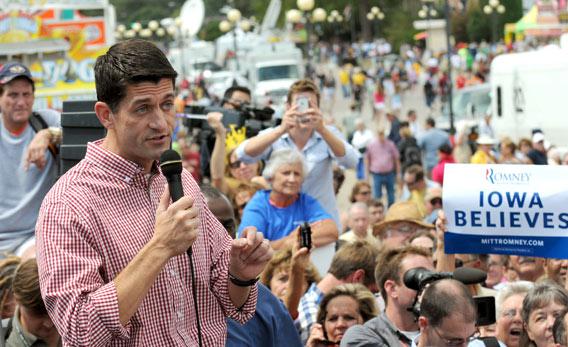

Paul Ryan took to the soapbox at the Iowa State Fair on Monday to make his first solo appearance as Mitt Romney’s running mate. The Republican vice-presidential candidate was soon heckled. Why are speakers said to get up on “soapboxes”?

Socialists popularized the use of the boxes as podiums. Stacks of wooden soapboxes were common in the streets and alleys of American cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where they were piled up to be retrieved and reused for future shipments. Because they were cheap and ubiquitous, they were not well-guarded, and were often borrowed or stolen for personal use—just as milk crates and shopping carts are today. Many of these soapboxes were used for transporting soap—it was in the 1880s that soap for cleaning the body began to catch on with the masses—while others were used to transport other goods, just as milk crates are often used for products other than milk. Borrowed soapboxes weren’t used only for speechifying: By 1903, children were known to commandeer them to make “soap-box wagons” (the predecessors of the soapbox derbies that began in the 1930s), while other enterprising fellows peddled them to parade-goers who wanted a better view.

Some late-19th-century newspapers mention people standing on soapboxes to hand out leaflets, or sitting on soapboxes to tell stories, but it was only at the very beginning of the 20th century that socialists made preaching on soapboxes into a national phenomenon. A 1900 Chicago Tribune article described a pioneering soapboxer who began his campaign with a speech in the street. The subheadline explained, “Mounted on a Soap Box at Commercial Avenue and Ninety-second Street, the Socialist Candidate for Governor Addresses a Small Crowd.” In 1903, the Chicago Daily Tribune described the campaign of the socialist candidate for mayor of Chicago as “rest[ing] on the more or less firm foundation of sixty-two soap boxes” (the candidate had placed socialist orators on soapboxes at 62 crowded corners and streetcar stops). Jack London, who was a socialist himself, described socialist soapboxers in his stories, including in his 1907 memoir The Road (“I get up on a soap-box to trot out the particular economic bees that buzz in my bonnet”) and in his 1908 dystopian novel The Iron Heel (which describes “a man on a soap-box who was addressing a crowd of workingmen”).

Some feared the soapboxers were inciting treason, while others found them a bit preachy and annoying. In 1918, future president Warren G. Harding, then a senator, attacked “soapbox agitation,” and warned that “No Government founded upon soapbox philosophy ever endured.” A harangue against soapboxers in the New York Times around the same time declared that “the heel of authority must crush the heads of the serpents of sedition before they have become too numerous.” Some soapboxers were feared to be immigrant agitators and spies, and many were accused of sedition and sentenced for disorderly conduct. Others fought soapboxing with soapboxing. A 1918 letter to the editor of the New York Times, which noted that “soapboxing threatened to become the city’s most popular sport,” called for young men to “give us a little of the good old rambunctious, star-spanglistic propaganda—the proper kind.” The Socialist Party of America scrapped its soapboxes in 1923, considering them ineffective.

Of course, socialists weren’t the only soapboxers, and many others quickly followed their leads. As early as 1902, the well-to-do preacher of John D. Rockefeller’s congregation surprised the residents of Cleveland when he climbed on a soap box with his Bible. In 1915, several New York City women took to soapboxes to fight for suffrage, and one woman said, “It isn’t hard. You get up on the box and make any kind of a noise and then the people appear.” Even a young George Romney made a name for himself by preaching on soapboxes as a Mormon missionary in London, which might explain his son’s own penchant for standing on things.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks Katherine Ashenburg, author of The Dirt on Clean, and Grant Barrett, co-host of A Way with Words.