President-elect Donald Trump has made the securing of our southern border and the expulsion of undocumented immigrants from our country the foundation of his inaugural policies. In his first 100 days in office, he plans to launch the largest expulsion of undocumented immigrants in our nation’s history—between 2 and 3 million immigrants.

Expelling this many people may sound logistically impossible, but efforts on this scale have been undertaken before, as Trump well knows. During the Republican primary debates, he referred to President Eisenhower’s Operation Wetback, which deported an estimated 1.1 million undocumented migrants in 1954: “ ‘I like Ike,’ right? The expression. ‘I like Ike.’ Moved a million-and-a-half illegal immigrants out of this country, moved them just beyond the border. They came back. Moved them again beyond the border, they came back. Didn’t like it. Moved them way south. They never came back.”

This casual description of the program belies a misunderstanding of what it actually accomplished—and why we would never want it to happen again. Operation Wetback was not simply the enforcement of immigration laws but a campaign of fear against immigrants. Its goal was to draw lines between who was and who was not American.

Operation Wetback was launched just as the racial underpinnings of our immigration policies began to be removed. Two years earlier, in 1952, our immigration laws had been changed so that, for the first time since our nation’s founding, being white was not a legal prerequisite for naturalization. Operation Wetback’s enforcement approach—assuming those who were not white had dubious citizenship—reflected the Immigration and Naturalization Service’s (and many Americans’) resistance to this legal shift.

In 1953, INS commissioner Argyle Mackey complained of “the human tide of ‘wetbacks’ ” as the “most serious enforcement problem of the Service.” The first Mexican guest workers had come to the fields legally through the World War II braceros program, a series of laws and diplomatic agreements that allowed Mexicans to work on American farms. Mackey wrote, in the official INS house organ, that the reports of good work in the States to “the Mexicans left at home … turned the trickle into the flood” and for “every agricultural laborer admitted legally, four aliens were apprehended.” Willard Kelly, the assistant commissioner of the border patrol, called this “the greatest peacetime invasion ever complacently suffered by any country.” These concerns led the INS to launch, in 1954, what was officially called the “Special Mobile Force Operation,” or as it was actually referred to in the INS and in the American media, “Operation Wetback.”

