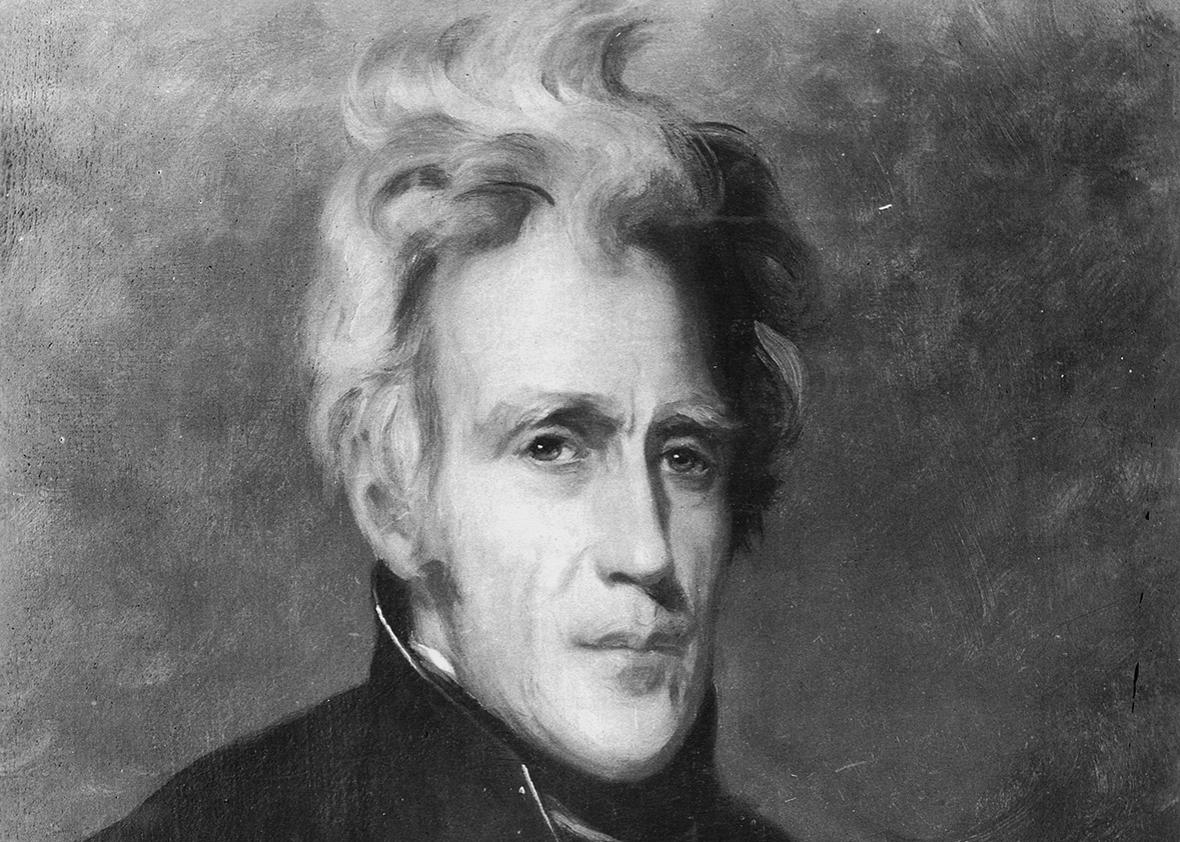

In the wake of the Treasury Department’s announcement last week that Harriet Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson on the front of the $20 bill, Sen. Jim Webb (D-Va.) wrote an editorial defending Jackson in the Washington Post. “Far too many of our important discussions are being debated emotionally, without full regard for historical facts,” Webb argued. Glossing the issue of Indian Removal, Webb ended a paragraph excusing Jackson’s actions toward Native Americans with this salvo: “It would be difficult to call someone genocidal when years before, after one bloody fight, he brought an orphaned Native American baby from the battlefield to his home in Tennessee and raised him as his son.”

