On July 22, 1851, on a day when a visitor to London had any number of amusements at his disposal—from M. Gompertz’s Giant Panorama (“including a new diorama of intense interest”) at the Parthenium Rooms on St. Martin’s Lane, to the “Real Darkies from the South” (replete with “the Sayings and Doings and Lights and Shadows of the Ethiopian race”) appearing at Gothic Hall—a group of men assembled in a small room in Westminster.

They were drawn by a curious invitation: “To witness an attempt to open a lock throwing three bolts, and having six tumblers, affixed to the iron door of a strong room.” The men gathered around the door to a vault, once the repository of records for the South-Eastern Railway. At their center was an unassuming figure, an American named Alfred C. Hobbs, clad in waistcoat and collar. At 11:35 a.m., Hobbs produced a few small tools from his pocket—“a description of which, for obvious reasons, we fear to give” a correspondent for the Times wrote—and turned his attention to the vault’s lock. His heavy brows knitted, Hobbs’ hands flitted about the lock with a faint metallic scratching. Twenty-five minutes later, it opened with a sharp click. Amid the excited murmur, the witnesses asked Hobbs to repeat the task. Having relocked the vault, he once again set upon it with deft economy. The vault opened “in the short space of seven minutes,” as the witnesses would testify, “without the slightest injury to the lock or the door.”

The lock was known as the “Detector,” and it needed no introduction. Indeed, since its patenting in 1818 by Jeremiah Chubb, a Portsmouth ironmonger, it had become one of the country’s most popular locks, advertised in the Bleak House serials and enshrined in magazine doggerel: “My name is Chubb, that makes the Patent Locks; Look on my works, ye burglars, and despair.” It was renowned for its impregnability, having survived any number of picking attempts; in one trial, a notorious London picklock, given a chance at a pardon if he could crack Chubb’s masterwork, testified “that these locks were the most secure he had ever met with, and that he did not think it possible for any man to pick or open them with any false instruments whatever.” But it was also famed for its “Detector,” an anti-picking lever that tripped the bolt if any of the lock’s six standard levers were lifted too high. “In this state the lock is what I call detected,” wrote Chubb in his patent, “and the possessor of the true key has evidence that an attempt has been made to violate the lock, because the true key will not now open it.” (If the lock had been violated, its owner could retrieve his belongings by using a “regulating key” that would not open the lock but rather restore it to its original, openable condition.)

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Given the failure of all previous picking attempts, the arrival on July 21 of a letter, headed “American Department, Crystal Palace,” at the firm’s offices likely brooked small concern. “An attempt will be made to open a lock of your manufacture on the door of a Strong-room at 34, Great George Street, Westminster, tomorrow, Tuesday, at 11 o’clock A.M. You are respectfully invited to be present, to witness the operation.” Chubb, perhaps mildly piqued, sent a man to watch. But the letter was a gauntlet, and it had been thrown. Hobbs had not only opened the lock, but he had opened it again. The Detector had been foiled.

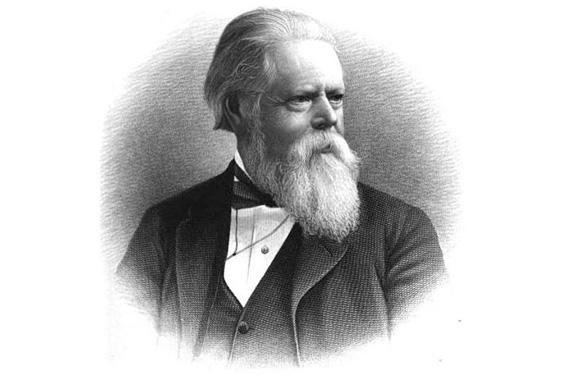

Hobbs had a penchant for this sort of thing. Born in 1812 to a Boston carpenter—whose death not long after left the family destitute—Hobbs rambled through a number of professions in his teens: farmhand, dry-goods clerk, carriage painter, coach trimmer, harness maker, firefighter, sailor, glass cutter, and, eventually, exclusive vendor of safe locks for the prominent New York City firm Day and Newell.

Hobbs quickly determined that the best way to sell someone a new lock was to expose the weakness of their current one. And so, for several years, Hobbs toured America, calling upon banks, “equipped with a lock and suspicious implements.” In 1848, Hobbs responded to an ad, placed by a “Mr. Woodbridge, of Perth Amboy” wagering $500 that a safe in the Merchant’s Exchange reading room could not be opened. As one account notes, Woodbridge had rigged the lock so the bolt would catch if tried before the tumblers were set, rendering it unopenable. Hobbs worked on the lock for a few hours in the evening, before retiring for the night. In the morning, as a crowd gathered, Hobbs requested Woodbridge. “Hallo, Mr. Hobbs, what is the trouble?” Woodbridge replied. “There is something the matter with the lock,” Hobbs said. “What is it?” asked Woodbridge. Hobbs, opening the safe, said, “Your lock won’t keep the door shut.”

And so, like some kind of midcentury Melvillean trickster, Hobbs roamed the country, a succession of sprung doors and flabbergasted bank managers in his wake. In April 1851, Hobbs boarded the steamship Washington, bound for Southampton, for a task of a different nature. He was bound for London’s Great Exhibition, where Day and Newell’s “Parautopic Lock” (from the Greek, for “hidden”) would join the teeming cavalcade of objects—numbering more than 100,000—on display.

