Facilitated communication claims to give a voice to noncommunicative disabled people. A facilitator physically supports a disabled person to assist him in communicating through a keyboard or other device. FC has been repeatedly documented to produce the ideomotor effect, or “ouija board” effect, in which a person unconsciously influences his or her own motor behavior, in this case guiding a disabled person’s hand as a consequence. The literature showing the ideomotor effect in FC is voluminous. In these cases, the facilitator speaks “through” the FC user, believing or pretending that the disabled person is communicating, while in fact presenting the facilitator’s own words.

In October, Rutgers-Newark philosophy professor Anna Stubblefield was convicted of sexually assaulting “D.J.,” a nonverbal 33-year-old man with cerebral palsy, as Daniel Engber recounts in the New York Times Magazine. Stubblefield met D.J. in 2008 and began using FC, holding D.J.’s hand or arm as he typed on a computer keyboard. He quickly displayed remarkable verbal fluency, and Stubblefield brought D.J. to conferences where she facilitated his talk on disability issues. In 2011, D.J. published an essay in Disability Studies Quarterly, “The Role of Communication in Thought,” written via Stubblefield’s facilitation. Around the same time, Stubblefield and D.J. had sexual relations—the acts for which a jury convicted her of two counts of first degree aggravated sexual assault, for which she is currently facing 10 to 40 years in prison. Stubblefield, it turns out, may not have been facilitating D.J.’s speech—only her own unconscious speech.

At the climactic moment of Engber’s piece is a horrific encounter when D.J.’s brother, who had introduced Stubblefield to D.J. after taking a class with her, confronts Stubblefield and asks her to facilitate answers to some questions. D.J. fails to recognize the nickname of his old caretaker, a fact he should easily know, suggesting that Stubblefield and not D.J. was generating the messages. Some disability advocates have stressed that we don’t know what D.J. really felt and whether he consented to sex with Stubblefield or not. But that isn’t really the issue here. The issue is that Stubblefield didn’t know either, and that was enough to constitute criminal behavior.

Stubblefield’s is not an isolated case. Last year, an Australian residential care officer pleaded guilty to two indecent acts on an acutely autistic and apparently noncommunicative 21-year-old, claiming she’d spoken with him through FC. Last year, pharmaceutical executive Gigi Jordan was found guilty of first-degree manslaughter for killing her autistic 8-year-old son with a drug overdose after “he” typed on her Blackberry, via FC, “I need a lot of drugs to die peacefully … I wish u do it soon.”

FC continues in spite of these scandals. Given the long history of sexual abuse allegations and other horror stories, Stubblefield should have known that the ideomotor effect might have been at work. Understanding why she didn’t is a complicated question. Stubblefield was not a single reckless actor who fell prey to romantic irrationality. She was embedded in a pseudoscientific community that has consistently suppressed doubt and boosted the unreliable methodology of FC. Stubblefield did not think she was sexually assaulting D.J. She thought, rather, that she was giving D.J. a voice. This is the core faith of FC, and its central deception and motivation. The community of believers in facilitated communication claim to be letting the disabled speak, when they are actually stealing whatever voices they have.

The “science” of FC not only continues to do damage but is actually gaining ground. It is being used in public schools throughout the country through the infiltration of FC advocates into public positions. FC preys on the hopes of parents and family while taking patients away from reliable and proven treatments that FC proponents deem inferior. Stubblefield may be headed to jail for 10 to 40 years, but those who created her belief system are not only going unpunished but are doing further harm.

In our public education system, FC is making disturbing inroads through the seemingly well-meaning Schoolwide Integrated Framework for Transformation, a $24.5 million disability inclusion program that is the Department of Education’s largest special education grant ever. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan announced the grant in 2012, which allocates money to public schools and nonprofits that support and adopt the SWIFT program. SWIFT is run in significant part by facilitated communication supporters based at the University of New Hampshire and the University of Kansas. Proponents currently play down the term “facilitated communication” in favor of less loaded descriptions like “supported typing,” but the method has not changed. It poses dangers to schoolchildren, schools, parents, and taxpayers.