Jackson named this “son” Lyncoya (sometimes spelled “Lincoyer”). A monument to his short life, near the site of the lopsided 1813 battle that claimed the lives of most of the people in his village, shows how defenders of Jackson have long used Lyncoya to finesse Jackson’s historical reputation in relationship to Native Americans. The monument reads, in part:

At this site … Gen. Andrew Jackson found a dead Creek Indian woman embracing her living infant son. … Because of his compassion, Gen. Jackson took the infant to Fort Struther … where he nursed him back to health. Gen. Jackson then took the baby to his family home, the Hermitage, in Nashville, Tennessee, where he and his wife Rachel named the child Lincoyer and adopted, raised, loved, and educated him as their son.

Why would Jackson, who made war on the Native tribes of the Southeast for decades, and was instrumental in their removal to Indian Territory, “adopt, raise, love, and educate” a Creek orphan? Jackson was famously orphaned himself, during the Revolutionary War, at the age of 14. Does this seemingly compassionate act really reveal some kind of buried altruism toward Native people, as Webb would have us believe?

I spoke with historian Dawn Peterson, who gave me a preview of the Lyncoya chapter in her forthcoming book, Indians in the National Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion, which will be published by Harvard University Press in 2017. Peterson’s book looks at different kinds of adoption of Native people during the early years of the republic, between about 1790 and 1830. In bringing Lyncoya into his family, Jackson joined other Southern slaveholders, Indian agents, and Northern Quakers in a short-lived, but politically potent, tradition of assimilative adoption. In the South, Peterson told me, slaveholders adopted Native children while “imagining they were assimilating Native people and their lands into the confines of the United States. They believed that what they were doing was a benevolent act, but also understood it as a form of cultural genocide.” Reading Peterson’s work, it became clear that Jackson might have had many reasons—emotional, political, and ideological—to bring Lyncoya home to the Hermitage.

Lyncoya was a child of the Red Sticks—a faction of traditionalist Creeks, mostly from the northwestern, or “Upper,” towns of the Creek Confederacy, that was determined to resist white encroachment. In 1813, the Upper Creeks went to war with the Lower Creeks, who were attempting to retain their sovereignty by assimilating; allying; and, in some cases, intermarrying with Euro-American settlers. In August 1813, the Red Sticks killed 250 Creek and Euro-American settlers on the plantation of Samuel Mims, in present-day Alabama. Then major general of the Tennessee militia, Jackson saw this intratribal conflict, and the public opprobrium leveled at the Red Sticks in the wake of the Fort Mims killings, as weaknesses he could exploit in his ongoing quest to force Creek lands into Anglo hands. The battle that killed Lyncoya’s village was part of this quest.

The Battle of Tallushatchee was beyond bloody. A thousand American soldiers, led by John Coffee (a Jackson ally who was married to his wife Rachel’s niece), circled Tallushatchee, a Red Stick village, the morning of Nov. 3, 1813, and killed systematically, until all 186 men in the village were dead. Historian Robert Remini flatly calls Tallushatchee “a massacre” and quotes Lt. Richard Keith Call, who described the scene: “We found as many as eight or ten dead bodies in a single cabin. … Some of the cabins had taken fire, and half consumed human bodies were seen amidst the smoking ruins. In other instances dogs had torn and feasted on the mangled bodies of their masters.” The soldiers took 84 captives, including Lyncoya.

Intervening biographers (and engravers of monuments) have taken Jackson at his word when he reported, in a letter to Rachel, that Lyncoya’s “own female matrons wanted to k[ill him] because the whole race & family of his [blood] was destroyed.” Dawn Peterson questions how deeply Jackson would have been able to investigate Lyncoya’s actual status, given the chaotic state of the village after the slaughter. Whether or not this report was a misunderstanding, Peterson argues, the idea that Lyncoya was in danger of death emerged out of Jackson’s own skewed perceptions about Native traditions of matrilineality and his beliefs that Native family structures were inferior to his own. Jackson himself—a Southern patriarch and head of a “better” kind of family unit—could be flexible enough to rescue a boy from his own relatives’ benighted hands.

