I arrive in Baltimore with three sources for my preconceptions: Nina Simone (“Oh, Baltimore/Man, it’s hard just to live”); The Wire (count the expletives before the opening credits); and the cult films of John Waters (which boil down to “lock up your children – this place is full of freaks!”).

Nothing on the drive from the city’s Penn Station to Waters’ house fits any of these images. The cab takes a neat, wide avenue past handsome old mansions and a better class of apartment block to a compact, low-slung house on a side street. “We have edge here, but it’s about neighbourhoods. Each neighbourhood is like its own country,” Waters observes as I walk in with the photographers: “It’s almost like you need customs at each boundary.”

He began life 65 years ago in a nearby suburb, Lutherville, and has spent 21 years in this house, perplexing a film industry that does not know how to classify someone not from Los Angeles or New York. The city is getting over its inferiority complex, Waters says, attracting “kids from New York” with its music scene and affordability. “It’s amazing here what you can get for your buck. As they say, we make a dollar holler. That’s a Baltimore expression,” he adds with a dash of civic pride.

Few people embrace preconceptions like Waters, who revels in the clichéd tags attached to him, from “Pope of Trash” to “Prince of Puke”. In 17 low-budget films since 1964, including Pink Flamingos, A Dirty Shame and Female Trouble (“A high point in low taste”), he has courted notoriety by featuring an excrement-eating drag queen, a suddenly sex-crazed suburban mother and a chicken crushed by a copulating couple. Yet the taboos are always broken with a wink, as well as terrible overacting and a lot of dancing. So Hairspray could be turned into a Broadway musical that grossed more than $250m, then be remade as a PG film. Cry-Baby was similarly repackaged, though less successfully, as “a sexy musical for the whole family”.

Waters is an accommodating provocateur, and ushers us into a living room that feels overheated. Bookshelves line the walls but they are not enough. The coffee table, desk and side tables are heaped with books, as is the replica electric chair in the hall. They range from Taschen art tomes such as The Big Butt Book to Jean Genet paperbacks and a Hungarian translation of Tennessee Williams with a pulp fiction cover. In one corner sits a doll from the horror spoof Seed of Chucky, in which Waters appeared. It feels like an eccentric professor’s study, or a carefully curated exhibition based on the life of a fictional character.

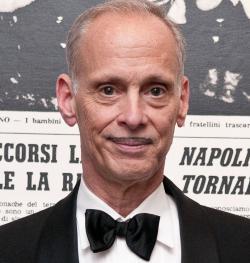

Waters sports a pale striped shirt buttoned to the neck, a linen jacket and a pencil moustache that is much darker than his greying hair. He pulls out an instant camera and motions us into a pose. “I take a Polaroid of every person that’s ever been in my house … from the phone man to the worst night I ever had,” he explains. He takes just one shot. “Nobody can see [it] until I’m dead and they’re [all] dead,” he says cheerfully as he files us away.

I have come to talk about Waters’ one-man Christmas show, which he is bringing to London’s Royal Festival Hall on December 5. Sitting cross-legged on a red couch, one pale blue canvas shoe resting on a coffee table, Waters says “people choke” when they hear he is doing a Christmas show, but insists there is nothing ironic about it. “I’m trying to open up new questions such as, is Santa erotic?” he says, a half-smile on his face, eyebrows arched. I can see the direction his show might head.

I ask what Christmas was like when he was growing up. He recalls his Catholic mother, now 86, taking him to midnight mass, then sidesteps into an anecdote about Glenn Milstead – the boyhood friend and cross-dressing muse he named Divine – coming to the service in drag. Waters’ stage shows are carefully scripted, delivered from memory, and these rapid digressions come across like a compressed rehearsal of one of his soliloquies.

“I liked Santa but I would get confused as a child whether I was supposed to pray to him or William Castle [the B-movie director], or Jesus,” he says, before skipping to another thought about “living crèches” – Christmas cribs re-created with real people. “They’re begging for Diane Arbus to come back from the grave to take a picture of them. What parent would give their child to be baby Jesus, with straw and candles and mules that kick … ? I’m telling you, I think living crèches are some of the most horrifying things.”

