This article is adapted from The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast.

It’s the time of year when Americans remember a gritty story of conquest and death by decking their houses in warm fall colors and loading their plates with fattening food. Noting that Thanksgiving myths paper over the violent invasion of the continent is hardly news; few contemporary Americans are unaware of the triumphalism stuffed in their turkeys. Even retailers seem a little squeamish about the holiday’s dark origins, as Thanksgiving-themed packaging now tends to favor harvest imagery rather than pilgrims and American Indians.

The iconography of Plymouth Rock and First Thanksgiving was invented in the 19th century, when scenes of colonial beginnings were a common subject for painters. Today, Americans’ unease around the holiday’s history has turned the subject of first contact into a cartoonist’s cliché. Artists now use the native perspective to set up jokes about contemporary politics: Indians call the newcomers “illegal immigrants” or “gentrifiers.” A recent New Yorker take on this trope showed Wampanoags turning away a Mayflower landing party with the caption: “Sorry, this is a private beach.”

For historians interested in the true story of how English-speakers came to dominate American shores, these images that reappear every November reveal common misconceptions. Cartoonish visions of the European arrival do not just obscure what happened, they distort where it happened. Renderings often zero in on the moment when foreign feet touched the continent. Artists depict Indians as passive and land-bound while showing the English as active and seaborne. And they take it for granted that land was the only source and setting of conflicts.

But first encounters did not always take place on soil. Contrary to those pictures that strand them on beaches, Indians met colonists as fellow mariners. In many parts of colonial America, coastal waters became a frontier, a simultaneously destructive and creative space between cultures. Early conflicts typically began offshore. Natives and newcomers clashed over coastal access and maritime resources including shell beads and whale oil. And though you might reasonably assume that the disparity between European and Indian technologies was the greatest on the water, in fact it would be a long time before colonizers had a clear advantage over the people they hoped to colonize.