The method has been repeatedly rejected by researchers and dozens of medical organizations, but it lives on by appealing to the desperate hopes of those who want their loved ones to communicate. Though many thought it wholly debunked in the 1990s, some in the autism community in particular have helped keep it alive as an especially potent form of pseudoscience. FC has been connected with everything from false sexual abuse allegations to telepathic messages to autistic reincarnations of biblical figures. Yet FC retains more credibility within certain academic departments than almost any other cultish fad. In the words of former FC facilitator Janyce Boynton, whose fake communications in a 1992 assault case got a child’s parents falsely charged with sexual assault: “FC is not a communication technique. It is a belief system—and a powerful one at that.” My interviews and research with many FC advocates proved this true time and time again; even when they expressed doubts about the process, all of them, to a one, were heavily invested in the reliability of FC—even as some openly conceded that FC was not reliable. Hope, unfortunately, can be a very dangerous thing.

Axel

FC advocates are on the defensive after Stubblefield’s conviction; many I talked to faulted her for doing damage to their cause. The University of New Hampshire’s Mary Schuh blamed Stubblefield’s “poor practice.” Douglas Biklen, who brought FC to the United States and remains its leading luminary, made one public comment about the case prior to speaking to me, bemoaning not the damage to D.J. or Stubblefield, but to FC: “It is so painful to see facilitation put on trial in such incredibly prejudiced ways.”

The FC opponents I spoke to, on the other hand, expressed sympathy for all involved. “This is not a happy conclusion,” said Eastern Michigan psychology professor James Todd, a longtime critic of FC who testified in the Stubblefield trial. “This reflects a monumental series of errors on a lot of people’s parts and our society’s attempts to try in a very inefficient and rough way to try to solve it.” Harvard Medical School’s Howard Shane, who helped devise the testing to debunk false FC communications as well as creating the legitimate speech system used most notably by Stephen Hawking, blamed not Stubblefield but FC promoters: “Stubblefield is a victim who got sucked into the same cult that her mother was a part of.” Todd was even more blunt: “Biklen has been center of considerable harm and misfortune to thousands of people. Had he exercised proper diligence … he would have tested carefully to see if it worked, seen that it didn’t, and moved on.”

The systematic downplaying of FC’s unreliability and faults and the overhyping of its potential created the environment for Stubblefield to believe she was communicating with D.J., as well as for all the scandals and dashed hopes in the United States over the past 25 years. The evangelists for FC act in bad faith. If they continue promoting FC as they have, further scandals are inevitable.

* * *

Facilitated communication was invented in Australia in the 1970s by Rosemary Crossley while she was a teacher at St. Nicholas Hospital. Her 1980 memoir of those experiences, Annie’s Coming Out—purportedly co-written with facilitated cerebral palsy patient Annie McDonald—was made into a film in 1984. Syracuse ethnologist Douglas Biklen took an interest in Crossley’s work in the late 1980s and brought FC to the United States in 1990. It quickly made a splash, as noncommunicative disabled patients seemed to pass into full participatory life, leading University of California-San Diego education professor Anne Donnellan to declare, “Perhaps Prometheus’ gift of fire to mankind provides the most fitting metaphor for the advent of FC in the worlds of people without speech.” This fervent rhetoric is not unusual. Crossley describes the FC craze in America in her 1997 Ph.D. dissertation:

In August 1992 I went to Syracuse University to teach a course in augmentative communication. This gave me the chance to observe the FC phenomenon at first hand. Parents whose children could not speak, and who had been told nothing could be done, were desperate for help. Teachers and therapists working with people who could not speak wanted to help. They all flocked to lectures and workshops, and they went home and tried to facilitate communication. Those who could not get to workshops picked up what they could from the newspapers or the television coverage and improvised. It is scarcely surprising that their lack of detailed information on what, why, how and with whom led to mistakes and misapprehensions.

Crossley’s simultaneous move of claiming credit for FC’s appeal while blaming its scandals on people doing it wrong has become the standard two-step of FC proponents.

Controlled tests soon showed that messages were coming from facilitators instead of subjects, and some of the individual stories were even more damning. A Frontline PBS special, “Prisoners of Silence,” covered the 1992 case of false sexual assault allegations generated through FC. It sent FC into the shadows. Yet in an eerily similar 2007 case, a man was arrested and spent 80 days in jail after his autistic daughter supposedly accused him of rape via FC.

In 2012, Janyce Boynton, a former facilitator who obtained some of these false allegations, wrote a powerful and harrowing account of her credulity and disenchantment, “Confessions of a Former Facilitator,” describing how powerful her convictions were and how they led her to abandon skepticism. She gives this informed warning:

Knowing what I know today about FC, I would not allow a single word to be typed on a keyboard on behalf of a child without first testing the facilitator in a controlled environment away from the supportive gaze of other believers. … We cannot erase the damage we have caused by our actions, but we can take responsibility for our part in perpetuating the myth of FC. It is time to put a stop to this practice that adversely affects the very people we set out to protect.