Waters has been doing stage shows since the 1960s, when he appeared at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco and toured campuses to promote his films. “We were starting out in colleges, which was the only market, really, for midnight movies. I came on stage dressed like a hippie pimp. Divine would come out, rip a phone book in half, and throw dead mackerel at the audience.” If they had the money, the pair would hire an extra to wear a police uniform and pretend to arrest them: “Divine would strangle him to death – and the movie would start.”

Thinking of Christmas in London, I ask whether Waters has seen any pantomimes. He looks puzzled. I try to explain the genre that combines fairy tales, audience participation and washed-up TV stars in women’s clothing. “Is there scat in it?” he asks.

Mores have moved on and audiences are harder to shock, and I ask what counts as transgressive today. “Transgressive is not trying too hard,” he replies. “There are always new things that startle me.” In Spain, he says, he heard about “balloonies”, or people with a sexual interest in balloons. “I really don’t get it. But maybe I’m being stuffy. It’s safe. We should encourage that kind of behaviour. No one gets pregnant at a balloony party.”

He has swiveled again from the salacious to the jokey, and it occurs to me that this is what Waters does: confront the audience with something transgressive and render it unthreatening and comical. He relishes words like “creepy”, “hideous” and “filthy”, but makes them sound like good, clean fun. “I think when people come to see my movies or read my books or come to my Christmas show, they want me to take them somewhere they wouldn’t go. And with me as their guide, they never get mad, because I’m not saying you should do this. I’m saying, isn’t it amazing, human behaviour?”

With his books never out of print, his films on Netflix, children going to the Broadway versions and Waters narrating the part of Jessica the Hippo for Animal Planet, I ask how he likes life in the mainstream. “It’s great. It’s the final irony in my life,” he answers. “I think we need a new vocabulary, because [now] everybody wants to be an outsider. When I was one, no one wanted to be one.”

He has mixed feelings about gay culture becoming mainstream: “I miss it … I’m for gay marriage. I don’t want to do it, but I certainly think people should be allowed to, and I wouldn’t vote for anybody that would be against it. But at the same time, why do we have to be good now? Why can’t we be villains in movies?” He says it’s good that more people are able to come out of the closet, but adds: “I wish some gay people would go back in. We have enough.”

The subjects he explores in his films, including homosexuality, racism and rebellious youth, have not always been recipes for uncomplicated happiness, but Waters describes himself as “a happy neurotic”. He adds, though, that he will never retire, because “then I’d have time to be nuts”.

He took a one-man show, This Filthy World, to Australia and New Zealand in October, and in recent months he has served as guest curator at the Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis, worked on a book, exhibited in New Orleans, taken part in events from the Bonnaroo music festival in Tennessee to the Venice Biennale, and provided a Vincent Price-like cameo for the video of “The Creep”, a comedy hip hop song featuring Nicki Minaj. Still, he says (a little defensively): “Friday night I went out, wildly had a party until five in the morning with a bunch of friends, so it’s not like I’m a workaholic.”

“I have a lot of plan B, C, D, E, and F in effect,” he adds. What’s plan A, I ask? “Plan A is to make movies. The one thing I can’t do right now.”

He finds himself in a cinematic no-man’s land. Hollywood studios look only for blockbusters, while the demise of art-house cinemas makes investors reluctant to finance independent films. The last half-dozen films he made cost between $4m and $8m, he says. “Nowadays, [backers] want it to cost $500,000 to $1m. I can’t do that because I have four employees. I can’t work for nothing for two years. I’ve done that. I can’t be faux underground.”

A planned Christmas film, Fruitcake, was shelved in 2009 when the production company folded. Waters still hopes to make the film. The plot – boy runs away when he’s caught shoplifting, meets runaway girl raised by gay men who’s searching for her birth mother – “would be incredibly commercial”, he says, straight-faced.

