Today, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, a case that could be a sequel to 2010’s Citizens United. While Citizens United dismantled restrictions on “independent expenditures” by corporations and unions—eventually giving rise to the super PAC—McCutcheon questions the restrictions Congress imposed on individual donations to political candidates themselves each election cycle. At the moment, you can give a total of $5,200 per candidate for each two-year congressional election cycle (plus more for PACs and parties), up to $48,600 total for all the candidates you want to support. Shaun McCutcheon, the Alabama businessman who is the plaintiff here, wants to be able to give to as many candidates (and PACs and party groups) as he chooses. In deciding his case, the court will have an opportunity to revisit Buckley v. Valeo, the crucial 1976 ruling that struck down limits on campaign spending, but placed restrictions on contributions out of concern for the “reality and appearance of corruption.”

Citizens United dismissed the problem of corruption, and split the court 5–4, pitting the conservatives against the liberals. McCutcheon may well do the same. But Citizens United wasn’t a strictly partisan affair: While most progressives derided it as a catastrophe for political corruption, some on the left praised it as a triumph for the First Amendment. We asked three of the liberals who backed the conservative majority in Citizens United how they felt about it two years later—and what they make of McCutcheon.

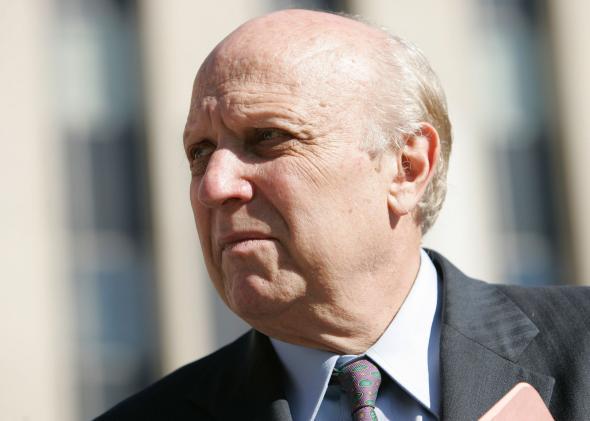

Floyd Abrams, frequent Supreme Court advocate and First Amendment litigator, who vociferously championed the Citizens United decision:

I don’t see McCutcheon as being a very hard case. I also don’t see it as being at all as important as Citizens United from a First Amendment perspective unless the court uses it as a stepping stone towards reversing or significantly revising Buckley itself.

From my perspective, if one assumes the constitutionality of contribution limits (and of treating such limits as constitutionally different in kind from expenditure limits) the issue in McCutcheon becomes whether any cognizable societal interest is served by allowing contributions, in whatever amount Congress has determined is appropriate, to x candidates but not x plus one, or two, or many. I think it’s hard to defend the proposition, even on a rational basis level, that if Congress has determined that contributing a certain limited sum to candidates does not corrupt the system that making that contribution to a longer list of candidates does. I’ll grant that the effect of allowing contributions in certain maximum amounts to more candidates could be said to lead to more dependence by more candidates on the relatively few individuals who have that sort of money and choose to contribute it. But, of course, the other way to view that is that every additional contribution will lead to more speech and that speech about elections is about as protected as any under the First Amendment. So once again, we return to the nature of the debate about Citizens United itself, although in an area where Congress has already determined that contributions in certain amounts are not by their nature (or amount) corrupting.

There remains, of course, the question of the “appearance” of corruption. I have always found that to be an especially unpersuasive and troubling basis to overcome First Amendment interests so from my perspective that’s a non-starter. In any event, though, I don’t see that there’s a worse “appearance” if one makes contributions, up to maximum amounts fixed by Congress, to more rather than fewer candidates.

As for Citizens United itself, I’m not the best one to answer how it’s faring because my involvement in the case and my support of the court’s ruling has never been based on my judgment about the on-the-ground impact of the ruling. I’m for letting Nazis speak, letting film makers film the torture of animals, letting video games be sold to all and the like not because I think society will be “better” if the speech is allowed but because we will be less free if it is not.

We followed up to ask about the problem of “bundling.” As Rick Hasen explains:

A member of Congress, for example, would be able ask for a single $3.6 million contribution (through a “joint fundraising committee”—essentially an arrangement to take a check to be disbursed to more than one campaign) to distribute to all federal congressional candidates and to national and local political parties. He or she could keep from that check only $5,200 ($2,600 for the primary and another $2,600 for the general election), but the parties and PACs could then use the passed-on funds to run ads attacking his or her opponent. As a big bundler, this member of Congress would have great influence over other members. And, of course, the $3.6 million donor would have the most influence of all.

Abrams wrote back:

My basic response is that ads attacking candidates for public office are protected by—are you ready?—the First Amendment so Rick’s visage of more such speech is not especially terrifying to me. Of course, the members of Congress that can direct funds to others tend to have more clout than others, just as they do now. And big donors may well get in front of the line of those who want to speak with and potentially persuade members of Congress, a quite similar result to that occasioned by allowing them to make expenditures supporting candidates. To me, the basic question is nothing more or less than how seriously one takes the First Amendment in this area. I don’t think the campaign finance “reformers” take it seriously at all.

Lawrence Tribe, professor of constitutional law at Harvard University, who struck a nuanced and ambivalent tone with regard to Citizens United:

The reason you’ve not seen me quoted about McCutcheon is that I’m holding my fire both on that new case and on Citizens United for my forthcoming book (with Joshua Matz), which is coming out next June.

Kathleen Sullivan, a litigator and professor at Stanford Law School, who cautiously praised the result in Citizens United, didn’t respond to our emails and calls today. We’ll add her comments if we hear back from her.