In The Science and Fiction of Autism, psychologist and autism specialist Laura Schreibman writes, “FC is truly unusual in that it enjoyed tremendous popularity and widespread use before it was ever put to the scrutiny applied to other new treatments … akin to widespread use of a brand-new vaccine or drug before it has passed rigorous testing and approval by the FDA.”

FC has never been accepted by the medical or psychological communities (it’s been called the “cold fusion” of autism therapies). Dozens of professional organizations have specifically issued statements against its use, including the American Psychological Association, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, and the International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Clinical psychologist Jerome Sattler categorically states in his standard Foundations of Behavioral, Social, and Clinical Assessment of Children: “Under no condition should you use facilitated communication to interview a child with ASD [autism spectrum disorder]” (emphasis mine).

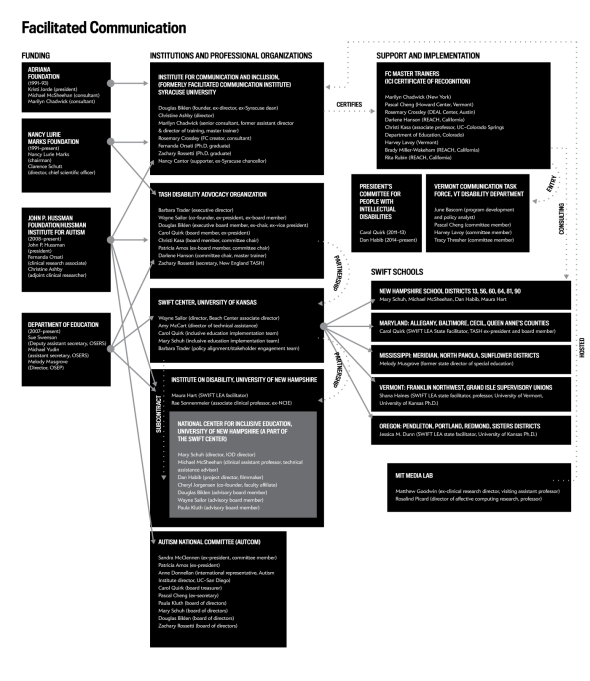

But FC found a home in education departments. Douglas Biklen’s Facilitated Communication Institute (recently renamed the Institute on Communication and Inclusion) at Syracuse, which offers training programs in FC, is the center of FC activity then and now. FC advocates are funded in large part by two private foundations that have each donated millions, the Nancy Lurie Marks Foundation and the John P. Hussman Foundation. Advocates have gradually penetrated into the public school system, the autistic community, and even the President’s Committee on Intellectual Disabilities. Biklen himself was appointed Dean of the School of Education at Syracuse in 2005—over strong objections from many academics—possibly relating to Syracuse’s then-Chancellor Nancy Cantor’s enthusiastic approval of FC. Non-academic support for FC is generated through sympathetic organizations such as the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps (also known as TASH), the Autistic National Committee (AutCom), and the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN), which all parrot the FC party line to varying degees, as well as propaganda films for FC like 2005’s Autism Is a World, co-produced by Biklen. Nonprofits help fund institutes like the one at Syracuse, while the FC supporters at those institutes serve on the boards of those nonprofits.

Axel

The science of FC remains as sketchy as ever: A comprehensive 2014 article confirms that little new evidence has emerged to support FC even as more has stacked up against it. Biklen pointed me to a 1996 study that claims to support FC’s effectiveness, but he grossly overstates its case. In an attempt to demonstrate “message passing,” researchers showed words to FC subjects that their facilitators could not see, then had the facilitators help the subjects report the word they had just been shown. As psychology professor James Todd points out, the overall failure rate is 90 percent, “suggesting that facilitators were guessing.” In response to criticisms, Biklen told me, “That could show the fragility of the method, but it could also show the fragility of the research situation.”

Biklen’s Syracuse institute attempts to cast doubt on such methods of testing for “authorship,” or whether the disabled person being guided by a facilitator is really responsible for the content of FC messages. He insists, “it is crucial that the [FC subject] learns means of demonstrating authorship, for example by learning to pass messages,” even as he writes elsewhere, “Some of the so-called tests of authorship of FC have been oppressive to people with disabilities,” and “research tests could intrude upon and upset the communication process.” Such authorship tests are rarely performed rigorously, and such controlled experiments are even termed “inhumane” by FC advocates like Institute on Communication and Inclusion director Christine Ashby, Biklen’s protégé and successor. It remains an unanswered question why these tests are so difficult and oppressive when subjects like D.J. are supposedly writing papers and presenting them at conferences within a year or two of starting FC.