US censors gave A Dirty Shame, Waters’ last film, an NC-17 rating in 2004, classing it with adult films and severely limiting its commercial prospects. Waters is still fuming: “Dumbbell censors are easy. You use their quotes in the ad. Liberal censors are much harder to fight,” he says.

Television now offers more creative freedom than film, Waters argues. “There’s certainly worse taste on television than I ever did. People have seen everything today … At the same time, I think young people are still having fun. I never think my time was better. I think they’re having the same amount of fun because it’s something new to them. They’re down at the Stop the Wall Street thing, which is, to me, hilarious.”

Long before Occupy Wall Street, Waters was fond of protesting. “Riots are fun. I hate to say that, but in the Sixties I went to all of them. I was a Yippie. I was a Weathermen hag.” One of his youthful protests was a “Burn the Bank of America” rally, but now he banks with his former target. “I recognise the irony of it,” he admits.

He now believes in capitalism, he says, “because the more success I have, the more people I have to hire,” and he is embarrassed to think that he marched against the construction of the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco (“Now when I look at it, it’s the most gorgeous architecture”). Will the counterculture win, I ask? “Counterculture won some things a long time ago. Counterculture’s in control. I’m the insider. I’m the establishment. I’m not struggling,” he replies.

For Waters, culture has always been tied up with music, and I ask what he is listening to these days. He puts on a pair of black-framed glasses and goes to his desk, handing me CDs from one of several large stacks: Beach House, a Baltimore indie band; Die Antwoord, a self-described “futuristic rap-rave crew” from South Africa; and Duffy, the soulful Welsh singer-songwriter. Waters himself has released an eclectic compilation of Christmas songs as well as a Valentine’s collection called A Date with John Waters, but says another album looks unlikely as there are few record stores left in which to promote it. He still prefers to go to record shops and cinemas rather than streaming music and films at home. “I’m an old person,” he shrugs.

If he were starting out now, would he make YouTube videos? “No, because I don’t want to run an ad agency,” he replies. The video for “The Creep”, seen more than 45 million times, “was good for my street cred” but made him little money, “and if you make something on YouTube that becomes a huge hit, you get offered a job at an advertising agency, not to be a film director.”

Television, however, appeals to the man who describes The Wire as the best thing on TV since Pee-wee’s Playhouse (which ran on CBS from 1986 to 1990). A TV Christmas special remains an ambition for Waters: “It would be funny, but it would pay tribute to [the genre] and do it in a new way, like Lil Wayne singing ‘Little Town of Bethlehem’,” he muses. “I could make it au courant, and at the same way, respect the traditions.”

It is time for the photographers to do their work, but Waters has not finished his show. “I just got some art through,” he says, gleefully handing me a limited edition glass ashtray with the words “Walden Pond” at the bottom. Next comes a crucifix-shaped lighter, then he takes us upstairs to see a new acquisition. He points down, near the skirting board, and I see that what I thought was an electrical socket is a miniature trompe l’oeil painting by Douglas Padgett. Back downstairs, as he poses in front of a faux-marble bust he “found in the trash”, he draws my attention to a collection of pewter architectural models called Buildings of Disaster, including the tunnel where Princess Diana crashed, the motel where Martin Luther King was shot and the Twin Towers.

As we prepare to leave, Waters says the Polaroid that he took of us will be archived with his films when he dies, in the same place as the works of Ingmar Bergman, Martin Scorsese and Clint Eastwood. It sounds a little like the communists who arranged to be buried near Karl Marx in Highgate cemetery, I remark. “Oh, I’ve already bought my grave plot. It’s in the same graveyard as Divine. We all bought them there. Mink [Stole, the actress who appears in all his feature films], Dennis Dermody [the film critic], Pat Moran [his best friend in casting]. It’s like Disgraceland.”

Will it be a lavish headstone? “No. I like Pasolini’s; he had just his name and the date. He’s my mentor in gravestones,” Waters laughs. Tasteful, then? “Yes, I think gravestones should be quite simple.” Some jokes, he adds, just don’t age well.

This article originally appeared in Financial Times. Click here to read more coverage from the Weekend FT.