This article originally appeared in Inside Higher Ed.

Even if the adjunct movement for better working conditions succeeds, most adjuncts will lose. That’s one bold claim of a recent paper on the costs associated with a number of the movement’s goals, such as better pay and benefits. While activists and scholars have been quick to criticize what they call the paper’s inherently flawed logic, the study’s authors say it is a first step in a more critical dialogue on the adjunct “dilemma.”

“Our goal in this paper is neither to affirm nor to deny that universities owe adjuncts more than they currently receive,” reads “Estimating the Cost of Justice for Adjuncts: A Case Study in University Business Ethics,” published in the Journal of Business Ethics. “Instead, our goal is to show that any attempt to help adjuncts faces unpleasant trade-offs and serious opportunity costs. Due to budget constraints and other factors, many proposed solutions to the adjunct crisis are likely to harm rather than help most current adjuncts. Even if adjuncts deserve much more, it may not be possible to give them what they deserve.”

Authors Jason Brennan, an associate professor at Georgetown’s McDonough School of Business, and Phillip Magness, policy historian and academic program director at the Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University, base their claim on several assertions. They argue that it’s unclear if universities with limited resources wishing to do the “most good” or advance social justice should increase adjunct pay instead of, say, cutting costs or reallocating funds to scholarships. They also note that part-time faculty who are not tenure track “choose to work as adjuncts over their other, possibly quite bad options,” including unemployment, and that universities “do not literally enslave adjuncts.”

Brennan and Magness say, perhaps most central to their main point, that because many colleges and universities face budget constraints and because adjuncts are “significantly less expensive than tenure-track faculty, any attempt to improve the pay and conditions of adjunct faculty will encounter unpleasant trade-offs.”

If, for example, a college stopped hiring adjuncts at what some have called “poverty wages” and instead hired them at higher pay with full benefits, it realistically could only do so for a minority of current instructors—and the rest could lose their jobs, the authors say. “Removing the opportunity to work as an adjunct will harm the typical adjunct, unless that opportunity is replaced with an even better opportunity.”

According to the authors’ rough calculations, institutions across academe currently employ 752,669 adjuncts to teach 1.5 million courses annually, costing about $4.3 billion. Per-course pay in that estimate is $2,700—a commonly cited national average.