Claims of “stressful environments” and “confrontational testing” are very much akin to the excuses psychics like Uri Geller use when they cannot replicate their spoon-bending feats under controlled laboratory conditions. In the early 1990s, skeptic James Randi performed his own tests on FC users at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, obtaining predictable results like a facilitated message saying, “I don’t like this man from Florida. He is upsetting my facilitator. Send him home.” Randi still has an unclaimed $1 million prize for a successful demonstration of FC.

Biklen blames FC scandals on bad facilitators who fail to follow his institute’s “best practices.” But he approved of a video at the Bay Area’s Hope Technology School featuring pediatrician Dave Traver (who appeared in the pro-FC documentary I Want to Say), in which a disabled student’s hand is blatantly guided by a facilitator’s wooden stick. “Of course there will be questions about authorship,” Biklen told me, without giving an answer as to why FC advocates appear indifferent to such questions to the point of gross negligence.

FC advocates often point to individual case studies over statistical evidence, appealing to the inspiring sight of a supposed success story. But the standards are so low as to be unconvincing. Peyton Goddard, an autistic woman, has written a book, I Am Intelligent, via Facilitated Communication, but a video on her own Web page shows facilitator Darlene Hanson firmly holding Goddard’s arm even as Goddard looks away from the screen while “typing” (at 0:47 in particular in the video below). Hanson is not a random facilitator and Goddard not a random patient either; Hanson co-authored a 1996 paper that Biklen and others cite as containing the strongest research in support of FC, while Biklen and others hold up Goddard as an FC success story. (Biklen refused to comment on this particular video.) If Hanson, whom Biklen and his institute deem a “master trainer” of FC, still can’t practice FC correctly, how common can “correct” FC practice be? And if she is practicing FC correctly, then the method is bunk.

Stubblefield’s experience in FC developed not professionally but personally: Her mother, Sandra McClennen, has been a vocal FC advocate for many years, and was involved in one of FC’s other major controversies, the Wendrow case. That is the 2007 case in which false accusations obtained through FC sent a parent to jail for 80 days for allegedly raping his 14-year-old daughter. (The case fell apart when the girl could not repeat the allegations unless her facilitator heard the question she was asked.) McClennen, who had introduced the Wendrow family to FC, appeared as a prosecution witness, even as she cast doubt on the accusations and discredited the skills of the facilitator who had obtained the accusation. The alleged victim “has never been very good at accurately conveying information about past events. … There’s, like I said, a lot of room for [facilitator] influence, and we have to constantly worry about that.” Even this is an uncommon admission.

Though Stubblefield’s academic work was in philosophy of race, she published an article in 2011 on facilitated communication in Disability Studies Quarterly—the same issue, in fact, in which D.J.’s purported article appeared. Titled, “Sound and Fury: When Opposition to Facilitated Communication Functions as Hate Speech,” Stubblefield’s article is a ripping, though not especially rigorous, attack on opponents of FC, accusing them of hate speech and intimidation. Her main target is FC detractor James Todd, whom she criticizes for a litany of sins, including questioning the credentials of FC advocate Sandra McClennen. Nowhere in the paper does Stubblefield identify McClennen as her mother or reveal that Todd had testified for the defense in the Wendrow case. (When asked, Society of Disability Studies Chair Brenda Jo Brueggemann, responsible for oversight of the Disabilities Studies Quarterly, said only that the board is “paying significant attention to the issues” about this 4-year-old paper. After an FC critic called for DSQ to take down D.J.’s paper, however, Brueggeman said that his “ignorance and hubris is overwhelming.”) The article gives some indication of the depth of Stubblefield’s investment and involvement in FC, which concurrently was giving rise to her sexual relationship with D.J.

Stubblefield writes: “Anti-FC rhetoric that presumes what must be proved—the intellectual impairment of FC users—functions as hate speech because it calls into question the meaningfulness or worthiness of consideration of FC users’ communication.” The tragic irony is that Stubblefield had it exactly backward. It is pro-FC rhetoric that presumes what must be proved: that the communication it produces is actually communication. Any careful, thoughtful researcher has the duty to gain certainty on that point before even attempting to gauge the intellectual capacity of an FC user. The judge in Stubblefield’s trial recognized this when she disallowed expert testimony on FC: Pseudoscience doesn’t generate reliable and trustworthy knowledge, which is what an expert must provide.

