In the 19th century, when national election results were slow to arrive and unevenly distributed, candidates were expected to maintain a certain gentlemanly aloofness from the electoral process. Losers in presidential races tended to concede privately, or, later, through statements printed in newspapers. But as communications improved and media saturation increased, public concession statements, augmented by courteous messages between opponents (often shared with the press), became de rigueur. The visible proof of courtly communication between rivals served to defuse any anger over the result—anger that might manifest more acutely in an era when everyone found out about the outcome at once.

William Jennings Bryan sent William McKinley the first congratulatory telegram two days after the election of 1896. “Senator Jones has just informed me that the returns indicate your election, and I hasten to extend my congratulations,” he wrote. “We have submitted the issue to the American people and their will is law.”

In his memoir of the campaign, Bryan wrote: “This exchange of messages was much commented upon at the time, though why it should be considered extraordinary I do not know. We were not fighting each other, but stood as the representatives of different political ideas, between which the people were to choose.”

After Bryan’s groundbreaking olive branch, the concession telegram became standard practice. Even as telephones became an integral part of daily life, politicians continued to use the wire to extend carefully worded messages of graceful congratulation. Theodore Roosevelt to Woodrow Wilson in 1912: “The American people by a great plurality have conferred upon you the highest honor in their gift. I congratulate you thereon.” Adlai Stevenson to Dwight Eisenhower, in 1952: “That you may be the servant and guardian of peace and make the vale of trouble a door of hope, here’s my earnest prayer.” The only defeated nominee in all that time to skip the telegram was Thomas Dewey, who in 1944 delivered an early-morning public concession statement over the radio. This peeved his opponent Franklin Roosevelt, who extended his own backhanded pleasantry via telegram: “I thank you for your statement, which I have heard over the air a few minutes ago.”

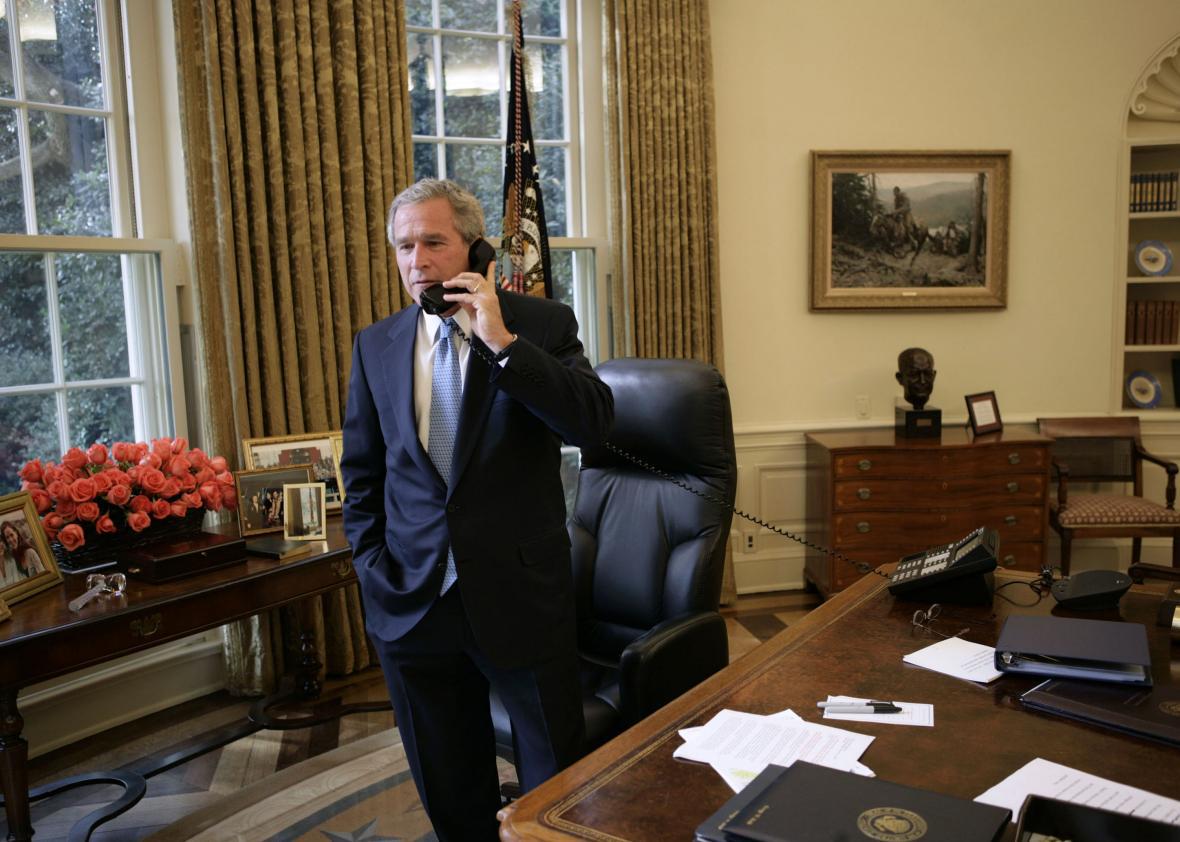

In 1968, Hubert Humphrey called Richard Nixon on the phone as well as wiring him a concession message. By 1980 or so, the use of telegrams had faded away, replaced entirely by the now-familiar phone call. Some losing contenders might like to return to the days of the telegram, which made it easier to present a façade of composed dignity in the face of defeat. Speaking with Mark Leibovich in 2010, George McGovern recalled his feelings on the night he lost to Nixon in 1972. “I didn’t do a phone call, I just sent him a telegram,” McGovern said. “I was somewhat wiped out by the extent of the landslide. So I figured that would be the easier way to do it.”

I relied upon Scott Farris’ Almost President: The Men Who Lost The Race But Changed The Nation in writing this Explainer.