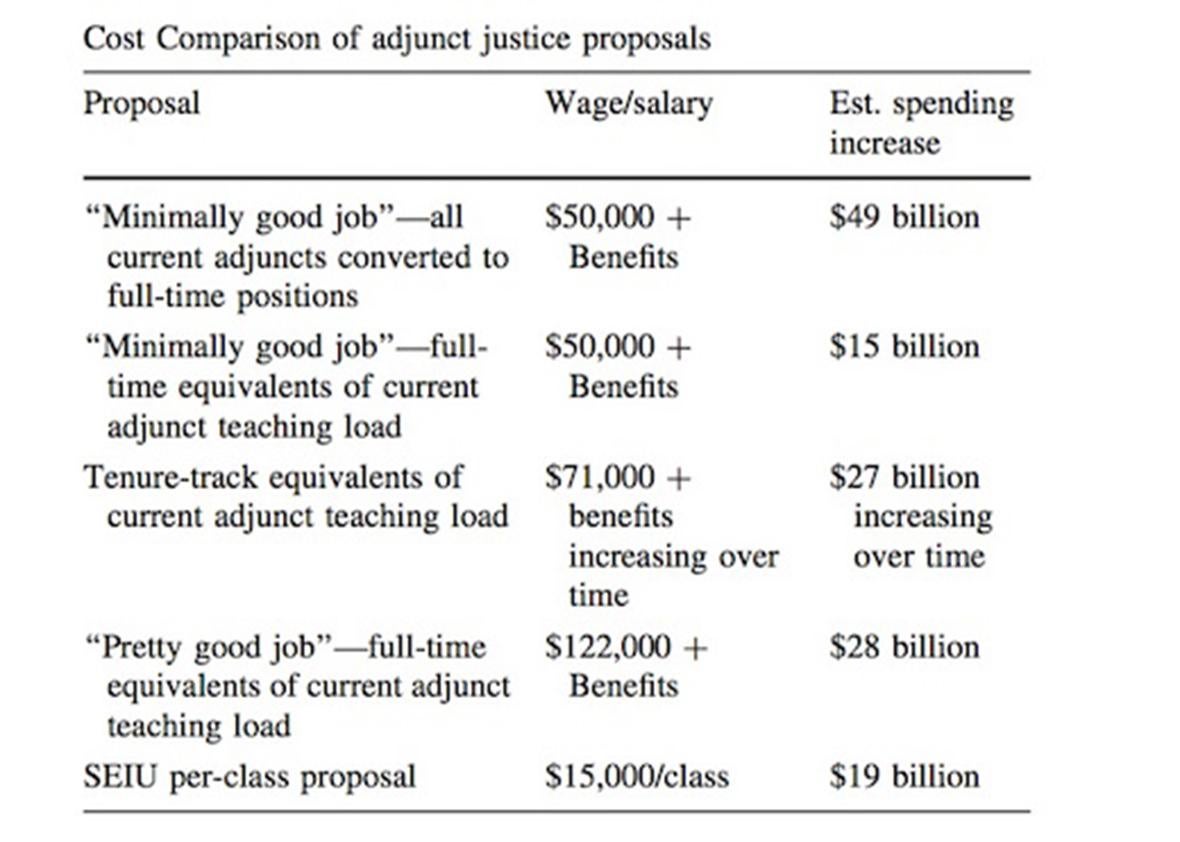

To illustrate their point, Brennan and Magness put together a “minimally good job” package, including a $50,000 salary (teaching six courses per year) plus benefits and office space that would cost a university $72,000 annually. To replace these 752,669 adjuncts with 263,056 minimally good jobs would cost universities $18.9 billion, they say—nearly $15 billion more each year.

If that doesn’t sound like much of an increase, the authors argue, that’s just base costs, without merit raises that could be earned in subsequent years or other perks. To replace those minimally good jobs with something even better—75 percent of the average tenured full professor’s pay of $122,000—the cost would be about $32 billion a year.

The paper references Service Employees International Union’s aspirational proposal that adjuncts be paid $15,000 per course (including benefits), estimating that would cost universities $19 billion more annually.

Journal of Business Ethics

Putting the estimated cost increases into perspective, the authors say it’s “far from obvious” whether universities would be able to afford such a change. According to U.S. Department of Education data from 2013, public and private colleges and universities spent $477 billion on all expenses. About $139 billion went to instruction, with about $100 billion spent on faculty salaries, wages, and benefits.

Making the proposed pay adjustments would mean increasing that figure by 15 to 50 percent—some $15 billion to $50 billion—the authors say.

Perhaps just as importantly, the authors say moving to fewer, better jobs even at a much greater cost would still mean the end of jobs for about 450,000 adjuncts. While the authors take no position on the matter, they say that an “intellectually serious theory of adjunct justice must acknowledge and resolve it.”

Building on that argument, the authors say that increasing pay and benefits and otherwise improving working conditions for faculty would attract “more and better” candidates to such positions, “many of whom will outcompete current adjuncts for their jobs.”

Again referencing the SEIU proposal, the paper says that at four courses each in the spring and fall, “this is $120,000 in pay for nine to 10 months of relatively fun work, with summers and winters off.”

Brennan and Magness argue that any attempt to give adjuncts better jobs is also likely to affect course offerings, “possibly to the detriment of its students. … There would be a drop in the number of faculty and the number of classes offered, and so average class sizes would increase.” There’d be less diversity in terms of classes, and many more tenure-track faculty members would have to teach introductory courses, at the expense of upper-level ones, the paper says. Professionals who moonlight as adjuncts in business and law or other fields also would teach fewer courses, costing students their “real-world experience.”

The authors describe the paper as “taking the first step toward serious work on questions of exploitation in academic employment.” While many claim the obstacles to “adjunct justice” are budget cuts, faculty indifference, and “administrative greed,” they say, the matter is “far more complex and the obstacles more challenging.”

Unsurprisingly, adjunct activists found much to criticize. Joe Fruscione, a former adjunct professor of English and co-founder of PrecariCorps, a nonprofit that offers temporary financial assistance to struggling adjuncts, says Brennan and Magness seem “almost willfully ignorant that many adjuncts are exploited,” with their repeated declarations of having “no stance” on that issue. Over all, he says, their argument seems to imply—falsely—that if “all adjuncts can’t get a raise, none should.”

