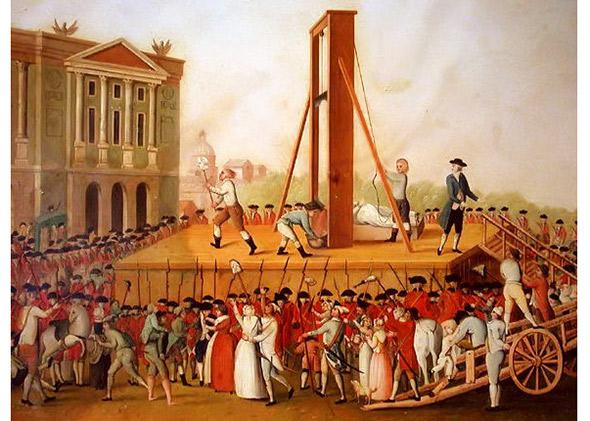

A nationwide shortage of a key ingredient used in lethal injections has led some states to experiment with new, untested drug cocktails for executing death row inmates. The practice has raised moral and constitutional questions, and unleashed a wave of litigation. At this point, as a society, we should be asking whether we can stand by and watch as this barbaric practice continues. Are these iffy drug combinations really any better than the guillotine?

Bringing back the guillotine may sound crazy, but it’s certainly better than the current alternative. It’s better for prisoners because quickly severing the head is believed to be one of the quickest, least painful ways to die. And it’s better for organ recipients because the bodies of guillotined prisoners could be more quickly harvested for viable parts, unlike organs that may become unusable after lethal injection due to hypoxemia.

To be clear, I find capital punishment abhorrent in theory and practice. Even if you believe the death penalty is morally acceptable, evidence of wrongful executions and the large number of inmates having been condemned to death before being exonerated shows its undeniable failings. But until the Supreme Court overturns precedents saying that state-sanctioned executions are not cruel and unusual punishment, shouldn’t we strive to make executions the most humane that they can possibly be? Lethal injection—the current method of execution of the federal government and the 32 states with the death penalty—and the guillotine are both evils, but the guillotine is the lesser evil of the two.

In the 2008 Baze v. Rees decision, a divided Supreme Court said lethal injection in particular does not violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. But writing for the dissent, Justices Ginsburg and Souter expressed grave concerns that the three-drug cocktail administered in Kentucky “would cause a conscious inmate to suffer excruciating pain.”

Dr. Jay Chapman, the creator of the three-drug cocktail, supports ditching his 1977 invention due to its reputation for causing slow, painful deaths. “The simplest thing I know of is the guillotine,” he told CNN in 2007. “And I’m not at all opposed to bringing it back. The person’s head is cut off and that’s the end of it.” Other doctors have stuck their necks out by protesting lethal injection on the grounds that administering it requires medical professionals to violate the Hippocratic Oath. The American Medical Association officially discourages physicians from participating in lethal injections.

The guillotine sidesteps any Hippocratic hypocrisy. The layman can operate a guillotine just as well as a doctor. As Hanni Hindi wrote in Slate some years ago, “The prisoner facing the guillotine was placed facedown on a large wooden plank, their head secured in a brace and steadied by an executioner’s assistant known as ‘the Photographer,’ who held onto their hair (or, in the case of bald prisoners, their ears). When everything was in place, a 120-pound blade was dropped from 7 feet in the air, immediately severing the prisoner’s head.” It never misses its mark.

The movement to bring back the guillotine has gained some limited traction in modern politics. In 1996, Georgia state legislator Doug Teper introduced a bill before the Georgia House of Representatives that would have amended the state’s death penalty code to provide for death by guillotine instead of the electric chair. “The General Assembly finds that while prisoners condemned to death may wish to donate one or more of their organs for transplant, any such desire is thwarted by the fact that electrocution makes all such organs unsuitable for transplant.” Teper’s bill died in the House. But given the swirling controversy over questionable lethal injection ingredients, perhaps the issue is now ready to be placed in the court of public opinion.

One familiar position put forth by advocates of lethal injection is that the three-drug cocktail is far less offensive than the guillotine—to witnesses. Some state laws grant victims’ families the right to view executions. Would bringing back the guillotine fail to consider the feelings of those who would have to watch someone get his head severed?

In short, no. As Michael Lawrence Goodwin argues, there are two main reasons why victims’ families watch executions: out of a desire to represent a murdered family member at what they consider the ultimate stage of criminal justice, and because of a need for closure. A guillotine execution would not devalue someone’s symbolic presence, and it may actually better facilitate closure for certain witnesses.

Goodwin’s analysis shows that for some families, the notion of closure may create a sense of false hope, and watching an execution may actually “revictimize” them. On the other hand, some families who have witnessed an execution have subsequently complained that the executed died too easily—that they “got off light.” In the former cases, no execution method would satisfy the witness. But the guillotine may provide succor in the latter cases. Even if it’s quick and painless in fact, it’d be hard to imagine the guillotine failing to instill a sense of justified wrath.

Those who would be up for watching a state-sanctioned beheading should heed the warning of Albert Camus. The author and philosopher once told a biographer the story of his father’s experience witnessing the guillotine in action: “He got up in the dark to go to the place of execution at the other end of town amid a great crowd of people. What he saw that morning he never told anyone. My mother relates merely that he came rushing home, his face distorted, refused to talk, lay down for a moment on the bed, and suddenly began to vomit.”

As Camus made clear, capital punishment is always a barbaric practice. If we’re going to continue to allow it in the United States, maybe it makes sense to be confronted by how gruesome it really is.