Listen to Tuesday’s episode of Trumpcast with Bill McKibben:

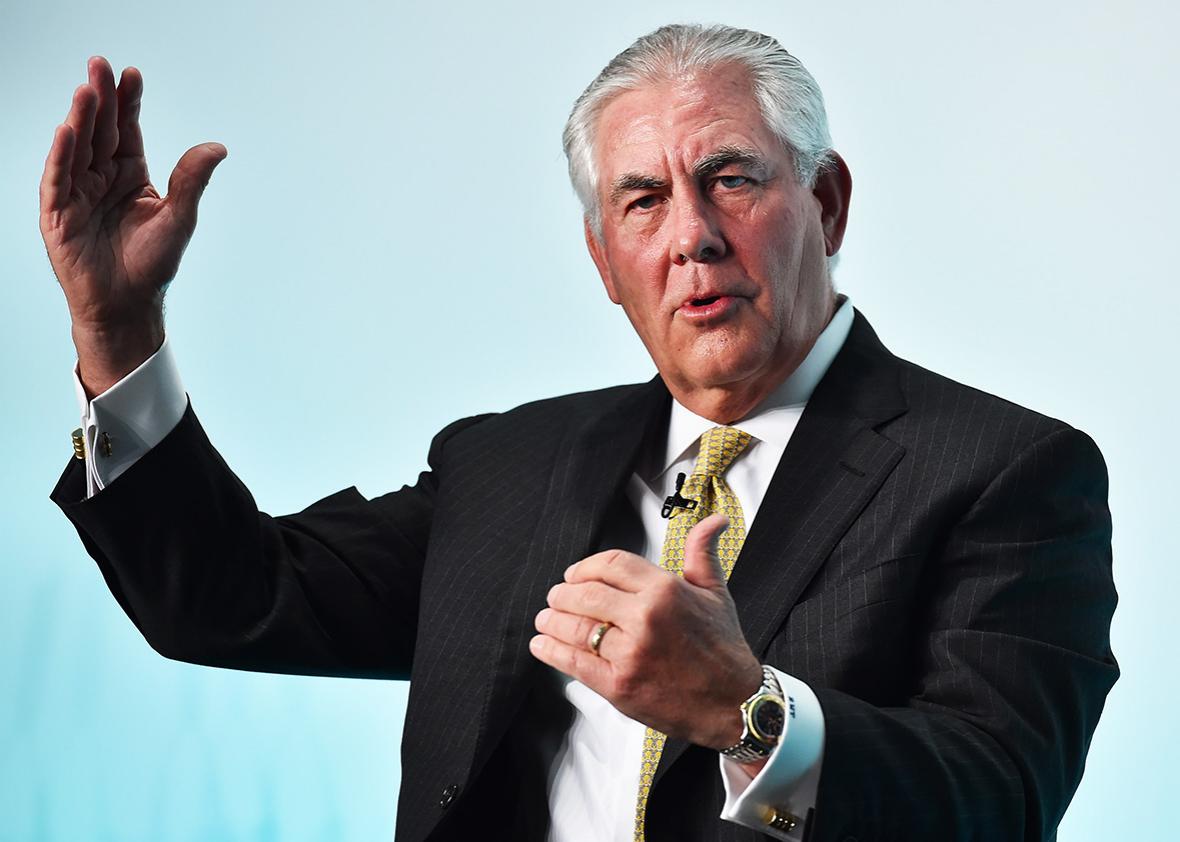

On Monday night, President-elect Donald Trump named Exxon Mobil CEO Rex Tillerson as his secretary of state pick. On Monday morning, Jacob Weisberg invited Bill McKibben—climate activist, author, and founder of 350.org—onto Trumpcast to discuss what Tillerson could mean for the country and for climate change. This interview (which took place before the appointment was confirmed) has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jacob Weisberg: Why can’t the CEO of Exxon be the secretary of state?