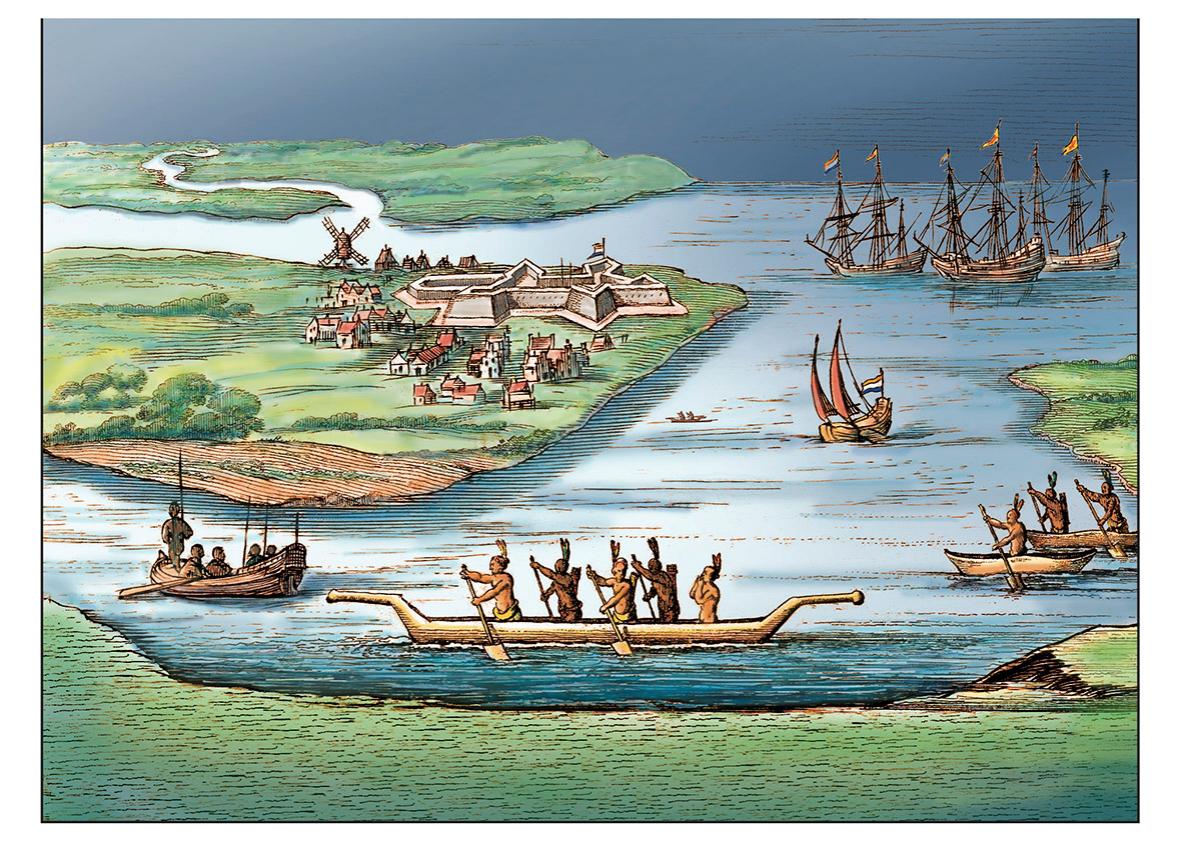

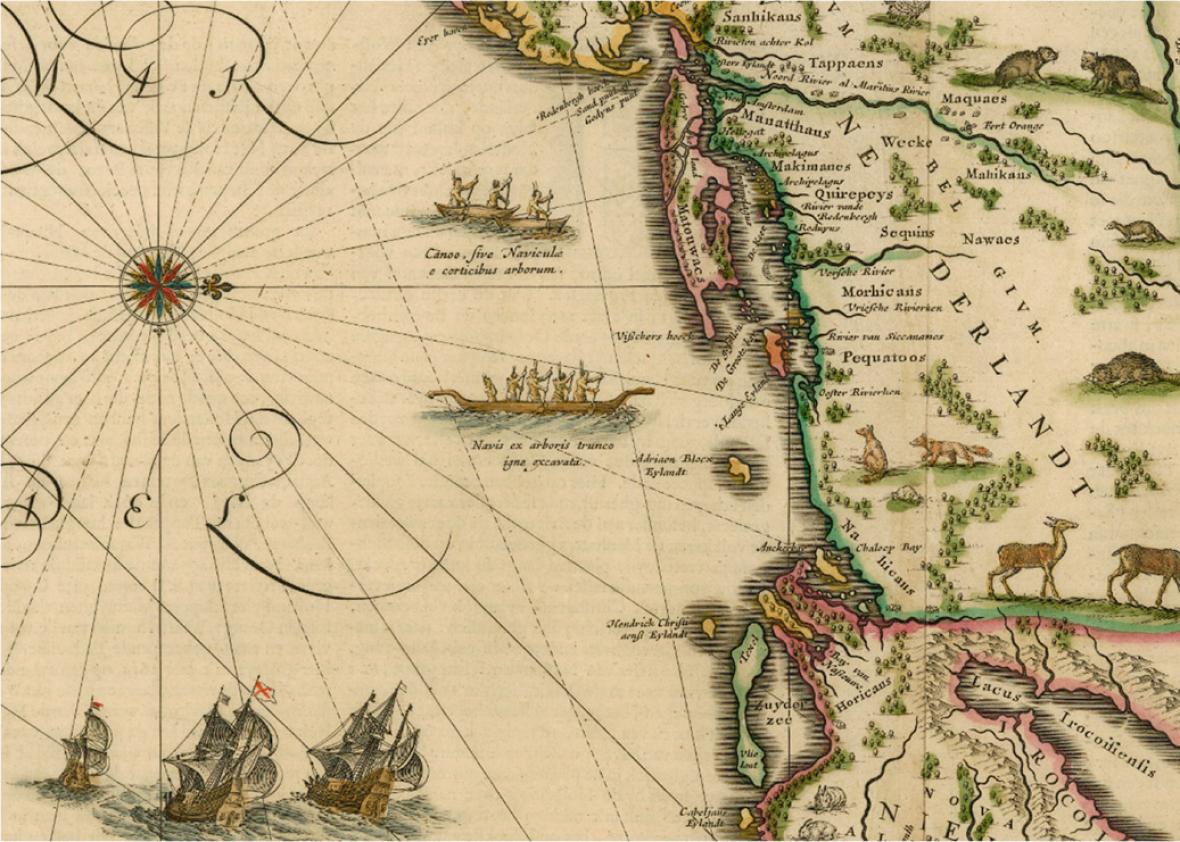

One of the most hotly contested saltwater frontiers was found between the Hudson River and Cape Cod. Tens of thousands of Algonquian-speaking people had long made their homes along this sandy margin. After years of brief visits to these waters, English and Dutch colonists built their first settlements—Plymouth and New Amsterdam—at the eastern and western ends of the coast in the 1620s. They eventually converged along Long Island Sound as the century wore on.

