Attorney General Eric Holder understands the biggest problem with America’s criminal justice system is that we lock up far too many people for far too many years. And he’s willing to take real steps, with or without Congress, to systematically change federal prosecutions to shorten sentences and reduce prison populations.

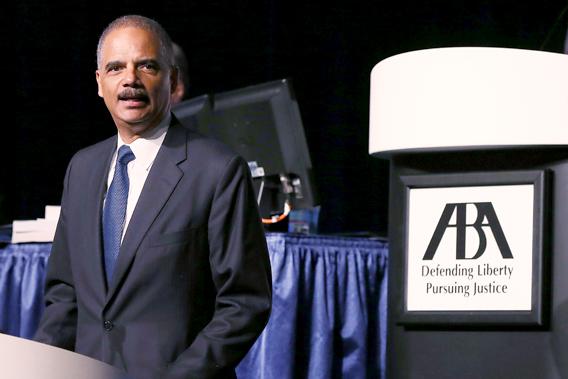

That’s the message of his speech to the American Bar Association today, which the Justice Department gave a big rollout. How far his reforms will actually go depends on specifics Holder hasn’t outlined yet, and also on all of the individual federal prosecutors’ offices around the country and how they interpret the boss’s directive.

Holder started his ABA speech by declaring, “it’s well past time” to be “considering a fundamentally new approach.” He singled out the war on drugs for rethinking, in light of these truly depressing facts:

“As a nation, we are coldly efficient in our incarceration efforts. While the entire U.S. population has increased by about a third since 1980, the federal prison population has grown at an astonishing rate—by almost 800 percent. It’s still growing—despite the fact that federal prisons are operating at nearly 40 percent above capacity. Even though this country comprises just 5 percent of the world’s population, we incarcerate almost a quarter of the world’s prisoners. More than 219,000 federal inmates are currently behind bars. Almost half of them are serving time for drug-related crimes, and many have substance use disorders.”

Holder also pointed to research released in February showing that “black male offenders have received sentences nearly 20 percent longer than those imposed on white males convicted of similar crimes.” He called this “shameful.”

OK, so what can the Justice Department, on its own, do about all of this? Holder’s main fix involves centralizing a particular facet of prosecutorial discretion that has giant consequences for how long drug offenders spend in prison. As Charles Savage explains in the New York Times, Holder is telling prosecutors not to specify the quantity of drugs they are charging for certain categories of defendants, about which more below. If prosecutors don’t list the amount of drugs, then the indictment won’t trigger the attendant mandatory minimum sentence upon conviction. For example, if you carried 5 kilograms of cocaine, you’d normally be under the gun for a 10-year mandatory sentence. Without the amount specified in the indictment, you could be sentenced to far less. Or not. Your sentence will now be up to the judge, who can take into account the 5 kilograms if he or she wants. It just won’t be automatic.

Holder says he’s making this change because some mandatory minimum statutes “generate unfairly long sentences,” and “have had a destabilizing effect on particular communities, largely poor and of color,” which means they are “ultimately counterproductive.” He says the defendants his new policy will help are “certain low-level, nonviolent drug offenders who have no ties to large-scale organizations, gangs, or cartels. They now will be charged with offenses for which the accompanying sentences are better suited to their individual conduct, rather than excessive prison terms more appropriate for violent criminals or drug kingpins.”

There are all kinds of research and common-sense support for Holder’s position that mandatory minimums have run amok. As he points out, he is following in the footsteps of red and blue states that are already trying to make the war on drugs less draconian, mostly because they’re tired of pissing money away. (In 2010, the country spent a total of $80 billion on incarceration.) But is the attorney general in effect proposing to veto an act of Congress, which after all enacted the mandatory minimums? You could argue that he’s violating the spirit of the mandatory minimums by telling prosecutors to leave out key facts. But when I asked a bunch of law professors if they saw it that way, they all said no. Think of it this way: Prosecutors always have discretion over which crimes to charge. They’re looking at a menu of statutes. They can pick the one that means they’re throwing the book at you, or not. In some cases, they already don’t indict in a way that triggers a mandatory minimum. Maybe they agree with Holder that low-level offenders don’t deserve it. Or maybe they’re not sure they can prove the necessary drug quantity.