He says the paper seemed to be “deflecting” some important issues, including by focusing too much on the $15,000 SEIU proposal, which some say is too ambitious. “Yes, that’s high, but this doesn’t mean adjuncts should get paid $2,700 per course on average,” Fruscione says. “There’s a large financial middle ground here, and [they’re] seeing the majority of adjuncts as hobby professors who teach for ‘fun.’ This may have been the majority in the 1970s or 1980s, but it’s not true for the majority now. Most adjuncts don’t have a separate, full-time income stream to make college teaching ‘fun.’ ”

Carol Nieters, executive director of SIEU Local 284, which represents adjuncts at Hamline University in Minnesota, defends the $15,000 per course pay and benefits figure, saying it’s “really about equality, justice, and an indicator of whether a campus is investing in instruction and a stable learning environment.”

Overall, she says, the report “pits students against underpaid adjuncts as a way to avoid the real crisis in higher education, where faculty are marginalized and students are saddled with outrageous amounts of debt. When 1 in 4 families of part-time faculty are enrolled in one or more public assistance programs, we need a dramatic change.”

Fruscione also takes issue with the assertion that adjuncts actively choose to work in higher education over other presumably worse choices. Such an argument would be fine if higher education were truly meritocratic, he says, “but it’s not.” To say adjuncts prefer low-paying jobs “is again problematic, because academia isn’t a level playing field. Whether they see it or not, adjuncts are exploited.”

Responding to criticism that the paper devoted too much attention to SEIU goal, Brennan says in an email interview that it turns out not to be the most expensive proposal considered. That said, he adds, the paper attempts to identify some of the “explicit costs as well as some of the opportunity costs” of adjunct goals. “Any money spent helping improve the plight of adjuncts has to come from somewhere, and is not money being spent to, say, reduce tuition for low-income students or reduce student debt.”

Even if the proposal were simply to increase per-class average pay from $2,700 to, say, $5,000, that’s another $3.6 billion nationwide per year, he says. “That money could be spent helping adjuncts, but it could also be spent doing other valuable things, perhaps things that are more pressing from a social justice–oriented point of view.”

Brennan acknowledges that his institution hasn’t opposed an adjunct faculty union affiliated with SEIU (even though some of its Jesuit peers have objected to such drives on religious grounds), and that Georgetown adjuncts—who already receive relatively high pay—have seen modest pay increases under their contract that haven’t thrown the campus into financial straits or resulted in mass job losses.

He attributes that to the fact that Georgetown has “deep pockets” compared with most institutions but also its values. “The Jesuits have an ideal of cure personalis—care for the whole person,” he says. “That ideal includes principles that require employers to view employees not merely as people with whom they [have an] economic transaction, but as people who deserve respect and extra concern. Rather than interfere with the SEIU, our administration welcomed them.”

Still, Brennan says he hopes the paper highlighted what “no one else seems to notice,” that “realistically, universities can help some adjuncts, but only by firing the rest. Realistically, the adjuncts’ rights movement will benefit a minority of current adjuncts but require the majority to seek employment elsewhere.”

Adrianna Kezar, professor of higher education and director of the Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty and Student Success at the University of Southern California, says the paper nevertheless lacks the impact and “nuance” it’s trying to achieve. The cost calculations are notable to some degree, she says via email, but lack any consideration of university budgets beyond current instructional costs.

In other words, the paper doesn’t examine university budget trends and suggests “costs in other areas could not be decreased to pay for faculty salaries,” Kezar explains. “That is a viable option that is not even considered or addressed. … Assuming many adjuncts have to be fired to pay the remaining more is a flawed examination of the issue[.]”

Another faulty assumption, Kezar says, is that there’s a one-size-fits-all answer of paying all adjuncts equally—something higher education has never done. A better proposal would be for full- or nearly full-time “mainline” instructors to earn more as institutions move back to a “true” adjunct model, under which working professionals who teach a class on the side (about 15-20 percent of the faculty) could have a different pay structure.

Beyond the numbers, the paper is a flawed “set of ideological arguments—mostly trying to persuade readers that even beyond cost there is no logical reasoning to make such a redirection of funds,” Kezar says. For example, she says, having more core faculty members teaching introductory courses is actually a good thing in terms of student success, and her research suggests deans want to see these instructors teaching more lower-level courses and adjuncts teaching more specialized upper-level courses.

The paper’s one “legitimate” argument might be that class sizes would increase to rectify the pay issue, but classes are generally already “very large,” she says.