Bill McKibben: What’s happening right now is completely fascinating. We’re dropping any pretense. We’re just flat-out saying, Yep, look, we’re run by the fossil fuel industry. Now, the fossil fuel industry has been the most powerful political player in America for many years. The Koch brothers, our biggest oil and gas barons, are the biggest political donors. The GOP is more or less a wholly owned subsidiary of the fossil fuel industry. The Democrats have always been terrified of the fossil fuel industry. But they’ve always operated slightly in the shadows. Now we’re going to turn over the most important post in the cabinet to a man who spent his entire working life at the biggest fossil fuel company on Earth.

Exxon Mobil is the biggest, but is there anything about it in particular? Presumably, you’d have a similar objection to the head of any fossil fuel company becoming secretary of state.

Exxon is remarkable. This is a remarkable reward for what we’ve learned about Exxon in the last year. Great, investigative journalism at the Los Angeles Times, at the Columbia Journalism School, at Inside Climate News—the Pulitzer Prize–winning website—in the last year have detailed the fact that Exxon knew everything there was to know about climate change 30, 35 years ago, and instead of telling the rest of us, they helped mount the massive and effective campaign to make sure that nothing happened about climate. The notion that scientists were wrong, or at least confused, would muddy the waters.

And they’ve muddied the waters so effectively that Mr. Trump went on TV to say, and I quote, “No one knows if climate change is real or not.” Well, everyone who knows anything about the issue knows—every climatologist is very well-aware that by putting carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, we are raising the Earth’s temperature. 2016 was the hottest year we’ve ever measured on this planet. We’re at an absolute hinge moment, not just for our country; we’re at a hinge moment for our geological era. And into that comes Donald Trump and Exxon. If they’re allowed to proceed as they want to proceed, it’s the coup de grâce.

Does Rex Tillerson—and do Exxon Mobil—deny climate change? I was under the impression they’d given a lot of ground there.

They denied it for many, many years.

But do they deny it now?

His predecessor as CEO, Lee Raymond, infamously gave a talk in China during the time when the Kyoto Treaty was being negotiated, telling the Chinese that it was all a bunch of bunk and that they should go ahead and rapidly develop all the fossil fuels they could and it wouldn’t make any difference. The Exxon under Tillerson has been mildly more PR-minded, and so they’ll occasionally put out a statement saying We take seriously the issue of climate change. But whenever Tillerson talks about it, he immediately takes it back. As he said memorably in his most extended discussion of it, “If it’s a problem at all, it’s an engineering problem to which we will adapt.”

As he put it, “If we have to move our crop production areas because of the changes in the weather, we’ll adapt to that.” Well, crop production areas are what I believe normal people call farms. We can’t just move them because we made it too hot to grow corn in Iowa or Illinois. If we do that, where are we planning to move them? Up into Siberia where there’s no soil? These guys are playing games with the most powerful forces on the Earth, and they’re doing it so that they can extend their business model another five, 10, 15 years, at a point where it’s no longer necessary—at a point where renewable energy is becoming as cheap as we could ever want.

Bill, you’ve been involved in this effort to investigate what Exxon has done to cover up climate change, and you follow the company very closely. Tell us a little bit more about Tillerson himself and where he fits in.

His specialty has been making deals with some foreign countries, most notably with Russia. The Wall Street Journal reported that the only American that Putin may have spent more time with than Tillerson is Henry Kissinger, so there you go. Tillerson is such a favorite of Putin’s, having invested huge amounts of money in Russia, that he was literally awarded and happily accepted an Order of Friendship with Russia. He has clearly no personal or corporate problems with Russia’s human rights record, with all of its other activities around the world. He sees it purely as a business relationship, which I guess is now what we will see it as—as a nation.

Exxon Mobil, in a lot of ways, is more like a country than a company. We sort of think of it as an American company—or a lot of Americans do because that’s its history.

They don’t think of it that way.

