rights groups). The new map moved Flores from running unopposed in a safely Republican district into a Democratic-leaning district, where she won a contested election.

When asked about her surprising opposition to the recent right to carry bills, Sen. Flores cited the changed composition of her district: “The 2010 district was different than the 2012 district, and the 2012 district was different than the 2016 district, so it’s obviously very different. But my stance since I’ve been in the Senate on guns has been, I think, rather consistent, in that I reflect the majority of my constituents.” She went on to note that her “constituents in Miami-Dade and Monroe [counties] have been vocal in that this view reflects their opinion.”

In other words, redistricting doesn’t only affect which legislators are elected, but how they choose to govern.

For Flores, whose district was reorganized based on a nonpartisan map, this had the result of motivating her to respond to her constituents’ preferences over the agenda of a powerful special interest that has held sway in the Florida Republican Party.

But where districts are still drawn to maximize the electoral success of one political party, the opposite effect can be seen. North Carolina may be the Republicans’ most effective gerrymander. In 2008, Barack Obama won North Carolina’s electoral votes and Democrats won eight out of 13 of the state’s congressional seats. But in 2010, Republicans won majorities in both houses of the North Carolina state Legislature. They used their control to entrench substantial and durable Republican majorities in the state’s legislative offices.

Since Republicans enacted their redistricting plan, North Carolina has enacted what Richard Fausset, in September 2014 in the New York Times, described as “one of the most far-reaching conservative agendas in the country, passing a ‘flattened’ income tax that gives big breaks to the wealthy as well as new rules that limit access to voting, expand rights for gun owners and add restrictions for abortion providers.” Fausset’s assessments came a year and a half before the state enacted its attack on LGBTQ rights, the notorious “Bathroom Bill,” HB2. As state Sen. Jeff Jackson, a Charlotte-area Democrat, wrote earlier this month: “The 10 percent of the state that votes in the GOP primary has become the filter for all our legislation—to the point where they might as well be the entire electorate. It’s skewing the agenda.”

David Price, one of North Carolina’s three remaining Democratic congressmen, spoke with author David Daley for his excellent book Ratf**ked about the polarizing effects of the state’s gerrymandered map on his Republican colleagues: “It really affects the way members behave once they come [to Congress]. I’ve heard some guys say they might be more moderate, but they just can’t be. The rule of thumb becomes don’t let any opposition develop to the right. It all adds up to pretty extreme behavior. The gerrymandering really exacerbated that.”

We’ve also seen how gerrymandering has crept up to the national level. According to Daley, Price also said that “his Republican colleagues will sometimes admit, openly, that fear of a challenge from the right affects the way they vote and how willing they are to compromise. It’s part of what has made Congress so frozen and dysfunctional throughout the Obama years.”

Having had a front-row seat to the crippling effect that gerrymandering had on Congress during much of his presidency, Barack Obama and his former attorney general, Eric Holder, have committed to undoing the Republican stranglehold on redistricting. Their project, the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, is poised to start raising money to target key state legislative and governor’s races and to initiate litigation against maps that may violate the Constitution or the Voting Rights Act.

North Carolina is also grappling with the right way to redraw its districts, and bills have been introduced to state Legislature, though new maps won’t be drawn until 2021. “The political challenge will be finding support within the majority party in the state Senate,” Sen. Jackson wrote. “If we end gerrymandering, it will be the most important piece of legislation this decade.”

New maps will undoubtedly result in some new faces at the state capitol, but many incumbents will persevere through their re-election campaigns. And if Anitere Flores is any indication, voters may find that even if redistricting reform doesn’t change who they send to office, it’ll change for the better how they’ll govern when they get there.