Unlike later artists, European invaders seldom ignored or trivialized native seafarers. The fleets of indigenous boats that boldly came up alongside alien craft were seldom the light bark canoes commonly associated with American Indians. Rather they were heavy, narrow vessels carved from the trunks of mature trees, stretching an average of 20 to 30 feet long.

Dugout canoe replicas.

Courtesy of Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center.

It is now easier to picture these dugouts thanks to boatbuilders from the Mashpee Wampanoag nation. Using their ancestors’ traditional burn-and-scrape methods, they have built a small fleet of these boats, known as mishoon, hosted mostly at the Plymouth Plantation museum in Massachusetts. They finished their largest mishoon yet this summer with help from the Mashantucket Pequot Museum in Connecticut. Named Nookumuhs, or “our grandmother” in the Pequot language, the newest vessel took her maiden voyage down the Mystic River estuary this August with a crew of 12.

In the 17th century, when these shores were thick with towering old-growth trees, Natives made even larger mishoon, which the colonist Roger Williams reported easily held “twenty, thirty, forty men.” Another newcomer claimed he witnessed a sea canoe with 80 people aboard plowing through the waters of Long Island Sound. Indians also built light bark canoes for protected passages, but most coastal Algonquians preferred dugouts when heading into offshore waters. Crews sometimes raised “poles in their Conoos” that the English likened to the “masts in our boats,” rigged with small sails that Narragansetts called sepâkehig. Williams noted that Indians had been sailing long before the colonial arrival, writing that “their owne reason hath taught them” how to sail canoes on downwind courses of 30 miles or more.

Courtesy of the Pilgrim Hall Museum

Though Native vessels were simple when compared to European ones, that fact only made foreigners all the more impressed with Algonquians’ nautical prowess. Colonists were astonished at the oarsmen who “will venture to Seas, when an English Shallope dare not bear a knot of sayle; scudding over the overgrown waves as fast as a winde-driven ship.” “They will indure an incredible great Sea,” wrote another, who described indigenous vessels “mounting upon the working billows like a piece of Corke.” When colonists looked for “skilful hands to guide them in rough weather, none but the Indians scarce dare to undertake it.”

Newcomers also prized Natives’ geographic knowledge. Early English traders valued Indians’ advice over “the opinion of our best Sea-men of these times,” for they “understood the Natives themselves to be exact Pilots for that Coast, having been accustomed to frequent the same, both as Fishermen and in passing along the shoare to seek their enemies.” The explorer Thomas Dermer was grateful to the Wampanoag mapmaker who alerted him to the existence of Long Island when he “drew mee a Plot with Chalke upon a Chest, whereby I found it a great Iland, parted the two Seas.”

This kind of detailed information was so precious that colonists resorted to kidnapping nearly 50 Natives from the region in the years from 1600 to 1620, the year the Mayflower first dropped anchor off Cape Cod. These enslaved men steered the invaders’ ships clear of shoals and led them to profitable harbors. As interpreters they gave the foreigners a simple vocabulary in their local dialect that was roughly intelligible across much of the shore.

One of the most extraordinary captives was a Wampanoag man named Epenow who was taken to London but convinced his captors to carry him back to his home island of Capawock (Martha’s Vineyard) with fanciful stories of gold, only to escape almost as soon they arrived. Years later, an English trader met the freed Epenow, who “laughed at his own escape, and reported the story of it” with obvious satisfaction. His tale was not unique—several other captives also escaped, tricked, or attacked their captors. Sailors who might have assumed Indians would be dumbstruck at their towering rigs soon discovered that their hostages could see the vulnerabilities of their vessels, and the weaknesses of their souls, quite clearly.

Aside from those dozens of Algonquian men forced to work as pilots, many more were willing ferrymen. As Europeans established their initial footholds, they regularly hitched rides in dugouts. Some foreigners were understandably hesitant to ride in the locals’ tippy boats, where “the edge was not more than a hand’s-breadth above the water,” but the advantage of riding with Indians was obvious. In one case, taking a canoe instead of walking from one village to another on Long Island “made full three hours difference.”