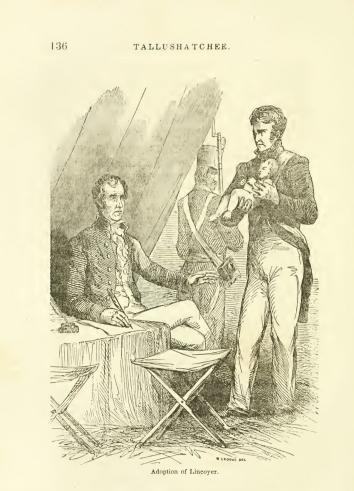

Jackson, who wasn’t able to have biological children with Rachel, brought several white wards into his family over the years, including Andrew Jackson Jr., a nephew on Rachel’s side whose parents gave him over to the Jacksons’ care soon after his birth. Jackson intended Lyncoya as a gift for Andrew Jr., who was 5 years old at the time of the Battle of Tallushatchee. Writing to Rachel in its aftermath, he told her: “I send on a little Indian boy for Andrew to Huntsville—with a request to Colo. Pope to take care of him untill he is sent on—all his family is destroyed.” (Here, Jackson’s passive voice neatly hides the author of this destruction.)

“Adoption” meant different things, legally and culturally, to early 19th-century Americans than it does to us. (Massachusetts didn’t pass the first adoption law in the country until 1851.) Peterson writes that people used the term in many different contexts, and when applied to Native children, it had political implications. “There’s a lot of people [in the early 19th century] who use the language of incorporation, who temporarily house and educate [Native children],” Peterson told me. “But they’re imagining it as part of a larger adoption project, which is the assimilation of Indian people, having them adopt U.S. culture and values. They’re also eventually thinking of [Indians] as adoptable into the U.S. national family. They’re conceiving of the body politic itself as a family.”

In Lyncoya’s case, it’s not clear what status Jackson meant the boy to have within his plantation “family” of white wards and enslaved Africans. The gifting of Lyncoya, Peterson writes, has uneasy parallels in the way that Southern slaveholders like Jackson would give black children to their family members. But Lyncoya wasn’t a slave—not quite. Jackson told Rachel to keep Lyncoya in the house, rather than giving him lodging with the enslaved people at the Hermitage. Jackson called Lyncoya a “pett”—a diversion for Andrew Jr., who would wield some kind of undefined power over the 4-years-younger child.

Andrew Jr.’s role in Lyncoya’s life was meant to be, in its own way, patriarchal. So Jackson wrote to Rachel: “I send [Lyncoya] to my little Andrew, and I hope he will adopt him as one of the family.” The next year, he repeated this gift with Creek boys he gave to Andrew Jackson Donelson and Andrew Jackson Hutchings, two wards of deceased friends who had bequeathed their children to Andrew and Rachel Jackson. All three young Andrew Jacksons in his household, the elder Jackson pronounced, would have their Creek “petts”—Native counterparts who would divert them and teach them mastery.

Peterson told me that white adopters of young Native Americans in the American South were following Thomas Jefferson’s ideas about the influence of environment and the improvability of Native people. By bringing young Creek boys into his household, Jackson was making an implicit argument about the power of whiteness. The environment of a properly arranged plantation household would be capable of bending a Creek child toward whiteness, even if it could not uplift an equivalent black child (Africans being, according to Jefferson, “lower” than Natives). Looked at from this angle, Lyncoya was a living argument for the supremacy of the white way of life. Jackson killed Creek people, took Creek land, and raised their children as his own—a primal act of domination.