One of the most important lessons from the very checkered history of science is that common sense, emotional instincts, conventional wisdom, and even our own observations are often more likely to be wrong than right, and so extreme caution, from double-blind studies to replication, must be taken before we collectively agree on the validity of a particular therapy or method. To start up an institution that rejects the existing communal discourse of skepticism and debate, as FC has done, is to abandon any claim to certainty.

Facilitated communication has created a domain of surrealism for anyone entering it anew. I can’t say I’ve ever had conversations quite so strange as I did in investigating this story. Multiple FC proponents told me that there are a large number of people who believe that telepathy underpins FC. They said people are discouraged from talking about psychic powers for fear of being blacklisted by Biklen and his associates. When interviewing Mary Schuh of the University of New Hampshire’s Institute on Disability, an FC advocate who promotes FC in public schools and consults on pro-FC films, I was left nonplussed after exchanges such as this:

Why do you utilize a very controversial and generally unproven approach?

Schuh: We’re offering FC training because there’s a huge demand for it. Hundreds of people have been asking for evaluations that include it.

What if hundreds of people came demanding leeches as a treatment for autism?

Schuh: If a hundred people came here and demanded leech treatment, I think there’d be people here saying to take a look.

What if people came demanding astrological treatment for autism?

Schuh: Astrology? No, because we don’t have anyone who has high-enough quality and training in order to deliver that.

There are FC practitioners and advocates who believe telepathy plays a role in FC. Do you believe telepathy is a part of facilitated communication?

Schuh: Telepathy? I have no comment on that. I couldn’t say yes, I couldn’t say no. It’s not part of the practice of the method. It’s a hard place for me to go to.

Biklen seemed strangely detached from these controversies when I spoke with him. He repeatedly tried to shift the vocabulary of the debate to terms more favorable to him, rejecting words like test, reliable, and certainty as though they were inappropriate to the discussion. Most troublingly, while even the most diehard opponents of FC expressed sympathy for D.J., Stubblefield, and both of their families, Biklen seemed disconnected from anything except the reputation of FC—and presumably his own reputation and legacy. It is this oppositional, cloistered mentality that marks out FC in general. Biklen repeatedly pointed to Sue Rubin, an autistic FC user who may type independently (though videos consistently show Rubin’s facilitators holding—and moving—Rubin’s keyboard). But even granting that Rubin’s communications are authentic, one happy case does not counterbalance the entire weight of evidence against FC. Biklen blamed a small band of critics for the fact that so many medical and scientific organizations oppose FC, as well as those who don’t follow “best practices.” When asked about the tragic case of Gigi Jordan and the death of her son, Chadwick, who had trained Jordan, told me, “She was not using [FC] correctly.” The terrible consequences of “incorrect” FC use make it unconscionable to hype FC to parents desperate to communicate with their children.

A typically effusive presentation by Harvey Lavoy and Marilyn Chadwick, hosted on a Vermont government server, makes no mention of verifying authorship or best practices—just the inspiring possibility that disabled people may become autonomous speakers. The Institute on Communication and Inclusion lists Lavoy and Chadwick alongside Darlene Hanson and Rosemary Crossley among its “master trainers” of FC. The “master trainer” is not a degree—no such credential exists for FC specifically. Rather, it is a “level” awarded to those who have, in Chadwick’s words, “given their dedication, time, and energy” to FC. A set of facilitators at Institute on Communication and Inclusion awarded themselves the title in the mid-1990s and now determine who may become a new master trainer. Only a handful have been added in the last 20 years, a sign of the ICI’s desire to maintain hegemony over the practice of FC.

A core group of FC practitioners and proponents, based primarily in the Northeast, are commonly seen together at FC-sympathetic conferences like the annual ICI-sponsored Autism Summer Institute, which caused controversy in 2011 when it was hosted by the MIT Media Lab through grants from the Hussman and Nancy Lurie Marks Foundations. The conference returned to the friendlier climates of University of New Hampshire in 2012, Syracuse in 2014, and the University of Northern Iowa in 2015. The core group of attendees (Biklen, Crossley, acolytes, and master trainers) has remained constant. A quieter group of supporters, including the Department of Education’s Sue Swenson, avoid blatantly pro-FC events and congregate at conferences such as the PEAK Parent’s Center’s Conference on Inclusive Education in Colorado Springs, which do not mention FC explicitly but are packed with FC advocates.

