The first thing to say, when reviewing the question of what America should do about those of its citizens who advocate the murder of random numbers of its civilians, is that it is flat-out astonishing to see the debate being conducted at all. Faced with jeering, sniggering, vicious saboteurs who hide from the daylight and pop up on blogs and cheap CDs, calmly awarding religious permission for the capricious taking of life, what do we imagine Vladimir Putin would do? Or the police and security forces of the People’s Republic of China? Or Israel or Saudi Arabia? To ask the question is to answer it.

The United States happens also to be almost uniquely generous in conferring citizenship: making it available to all those who draw their first breath within its borders. For comparison purposes, try looking up what it takes for a person of Turkish origin born in Germany to become a citizen of the Federal Republic, or what is involved for a subject of the British “Commonwealth” in establishing that he or she has the right of residence in the United Kingdom. (In the waning days of British Hong Kong, there were actually British travel documents that did not give the bearer the right to reside in Britain.)

The appeal of the so-called universal jihad is in any case a call to abandon all national allegiance and instead identify only with the umma, or community of believers, so that at the outset we are confronted with the ugly idea of dual loyalty. Or perhaps of non-loyalty, disloyalty or—give it another name—treason.

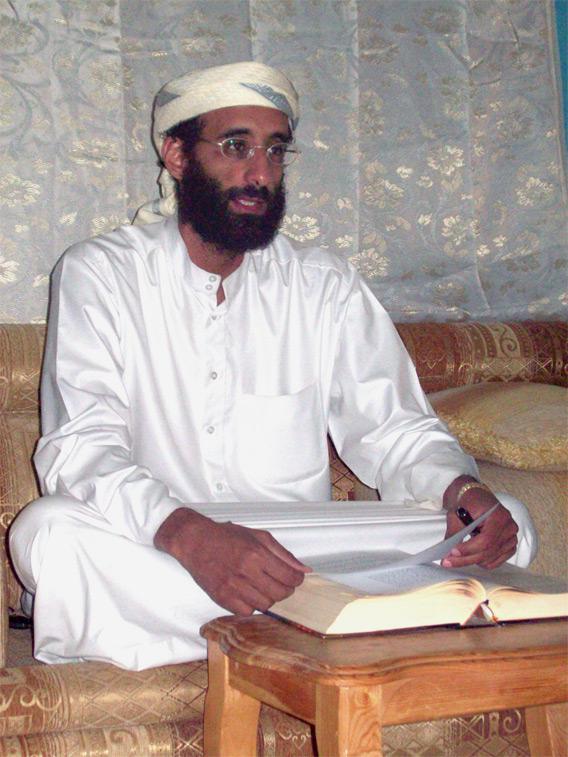

Those who oppose the inclusion of people like the late Anwar al-Awlaki on what we shudderingly do not call a kill list have correctly cited the passage in the Constitution that prohibits the authorities from inflicting the penalty of death, and many other penalties, without “due process of law.” So far, very little has been done to dispel the opacity that surrounds this concept as applied in this case. A judge has ruled that Awlaki’s father, backed by various civil liberty groups but otherwise appearing only in his own name, lacked standing to bring a suit against the death sentence that had been pronounced in advance by the Obama administration. It was stipulated that Awlaki Junior would have to appear and claim the many rights that go with American citizenship. (It has also been noted that a Yemeni court was asking Awlaki to explain his doings in that country: another opportunity of which he did not avail himself.)

Just as most precedents for controversy about citizens joining foreign armies or insurgencies come from the British “Foreign Enlistment Act,” so the best precedent that I can find, in the world where treason meets broadcasting, is a celebrated one from World War II. During that conflict, a man named William Joyce was employed by Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda to make continuous appeals to the British people to surrender. At other times, he went among British prisoners of war, attempting mostly in vain to recruit them to a “British Free Corps” that would fight under the colors of the swastika. He actually became rather a popular entertainment item in Britain, his arrogant drawling tones earning him the nickname “Lord Haw Haw.”

Captured in 1945 and hit with three counts of high treason, he pleaded that he was and always had been an American, and thus owed no duty of loyalty to the British Crown. This defense at first seemed a plausible one. But then one of the British prosecutors at Nuremburg, Sir Hartley Shawcross, discovered that on one occasion, seeking to move countries in something of a hurry, Joyce had applied for a passport to the British consulate in New York. In the minds of the judges, this was enough to establish that he had a duty of allegiance to the Crown. He was duly hanged, leaving behind a slight impression that Shawcross had won on points, even if slightly tricky ones.

One possible way of approaching the whole question of due process might be to re-examine the question of citizenship. After all, Awlaki went further than any Nazi propagandist, telling his readers and listeners (and some specific later perpetrators) that they were at liberty to kill any Americans, any time, anywhere. The evidence is that he carefully walked at least one perpetrator—Maj. Nidal Hassan of Fort Hood—through all the stages that supposedly qualified him to declare lethal holy war on his colleagues. Lord Haw Haw never got anywhere near that far. For Awlaki to continue to claim that he wants to be numbered among us (the target population, after all) is a bit rich, to put it mildly. Instead of the pretzel shapes of casuistry into which the Justice Department seems to be contorting itself in the search for a justification, why may we not lawfully strip him and those like him of their right to call themselves American, and of the protections and privileges that accrue?

We do not seem to know whether Awlaki’s father was acting for his son when he petitioned the court, but from now on it would become necessary for the younger man or rather his emulators to plead his own case, perhaps even by proxy, and have the nerve to do so. He should have to show good cause why he did not choose to appear in person, and if that alibi happened to be the brute fact of his having fled all known jurisdictions, it would tend to tell against him. (Of course, he could always have the courage to renounce his citizenship.) Precedent would be set for any would-be emulators: You have been amply warned that this very tolerant and conscientious society has strict limits to its patience. Such a hearing would fall short of an ideal definition of due process, but only to the precise extent that the defendant had already put himself outside the law. One of the Obama administration’s reported arguments is that Yemen’s president has already agreed, albeit in secret, to the killing of Awlaki. It’s bad enough that our own president should be so evasive on this matter, without our citing the unaccountable fiat of another one who seems to have forfeited the confidence of his people.

Future Awlakis should have their day in court, however much we may have to grit our teeth, because the plain text of two constitutional amendments requires it, and because it might whisper to quite a large watching audience that America takes its ideals seriously, and politely expects its fortunate citizens to do the same.