Lyncoya was also politically valuable to Jackson. Jackson described himself as feeling an “unusual sympathy” for the boy, writing to Rachel: “Charity and Christianity [said] that [Lyncoya] ought to be taken care of. He may have been given to me for some Valuable purpose.” This “sympathy” indicated an affinity Jackson felt for a fellow orphan. John Henry Eaton, a friend and early biographer of Jackson, made the connection explicit in 1817, pointing to Jackson’s early life, which was marred by the loss of his entire immediate family during the Revolutionary War:

He has ever since manifested the liveliest zeal towards it [Lyncoya] prompted by benevolence, and because its fate bore a strong resemblance to his own, who, in early life, and from the ravages of war, was left in the world, forlorn and wretched, without friends, or near relations.

Peterson thinks that Lyncoya’s presence at the Hermitage was another way for Jackson to remind the world of his self-made, orphaned status, while reinforcing the idea that the adult Jackson was a man of charity. She points to an inquiry Jackson made of Tennessee Sen. George Washington Campbell in 1816, asking whether the senator might speak of Jackson’s tutelage of Lyncoya in Congress. Lawmakers hearing of Lyncoya’s education might temper their belief that Jackson was an inflexible killer of all Native people and thief of their lands.

During Lyncoya’s life, Andrew Jackson’s wars changed everything for the Creek and for the other Indian tribes of the Southeast. Creek slaveholding elites who tried assimilation as a strategy to retain their land and sovereignty would find that the strategy did not work. In the Treaty of Fort Jackson, these Lower Creeks, who had allied with the Europeans, were not given any preference in the negotiations to end the Creek Wars. Jackson took their lands anyway.

As fortunes changed for the worse for the Creek, Lyncoya received an education from the same tutors who taught the young Andrew Jacksons. For a while, the elder Jackson hoped to promote him in society, writing to Rachel in 1823 that he wanted “to exhibit” the 11-year-old to “Mr. Monroe & the Secretary of War” in hopes that they might allow him to enter West Point. But sometime between 1824 and 1828, he was apprenticed to a saddle-maker—a path much different from West Point. Lyncoya died at the Hermitage in 1828, at age 16, of tuberculosis.

We don’t know why Lyncoya’s life shifted course in its last few years. In her book, Peterson suggests that the educated Indian—the Creek polished by the perfection of Jackson’s domestic arrangements—became a less appealing figure, as public opinion swung toward believing that Native people were noble, doomed savages who could not assimilate but must be moved West to make way for progress. There was also the danger that the well-educated Lyncoya might transform into a Creek slaveholder—a class then causing trouble for white politicians arguing that the only path for Indians in the Southeast was removal.

I asked Peterson what she thought of people such as Webb using Lyncoya as a counterpoint to balance Jackson’s historical reputation. Pointing to historian Michael Paul Rogin’s book Fathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the American Indian, Peterson told me, “One of the arguments in that book is, as long as Indians behaved in a way that Jackson is amenable to, he’s fine with them. If you’re a ‘good Indian,’ which basically means you do everything Jackson wants you to do, he’s cool with you, and then if you’re a ‘bad Indian,’ then there’s no mercy.” There’s little room to find magnanimity in this interpretation. “Was he out to willy-nilly exterminate the Indian population and kill every Indian he sees?” Peterson asks, rhetorically. “He’s not the Texas ranger, who would say ‘the only good Indian is a dead Indian.’ … But it’s really hard to make the argument that he’s somehow magnanimous.”

“I think Lyncoya is very much about him understanding himself as a good person, as opposed to him actually really wanting to support indigenous sovereignty or even indigenous life more broadly,” Peterson said. “As the Trail of Tears shows us, Jackson couldn’t care less if Indian people starved to death on the way to Indian Territory. I think it’s safe to say he had a blatant disregard for indigenous people.” For Peterson, the “saving” of one orphan of war can’t absolve Jackson from his actions. “I think it’s part of this impulse to say, ‘Look, I’m not a monster, even though I’ve done these horrific, horrible things. On an individual level I can tolerate Indian people.’ As opposed to admitting, ‘Everything I’ve done has been at the disservice of Indian people.’ ”