Even the more established supporters are evasive, however. In interviews, FC proponents, particularly the professors, tried to play Calvinball with me, avoiding words and trying to redefine the debate. While opponents would concede anecdotal “successes” while citing the sheer unreliability and mysticism surrounding FC, supporters’ claims for their cause were frequently inflated and disingenuous. When asked if FC is reliable, Biklen told me, “For some people it’s highly reliable,” a misleading way of saying “no.” Biklen and others termed FC a valid form of Augmentative and Alternative Communication, then hedged when I cited the International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication’s position statement in 2014 declaring, “The weight of evidence does not support FC and therefore it cannot be recommended for use in clinical practice.”

Most troublingly, Biklen seemed nearly indifferent to the possibility of words being put into the mouths of the disabled, saying that the rarely reached goal of “independent typing” was more important than the veracity of communication prior to that. (As one FC proponent told me, “Saying that the goal of FC is independent typing is like saying that the goal of learning violin is playing Carnegie Hall.”) Biklen preaches inclusion even as his method silences and ventriloquizes those he supposedly advocates for. “It’s been useful to some people,” Biklen finally said, while being unwilling to admit that it has been useless, deceptive, and sometimes destructive to far more.

* * *

Though scandals have dogged Facilitated Communication pretty much since its inception, it has not died out as most miracle cures tend to do. Its persistence in spite of both scientific opposition and scandals is a testament to FC’s skill at rewriting and erasing its history.

One early piece of embarrassing FC history involved facilitator Michael McSheehan, who trained in Facilitated Communication at Syracuse and joined the University of New Hampshire’s Institute on Disability in 1993. McSheehan mediated remarkable messages from the beyond from an autistic girl named Adriana Rocha. The messages, delivered in 1991, told of her past lives, Jesus, angels, and a coming apocalypse. The facilitated communication was achieved not just through a keyboard, but through telepathy. Adriana’s mother, Kristi Jorde, was a major funder of FC through her Adriana Foundation. Jorde’s book, Child of Eternity was ostensibly co-written with Adriana through facilitated communication. As Jorde tells it:

Not long after Adri first began facilitating regularly with Michael, she began to demand that he share with us the telepathic messages he was receiving from her. While he was willing to do this for her, he wanted to make certain that their communications remained accurate. So, together, they worked out a form of telepathic facilitation. … She would type the first letter of a word, and if Michael understood the word telepathically, he’d say it aloud. Adri would then hit the space key to indicate that he was correct. Sometimes, oddly enough, as in the case of the word synergy, Michael understood the word telepathically but didn’t know the meaning of it so we had to stop our conversation and define it for him.

It’s an amazing experience to be part of a telepathic conversation. Michael and Adri modeled for us the incredible potential of human communication.

Jorde’s book included long passages from Adriana, such as:

ADRI: MOST OF MY SKILLS ARE TELEPATHIC. I GET ALL PEOPLE’S IDEAS. I CAN SEE THROUGH HUMAN’S [sic] EYES. MOSTLY I “TUNE IN” TO FIND OUT INFORMATION ABOUT THE WORLD. I TALK WITH MY GUIDES TO SUMMARIZE PRECOGNITION…I CHOOSE TO BE AUTISTIC FOR MY SOUL.

Adriana reveals herself to be the reincarnation of Jesus’ disciple John and encourages Jorde to have past life regression. Working with Robin Casarjian, Jorde discovers that she herself was a soldier in Gethsemane who got bruised by Peter in order not to have to participate in the crucifixion. (McSheehan could not be reached for comment for this article.)

Biklen and Crossley cut off contact with both Jorde and the Adriana Foundation sometime around 1993, scrubbing the foundation’s name from their materials in what appears to be an attempt to distance themselves from the taint of the paranormal. Jorde was last seen practicing quantum healing hypnosis in Florida. Her daughter, FC success story Adriana Rocha, is a “Nonverbal Autistic Master” and “Wisdom Keeper of the New Earth” at the New Earth Academy.

Psychic facilitator McSheehan remains at New Hampshire’s publicly funded Institute on Disability, where he is a clinical assistant professor, despite possessing only a bachelor’s degree. He is peddling the same miracles on public money, only without the telepathy and the angels. Very little has changed after 20 years when we see him in a short film called Axel, publicly funded by the Department of Education’s National Center and State Collaborative and distributed to public schools by the public University of New Hampshire as part of an education kit for the film Who Cares for Kelsey, frequently used to support the Department of Education’s Schoolwide Integrated Framework for Transformation program.