Yeah, that’s what I was going to ask you. When they deal with Russia, do they think of themselves as an American company dealing with a potential enemy?

Quite explicitly, they’ve said they don’t. Steve Coll, the tremendous reporter, wrote the definitive book on this, a book called Private Empire that came out a few years ago that I reviewed for the New York Review of Books.* Right now, everyone should be pulling it off the library shelf and reading it. It makes it clear: They’ve said very explicitly, We’re not an American company. They’ve gone heavily against American foreign policy time and again—for instance, talking down the U.S. government’s efforts to deal with, say, the Kyoto accords.

In this case, this junction is enormous. If the U.S. government would just lift its sanctions on Russia, imposed after its misadventures in Crimea and Ukraine, then Exxon stands to make billions of dollars—many, many billions of dollars—from its operations in Russia, which it can’t at the moment because of those sanctions. So if you wanted a good potential answer as to why Russia might want to mess around in our political life, well, as our investigative reporters have said over the years, follow the money.

Right. So Tillerson’s interest is basically giving Russia anything they want in terms of Crimea, Ukraine, Syria, human rights, any other issues—get the sanctions lifted. I mean, that’s his interest right now, as head of Exxon.

That would appear to be—and in the larger sense, to make sure that the world is not taking undue or, in his view, rushed or serious action about climate change. Remember, the secretary of state is the guy in charge of negotiating our climate agreements with the rest of the world. His boss, Mr. Trump, has said in the past that he wants to repudiate the Paris climate agreement signed by 192 heads of state.

I’ve seen references to Tillerson himself endorsing the Paris climate treaty and supporting a carbon tax.

Exxon sent out a tweet at some point saying We support the Paris climate treaty. That’s about it. And they’ve said in the past that they support some form of carbon pricing. But no serious thinker believes that they mean a word of it, especially because they’ve continued to dump all their very large political contributions straight into the laps of politicians who’ve made it clear they oppose anything to do with carbon pricing or anything else. We’re clearly not going to get any of that out of a Trump administration.

Put this in the context of a little bit of the things that Trump has already done on climate: What’s the larger picture here?

In all of the various assaults on fact and reason that Trump people have launched, the most central and the most powerful is the attack on physics—the attack on the idea that we’re going to do anything at all about the greatest problem we’ve ever wandered into.

What’s the alternative to despair here? What’s even the point of fighting Rex Tillerson? If you don’t get him, Trump’s just going to appoint someone else who’s probably just as bad on climate change.

I think that that’s a reasonable question. I think that the answer to it, to the degree that there is an answer, is the more resistance we mount, the better the odds that we’ll be able to slow down some of what they’re trying to do. Not all of it: There are going to be a lot of losses over the next six or eight months, no question about that. He’s got power at every branch of government; he’s going to use it. The people around him are ruthless and determined. But after that cascade of losses that are headed our way, the reaction will begin to set in, and I imagine it will set in rather quickly, because I think the damage done to the economy, the damage done to the environment, the damage done to human rights will begin to sit badly with lots of people. That’s the point at which we’re going to have needed all the resistance and all the organization that we can muster, so that we can try and fight back. Not just to reclaim lost ground, but to go deeply in the direction we need to go.

The one thing that I guess should be said is: There’s a certain clarity about this moment that we haven’t had before. The Obama administration helped as America became the largest oil-producing nation on Earth. It’s not like they were not friends to the fossil fuel industry. But their record was mixed; they did a few good things too. So it was harder to have some of these essential, central fights. Now, all pretense is gone. It’s entirely clear what and who is in the driver’s seat, and they own this now. They own the consequences. Hopefully—and this may, at a certain point, be just whistling past the desert—at a certain point, that’s going to have to translate into real and big shifts.

*Correction, Dec. 13, 2016: Due to a production error, an earlier version of this transcript misspelled Steve Coll’s last name. (Return.)