Officially, Hobbs was a salesman en route to a trade show, traveling across the Atlantic to help Day and Newell promote their new lock. But the American had additional plans. Among Hobbs’ luggage was a small trunk with six drawers’ worth of lock-picking tools; and, to help smooth the passage through customs with a bevy of illicit implements, a letter from George W. Matsell, New York City’s chief of police, which announced: “I can unhesitatingly bear ample testimony to your character as a gentleman and a citizen.” What Hobbs had in mind was not the usual cajoling of a provincial bank into an upgrade, but exposing weaknesses in the British Empire itself by revealing the faults of one of Day and Newell’s competitors.

In the window of Bramah and Co., Engineers and Founders, at 124 Piccadilly, sat a lock and a small printed board, which announced: “The Artist who can make an Instrument that will pick or Open this Lock, shall Receive 200 Guineas The Moment it is produced.” The Bramah Precision lock, a “monster” lock that, along with Chubb’s Detector, represented the pinnacle of Britain’s lock supremacy, had not been picked since it was manufactured—in 1790.

Not surprisingly, Hobbs had it in his sights. In June he visited the shop to make wax impressions of the keyhole. A few days later, he wrote to Bramah, saying he “would be pleased to see you in relation to the offer you make on the sign in your window for picking your lock.” On July 22, Hobbs and Bramah chose arbitrators and settled on terms: The American would have a month to attempt to pick the lock, which would be mounted in a board in a room above Bramah’s shop. On July 24, Hobbs set to work, armed with various tools, including what the Observer described as a “something like a crochet needle.” On Aug. 23, after logging some 50 hours of work, Hobbs opened the lock. On Aug. 29, upon Bramah’s request, Hobbs opened it again.

It was a click that became a thundershot. “We believed before the Exhibition opened that we had the best locks in the world,” wrote the Times, “and among us Bramah and Chubb were reckoned quite as impregnable as Gibraltar.” But a “Great Lock Controversy,” as the papers called it, was afoot: Had Hobbs opened it properly? Was some form of mischief present? Was the lock safe against normal theft? With the kind of scrutiny normally reserved for contested elections, the press pored over the trial’s details. Bramah protested that while it had granted Hobbs the right to find the single instrument that would open the lock, “we never for a moment agreed that he was to be allowed to keep the spring fixed down as long as he pleased during his thirty days’ labour, and affix his apparatus to the woodwork in which the lock was enclosed, while he used at pleasure three other separate and distinct instruments to assist him in his operations.” Chubb, still stung after what it called the “doings at the empty house in Great George-street,” sniffed with enthusiastic scorn: “We congratulate Mr. Hobbs on the envied honour of having picked a Bramah’s lock after ‘16 days’ labour.’ ” With cool condescension, the Bankers’ Magazine wrote that “the result of the experiment has simply shown that, under a combination of the most favourable circumstances, and such as practically could never exist, Mr. Hobbs has opened the lock.”

Photo courtesy of Samuel Orcutt/Wikimedia Commons

But no matter. The committee awarded the 200 gold guineas (roughly equivalent to $20,000 today), Hobbs became a folk hero (and lock-picking a popular sensation), and Britain’s vaunted image of lock-making supremacy, as inviolable as the locks themselves, was called into question. The Bank of England itself promptly swapped out Chubb’s locks for those of Day and Newell. As to why something as seemingly arcane as locks became a cause célèbre, with the public devouring obscure details of their innermost workings—tumblers, sliders, false notches—the most immediate answer is that Hobbs’ successful challenges occurred during the Great Exhibition, that presumptive showcase of the might and ingenuity of the world’s leading industrial power, and on its home court. It was, in rough contemporary analogy, the Washington Generals defeating the Harlem Globetrotters. But there was more to the defeats of Chubb and Bramah. As historian Jeffrey Auerbach writes, “the Great Exhibition revealed, for the astute observer, signs of underlying weaknesses, the beginning of the erosion of Britain’s economic preeminence upon which its military and imperial strength rested.”

There was another form of insecurity in the air. 1851 was, as it happens, the first year in Britain that cities’ populations outnumbered that of the countryside. In London, the world’s largest city, an emerging middle class with property to guard grew anxious (“we increase in poverty and crime as we increase in wealth,” wrote Henry Mayhew in London Labour and the London Poor, published that same year). The Exhibition itself, England’s first taste of mass tourism, inflamed these fears, as Londoners steeled for an influx of foreigners; the Express urged careful vigilance, “to trace, if possible, under his jaunty, careless manner, the sinister aspect of the spy and the conspirator.” Urban crowding, combined with a rising middle class with new possessions and new wants, created, as historian David L. Smith describes in his fascinating dissertation “Under Lock and Key: Securing Privacy and Property in Victorian Fiction and Culture,” a rising interest in security. “The Victorians,” Smith writes, “were obsessed with security, and patent locks and keys provided them with a set of material signifiers for fundamental middle-class values of privacy, property ownership, domestic propriety, and autonomy.” One German journalist visiting London described a “mania for fortification.” (The rise in perceived, or actual, insecurity was accompanied by a proliferation of lock patents. As Smith notes, “from the beginning of the 19th century until 1851, the government issued some 70 patents for locks. By 1865 that number had exceeded 120; and within the next 55 years it climbed to over 3,000.”)

Hobbs had done more than pick a few locks; he had picked the nation’s psyche. “[I]n this faith we had quietly established ourselves for years,” wrote the Times, referring to the country’s interrelated sense of technological superiority and safety, “and it seems cruel at this time of day, when men have been taught to look at their bunches of keys and at their drawers and safes with something like confidence, to scatter that feeling to the winds.”

The Lock Controversy raised a number of questions about the nature of security and how best to achieve it, and troubled Victorian England with a question that still haunts us today: How safe could something—or someone—ever be?