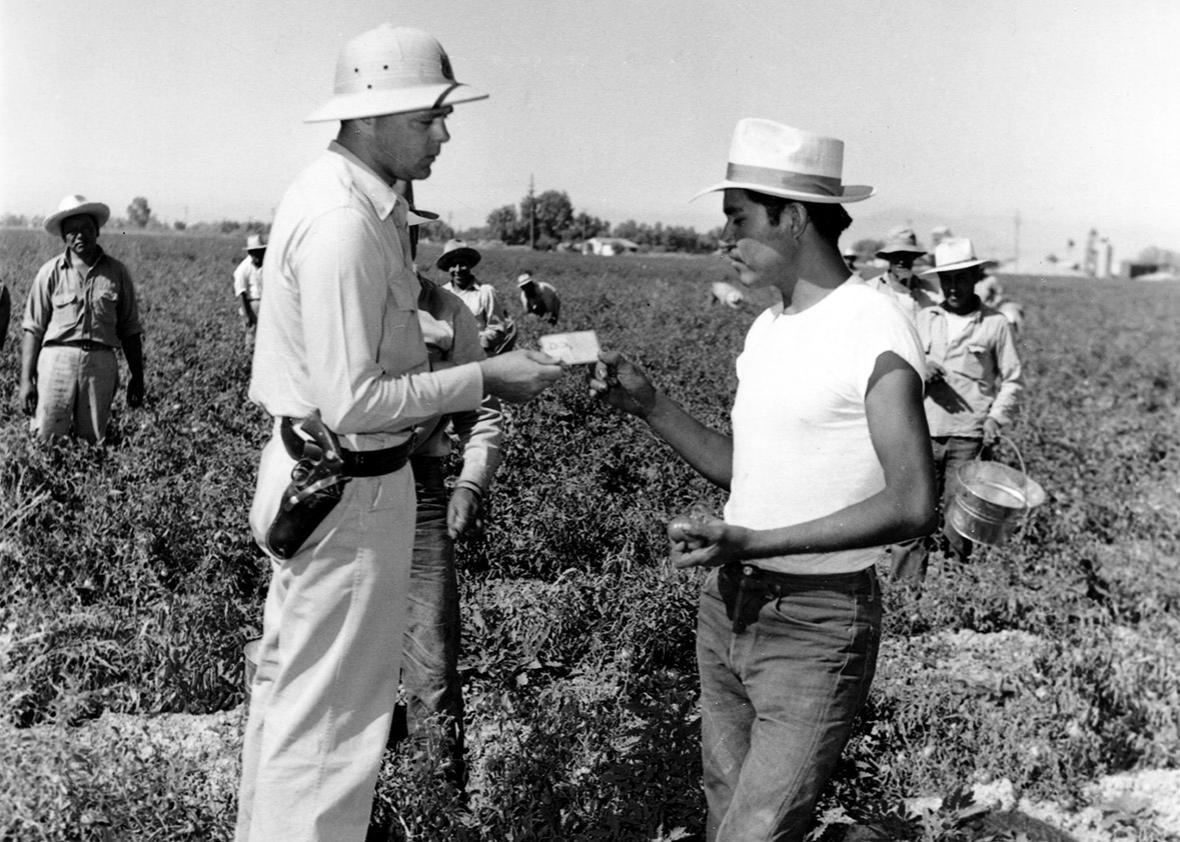

The most powerful agents for Operation Wetback were not in the border patrol but in the press corps. The operation, from its beginning, was a public relations campaign, as close to Trump’s preferred medium—reality television—as was possible in the 1950s. Embedded in the border patrol crews that conducted raids throughout California and Texas, journalists wrote stories praising the professionalism of the “squads swooping down in surprise visits to farms, industrial plants, business and factories,” as the Los Angeles Times put it. Major news outlets ran tallies of the number of “wetback captures” and noted the telephone tips flooding the switchboards at INS. Alongside these pieces, outlets ran photos, like those that appeared in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, of border patrol agents in crisp uniforms and helmets reviewing maps as they planned out their operations and of immigration officers and sheriff’s deputies rounding up Mexican immigrants at the factories and farms where they worked. The INS celebrated the success of the program publicly. Papers also ran photos of apprehended men held in crude holding pens set up in city parks and in the parking lots of processing centers, of men marched as captives through border towns, of men packed onto charter buses and of lines of those buses waiting to cross the border. In movie theaters across the nations newsreels showed Mexican immigrants rounded up and made to stand in the hot sun as their bodies and their belongings were searched.

What the newsreels didn’t show were those same detainees, now with shaved heads, crammed onto trains or trucks bound for the middle of the desert, where they were left 15 miles across the Texas border on the highway. A leader with the largest Mexican labor organization (Confederación de Trabajadores de México) described the transportation of these deportees as being like “truckloads of cows.” In one instance, near Mexicali, across the California border, 88 deportees died of exposure in the 112-degree heat. Others—about a quarter of those deported—were shipped to Mexico by boats from Port Isabel, Texas. Congressional investigators, historian Mae Ngai has written, likened the boats “to an ‘eighteenth century slave ship.’ ” The press coverage also failed to capture the many instances in which immigrants were roughed up, detained, and summarily deported without due process, often with no chance to notify their families that they had been swept up in raids on factories, fields, boarding houses, and even the same movie theaters that showed the newsreels. Mexican Americans had to prove that they belonged. INS agents dismissed the legitimacy of draft cards or Social Security cards, insisting on birth certificates, which few people carried around on their person. Mexican Americans who couldn’t produce birth certificates quickly enough were deported.

The effectiveness of Operation Wetback in terms of actual numbers of deportations is unclear. The INS reported that it deported 1.1 million migrants in 1954. But many were deported before the campaign even began, and others were apprehended multiple times, sometimes within a single day. A year later, the INS triumphantly reported that the “so-called ‘wetback’ problem no longer exists.” In 1955, “less than 250,000” migrants were deported. An INS statistician could confidently write that, thanks to the efforts of 1954 and ’55, “the southern border has been secured.” Officials congratulated themselves on turning back the “invasion,” declaring that the jobs the deported had been doing would be filled by unemployed Americans.

Even as the border patrol forces were carrying out raids, however, the New York Times reported that the director of the INS, Joseph Swing, was holding a “series of cordial meetings” with growers throughout the Southwest, assuring them they would receive the bracero permits they needed to keep their farms staffed. Such permits doubled in 1954. Growers could now hire Mexicans who had been working on their farms illegally. In the parlance of the time, these new bracero slots allowed farmers to “dry out their wetbacks.”

Even the official end of the bracero program in 1964 did not bring a surge in demand for American agricultural workers. Farms mechanized instead of hiring. Undocumented workers, like the rest of the American workforce, continued the shift from farms to cities, and in the years after Operation Wetback and braceros, undocumented migrants filled other roles in the American economy, as they continue to do today.

Targeting such a vast workforce today will not just affect the deportees but the most basic operations of our economy. No matter how you measure Operation Wetback’s “success,” its campaign of terror undeniably had a negative impact on American life, one that affected small businesses as much as it did immigrants. Garment factories, foundries, hotels, and restaurants reported a rise in absenteeism as their employees stayed at home rather than risking apprehension at work. The unofficial policy of the INS was to starve the immigrant out: “We’ll see if they can stay home as long as we can keep checking on them,” said the director of the immigration service in Los Angeles. With their workers in hiding, newspapers reported that businesses in that city and in cities throughout the Southwest suffered a blow in the summer of 1954.

Americans, of course, can reasonably disagree over the appropriate levels of immigration. But we should not disagree on the humanity of migrants—or of our own citizens. If the mass deportations begin as Trump has promised, the citizenship of Latinos will always be questioned. Latinos, along with people who look Latino to law enforcement, will be forced to produce their citizenship documents on a regular basis to avoid detention or deportation. They will live in a poisonous atmosphere of constant suspicion, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other law enforcement will, inevitably, make tragic mistakes. Children will not be exempt. Trump has already announced that on his first day he will be revoking the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which allows children and young adults with uncertain status to remain in this country and in school.

To return to the era of Operation Wetback would be to return to an America ruled not by law but by terror. We will not strengthen our economy by persecuting the most vulnerable. Launching a massive deportation drive will not preserve jobs for American workers. What it will do is draw racial borders around our citizenry and restore whiteness as a necessary condition for being a real American.