The film follows the usual FC narrative, though without ever using the term “facilitated communication.” McSheehan arrives at Idlehurst Elementary School in Somersworth, New Hampshire, and fifth-grader Axel Cortes, previously thought to be non-verbal, shortly reveals himself to be bilingual—though as autism specialist Lisa Brady, who worked with Axel, told me, he only ever used Spanish when a Spanish speaker was facilitating him. “Axel’s now on the path to college,” McSheehan announces, after his work is done. A look at the video reveals its defects: Axel’s hand is being guided by the pathologist, Axel looks away from the screen, and the whole thing is carefully edited to obscure the scam. Harvard’s Howard Shane documented the tricks and deceptions for me in detail, concluding, “They only made a few mistakes in the editing, but the truth does come out.”

Brady realized that Cortes was not the author of these messages and that the entire film had been cooked, but she claims her whistleblower attempts got her first warned, then threatened, and eventually transferred and fired. She alleges she got little support from her union, the New Hampshire National Education Association, which partly funded the film. Idlehurst principal Dana Hilliard refused comment and directed me to Superintendent Toni Mosca, who did not return calls or emails; neither did the school board chairs. If Axel is typing independently today, no one was willing to tell me—most won’t talk about him at all. McSheehan tells an eerily similar story about “Charlie” in a 2007 Institute on Disability newsletter, except there he admits he does what Brady accuses him of doing with Axel: Charlie’s “hundreds of pre-programmed messages” in his voice device are written by the team, not by Charlie. At the time, the Institute on Disability was working under an $825,000 subcontract from the Department of Education to provide McSheehan’s type of “services” to public schools.

Facilitated Communication’s low profile belies the distressing advances its proponents have made in public schools. As FC facilitator and advocate Pamela Block told me, “There are a lot of people very loudly detracting but a lot of people very quietly implementing it in schools,” including in New Hampshire, Maryland, Oregon, and Mississippi. The main vector for this push is the Department of Education–funded Schoolwide Integrated Framework for Transformation (SWIFT) Center, which employs McSheehan, Schuh, and other FC proponents in central roles. When Secretary of Education Arne Duncan announced the grant to create SWIFT, he cited “30 years of research and experience” backing the program’s ideas, but a major chunk of that research is by FC supporters like McSheehan. The Axel film packages FC into the SWIFT program, as do things like a SWIFT blog post supposedly written by 12-year-old FC user Grant Blasko, which reads more like a parent’s fantasy than any 12-year-old’s reality. (“Missed opportunities go unnoticed most times,” he writes.) A scathing assessment of a 2013 FC pilot program by the Montgomery County Schools’ Office of Shared Accountability in Maryland recommended abandoning attempts at “communication” with nonverbal students, yet SWIFT is still in the implementation stages at other Maryland schools. Maryland-based SWIFT executive team member, former TASH President, and Autistic Self Advocacy Network Treasurer Carol Quirk is pushing for it, with assistance from the ubiquitous Michael McSheehan. Maryland is quickly becoming a new hub for FC activity due to the presence of the wealthy pro-FC Hussman Institute for Autism at the University of Maryland’s BioPark. The number of organizations multiplies, but they always connect back to the same core group, most of whom occupy several roles across multiple pro-FC organizations.

New Hampshire Gov. Maggie Hassan and Commissioner of Education Virginia Barry accepted $250,000 from the SWIFT Center to pay for SWIFT to be adopted in New Hampshire public schools. Hassan claims the pro-FC films showcase “innovative educational approaches” which are part of an “educational revolution.” Barack Obama appointed Axel director Dan Habib, who is a project director at New Hampshire’s Institute on Disability, to the President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities in 2014, another example of prestige and money quietly accruing to FC advocates. Habib also received a Civil Rights award from the New Hampshire National Education Association in 2012, which was simultaneously funding his films. McSheehan, Habib, and Mary Schuh (who is listed as an adviser on Habib’s films) together also form the core staff of University of New Hampshire’s SWIFT subcontractor, the National Center for Inclusive Education (NCIE), which co-produced Axel. In a move characteristic of FC’s quiet nepotism, through NCIE, Schuh, McSheehan, and Habib have brought FC consultants like Pascal Cheng, another Biklen-approved “master trainer” from Syracuse, to train New Hampshire teachers in FC. NCIE received an $825,000 federal subcontract as part of the SWIFT Center. NCIE’s advisory board contains Douglas Biklen, as well as a number of other FC supporters. Also on NCIE’s board is the University of Kansas’ Wayne Sailor, overall director of the SWIFT program. Sailor also founded the FC-supporting organization TASH. While TASH has very little influence in academic circles, McSheehan gave the 2014 TASH keynote in collaboration with the Department of Education’s Michael Yudin, lending TASH and FC more legitimacy. TASH is now a member of the SWIFT Policy Team and conducts congressional briefings.