Canoe travel could also seem rather daunting to Europeans given that most of them, sailors included, could not swim. Remembering a few perilous sea voyages with his Narragansett neighbors, Williams wrote “it hath pleased God to make them many times the instruments of my preservation.” Once when he “questioned safety” one of his native friends reassured him by saying, “Feare not, if we be overset I will carry you safe to Land.” The man soothing his white-knuckled passenger hints that to Indian mariners, Europeans could sometimes seem like unseaworthy companions.

A few settlers even began to wonder if natives had in fact crossed the ocean before them, and their rugged sea-canoes were relics from the classical or medieval world. Thomas Morton observed that his Massachusett neighbors had eight points of sail and saw the North Star as part of a bear-shaped constellation, just like European seamen. Weighing these clues, Morton speculated they might be the descendants of “scattered Trojans” who had gone to sea and been caught in “a storme that would carry them out of sight of Land … and so might be put upon this Coast.” The Dutch colonial governor Willem Kieft believed in an alternate theory that his American neighbors “draw their Line from Iceland,” suggesting that coastal Indians were the descendants of Vikings.

Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University

Practical concerns made colonists appreciate native craft more than any historical speculations. Deliveries from these indigenous cargo vessels laden with furs and surplus crops kept the early colonies afloat. Canoes also connected colonial towns. Over the 17th century, English and Dutch correspondents frequently hired Indian messengers to carry their correspondence in the holds of their dugouts. Letters between the English living along Long Island Sound often named the Algonquian postmen who regularly travelled over 50 miles across the bay, even in the dead of winter. Dutch colonists along the Hudson also kept tally of payments given to native couriers in wampum (native sacred shell beads that doubled as currency) or gunpowder.

Native-style craft were so obviously useful that colonists eventually started building their own dugouts of identical size and form as Indian ones. Indian boatbuilding practices were cheaper and easier to master than European methods—and the shortage of qualified shipwrights in the region meant that plank-built vessels were pricier than most houses. Colonists therefore relied on simpler canoes for transporting goods, people, and livestock. The Dutch even boasted that they possessed a massive “wooden canoe obtained from the Indians, which will easily carry two hundred schepels of wheat”—a capacity of 9,000 pounds.

The exchange of vessels went in both directions. Fishermen visiting American waters sometimes sold their small sailing boats to Wabanaki people in the Gulf of Maine. Later explorers who were unaware of the practice were surprised to spot European craft entirely crewed by Natives. Incidents of colonists willfully surrendering their expensive boats were rather rare, but lending their larger, more complex vessels could be useful for cementing wartime alliances. Williams granted his Narragansett allies “use of my boats or pinnace” during the 1637 Pequot War; the Dutch also lent their sloops to their Indian partners in the midst of armed conflicts in the 1640s.

Much of the early frontier fighting in the Northeast actually took place on water. From their first encounters the Dutch and English were wary of hostile canoemen who “would kill the traders for the sake of the plunder.” Indians started attacking Dutch ships from the very first visit of Henry Hudson’s yacht De Halve Maen (The Half Moon) in 1609 and mounted ever more sophisticated and daring raids on Pieter Fransen’s ship Vosje (Little Fox) in 1613 and Hendrick Christiaensen’s ship De Swarte Beer (The Black Bear) in 1619. An Englishman sailing off Long Island in 1661 accidently hired his own murderer as a pilot. Rather than show the way, the Native navigator “struck his hatchet into [the colonist’s] head for his goods sake.” Similarly, a party of indigenous pirates “murdered and pillaged the saylers” in a bark stranded off Nantucket in 1665.

Sometimes these Algonquian buccaneers seized whole vessels. Raritans attempted to seize a Dutch trading yacht off Staten Island in 1641 and almost succeeded before a sudden squall allowed the traders to escape. In 1667, one William Weeks anchored off Naushon Island near Martha’s Vineyard only to find that the local Wampanoag people had their eyes on his 15-ton shallop and everything in it. The islanders let Weeks go unharmed but kept his craft and its cargo. It was unclear if Weeks ever recovered his property or if the islanders kept sailing their prize for years to come.