Holder’s policy is not a new law: He’s the boss, so the U.S. attorneys around the country are supposed to do what he says, but if they don’t, they’re not lawbreakers.

The experts I consulted said that the attorney general is merely centralizing the decision-making that already occurs. There’s a recent precedent: In 2003, under President George W. Bush, former Attorney General John Ashcroft directed all federal prosecutors to charge the “most serious, readily provable offense” available. In other words, Ashcroft too recognized that prosecutors have choices at charging, and he told them to go with the biggest crime they can make stick without too much trouble. Then as now, the idea is to rein in disparities, so that like offenders receive like sentences. (Though the research showing that black men do more time than other defendants who commit the same crimes suggests that it hasn’t quite worked out that way.) The difference between Holder and Ashcroft is that he’s moving the needle of prosecutorial discretion in the direction of mercy rather than stiffer punishment.

I’m left with a different question about Holder’s announcement: How big a shift does it actually represent? Let’s go back to his description of the kind of defendants who may now escape an automatic mandatory minimum: nonviolent drug offenders without ties to big gangs or cartels. According to the Times article previewing the speech, a DoJ memo being sent to all U.S. attorney offices decrees that the defendants they’re supposed to save from mandatory minimums must have no “significant criminal history.” That phrase has a particular meaning in federal sentencing law, and it’s not reassuring. If you have a marijuana possession in your past, or you got caught jumping a turnstile a couple of times, you have a significant criminal history. In other words, it doesn’t take much. Also, how many drug offenders really have no ties at all to big gangs or cartels, since they all have to get their product from somewhere?

I should note, though, that the phrase “significant criminal history” didn’t actually show up in Holder’s speech. Did he decide in the end to leave it off his list of criteria? I asked a DoJ spokesperson and didn’t get a clear answer. But if only nonviolent defendants without links to big operations or significant criminal histories are off the hook of mandatory minimums, that may not mean much, practically speaking. Federal sentencing law already includes a “safety valve” that allows judges not to impose mandatory minimums for the class of offenders Holder may have in mind. Here’s hoping that when Holder spells out the details of Monday’s announcement, he’ll expand the group of defenders to be spared harsh mandatory minimum penalties.

And here’s another even fonder hope: that Holder’s pledge to fix the federal system will also translate into leaving Colorado and Washington state alone while they try their hand at legalizing marijuana. So far, the attorney general has been silent. We’ve got this, from a spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office in Colorado on election night last November, when Colorado and Washington made it legal to possess small amounts of pot. “The Department of Justice’s enforcement of the Controlled Substances Act remains unchanged.”

If Holder shifts his position on weed, he’ll take heat from plenty of law-and-order types, including some of the country’s former drug czars. Before the November election, they said that legalizing marijuana posed a threat to public health and safety and presented a “danger that touches every one of us.” On the other side is the craziness of how much money and manpower the country spends sending marijuana growers and dealers to prison. Take a look at this paper from Brookings, which calls for the Obama administration to “hammer out clear, contractual cooperation agreements so that state-regulated marijuana businesses will know what they can and cannot safely do.”

Oh, and also, there’s the problem of racial disparity: According to federal data crunched in a report by he ACLU in June, African-Americans are almost four times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than white people, even though blacks and whites use the drug at similar rates. That degree of bias is just as shameful as the sentencing discrepancies Holder pointed to Monday. He should make it his next cause. It’s true that a decision not to enforce federal drug laws in Colorado and Washington is different from the decision about how to enforce mandatory minimums that Holder announced Monday. A truce on pot would obviously be a much bigger deal. But hey, maybe the attorney general is ready to go on a roll.