English colonists saw Indian naval attacks as justification for launching wars of conquest. Their casus belli for the 1637 Pequot War were two lethal raids on English vessels in 1634 and 1636. In the latter incident, the Manisses Indians who killed the trader John Oldham actually held onto Oldham’s sailboat for over a month until the colonists redeemed it. The war itself began as a series of estuarine engagements between colonial vessels and indigenous canoes. The English were so frustrated at their inability to win a single coastal battle that they changed tactics, sneaking inland to surprise their enemy with the infamous massacre of 400 Pequot villagers in May 1637.

Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Waterborne violence also escalated between the Dutch and Natives. When the Dutch director Willem Kieft provoked a war with Indians near Manhattan in the 1640s, both sides mounted amphibious attacks much like those of the Pequot War. In the 1650s and 1660s, Esopus Indians from the mid–Hudson Valley made such persistent and unrelenting assaults on Dutch vessels along the river that colonial officials sent soldiers in small craft to “constantly cruise from one side of the river to the other … especially at night, to prevent the coming down of their canoes, or at least to discover them.” The Dutch soon started capturing Esopus pirates and forcing them to serve as pilots. As the century wore on, both English and Dutch leaders across the shore started passing laws that regulated canoe traffic and explicitly forbade the selling of European craft to Indians.

In the largest war of indigenous resistance in the region—best known as “King Philip’s War”—saltwater quite became a frontier in the oldest sense of the word, meaning a regulated boundary between peoples. As fighting started in June 1675, Plymouth began policing its southern coast with daily patrols looking for war canoes. Weeks later, Rhode Island forbid Indians to travel by canoes without permission. New York first banned canoe travel across Long Island Sound, then ordered all Natives on the island to surrender their guns and dugouts, as both were obviously tools of war. Early campaigns against “King Philip” (the English name for the Wampanoag leader Metacom) also focused on scuttling his fleet of dugouts

Historians often describe King Philip’s War as Natives’ last attempt to “drive colonists back into the sea.” That common summary of indigenous motives ignores the fact that the English victory ultimately pushed Indians, not colonists, into the deep. During the fighting, hundreds of Native captives were sold as slaves on distant tropical islands and in European cities, joining the larger diaspora of Indians across the Atlantic rim. While the shores of New England and New York ceased being a military front between Natives and their neighbors by the late 17th century, it remained a shared cultural space and economic resource for years to come.

Many surviving Algonquian men turned to whaling as a living. Colonists had long dreamed of forming a shore-based whalefishery, but they were mostly unsuccessful until they started employing Indians around the year 1670. Indigenous sea hunters’ skills and their communities’ economic desperation were the single biggest factors in American whaling’s rapid half-century transformation “from an idea into a major force in colonial life,” in the words of author Eric Jay Dolan. As the populations of right whales in the Northeast began to crash in the 1730s and 1740s, white captains and their Native crews kept chasing whales further offshore. The industry was revolutionized when Nantucket shipbuilders invented onboard furnaces called tryworks in the 1750s that allowed crews to process whale oil without coming ashore and to seek out a wider variety of whale species. This innovation, born out of the necessity of the region’s depleted fishery, soon made New Englanders and New Yorkers (and their heavily Algonquian crews) the most enterprising and far-ranging whalers in the world.

Though whaling could be ruthlessly exploitative of both their bodies and the sea itself, many Native men found a degree of cultural buoyancy in this line of work. Besides allowing them to keep traditional roles as hunters and fishermen, whaling pushed Native men to become acquainted with a changing watery world. As Indian communities formed links to the port towns of New York, Sag Harbor, New London, Newport, New Bedford, Nantucket, and Boston, they often intermarried with freed and enslaved black people, forming enduring multiracial families that are the core of the modern tribal communities along this shore. A few of these seasoned travelers would become well-known on both sides of the ocean during the Revolutionary era and early republic for their advocacy of Christianity, Native rights, and the abolition of slavery.

Ultimately, viewing saltwater as a primary stage of cultural encounters changes our simple narratives of colonization, as the sea could never quite be won or lost. Entering the Atlantic economy would transform coastal native societies, but those natives would likewise alter the history of the larger ocean. Despite the physical perils of engaging with ships that carried horrific diseases and hostile invaders, coastal peoples did not retreat from the surf. At the same moment that Europeans stood awestruck at the green continent stretching before them, Indians faced an expanding blue horizon.