Holly Allen

At the Department of Education, Yudin’s deputy Sue Swenson, who has hosted TASH fundraisers with Carol Quirk and whose son was a longtime user of facilitated communication, and director of the Office of Special Education Programs Melody Musgrove liaised between the DOE and SWIFT alongside Yudin himself. It is no coincidence that New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maryland, all hubs for FC activity, are three of the five pilot states for SWIFT. Musgrove, wife of former Mississippi Gov. Ronnie Musgrove, worked at the Mississippi Department of Education for many years, likely explaining its selection as a fourth SWIFT state. Swenson, who has criticized academics for being too conservative and cautious in disability education, worked in disability management in Maryland for many years, while Yudin has held positions in the offices of former Vermont Sen. Jim Jeffords and former New Hampshire Gov. Jeanne Shaheen.

With the exception of Sailor, none of the leaders involved in SWIFT have doctorates in psychology, medicine, or any of the disciplines that have repeatedly and consistently rejected FC as an effective method. TASH appointed Jenny Stonemeier to be their Education Policy Director for SWIFT (a position funded by the federal SWIFT grant), yet Stonemeier has no credentials in psychology or education beyond being a “Board Certified Music Therapist.” This lack of qualifications may spell trouble for SWIFT schools. Parents do not want their children subject to a school plan developed by a psychic (McSheehan), an educator open to astrology (Schuh), and a cinematic charlatan (Habib), and which contains dangerous and unreliable practices explicitly rejected by dozens of professional organizations. If FC produces a sexual abuse allegation in one of these schools, or if an FC user gets harmed or harms another child through educational malpractice, what will be the result? Aside from the sheer human cost, taxpayers will have to shoulder the huge liability costs when SWIFT and FC fall apart in court. I would immediately remove my child from any school that implements SWIFT and ask that my school board explicitly denounce FC, and I would advise any other parent to do the same. Pseudoscience is contagious.

Beyond spending a great deal of time in FC-friendly environments, Swenson, Musgrove, and Yudin all have social connections to SWIFT’s and TASH’s FC advocates on Facebook, and consequently the funding and selection process for SWIFT and NCIE merits closer scrutiny. I am deeply skeptical of TASH and SWIFT’s claim that the five states “were selected based on a rigorous set of criteria that included multiple sources of data,” and there needs to be more transparency about how the DOE gave such an outsized $24.5M grant to the University of Kansas, their largest grant ever. Musgrove, for her part, has signaled that the DOE will “essentially ignore IEP [Individualized Education Program: the written instructions guiding a child’s special education] violations,” according to a post on education expert Diane Ravitch’s blog—violations like the use of facilitated communication on a student with whom it hasn’t been approved. Brady, in fact, has alleged numerous other misdeeds at her school, including facilitated communication being used unlawfully with students who didn’t have it in their IEPs. In other words, Brady’s report is not an isolated anomaly, but a direct consequence of actions taken by federal DOE employees.

Another New Hampshire public school teacher, who chose to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal, confirmed to me that FC is being pushed aggressively in New Hampshire’s schools. “At faculty presentations, they use films like Axel to argue that the method and model works.” The teacher claimed to know of other school employees being forced to use FC without it being part of their students’ IEP. “Often, IOD’s SWIFT team has presentations across New Hampshire where they herald a ‘facilitator’ with no formal educational training as exceptional, just because they’re using FC. They present this facilitator as the ‘savior’ of the child.” The teacher, who pointed to Schuh, Habib, and McSheehan as leading the FC charge, told me that no authorship verification tests are ever performed, and that the top-down mandate of regular education classrooms for all in SWIFT schools is causing a significant drop in teacher morale. “There’s a huge silenced majority of people who feel impotent to say anything for fear of losing their employment.” The history of FC indicates that this silence is sure to be catastrophic.

One University of New Hampshire person not involved in any of this is Stephen Calculator of UNH’s College of Health and Human Services, an early proponent of FC who left the movement in the late 1990s after studies convinced him that FC didn’t actually help its users. Despite having people far more specialized in the science of autism than the Institute on Disability, the IOD and the CHHS have very little to do with one another. Howard Shane put it more bluntly: “As a resident of New Hampshire, I’ve always been offended by them having an institute that supports FC.” It also raises the question of why the DOE and SWIFT are working with McSheehan instead of Calculator. (Calculator himself had no comment on FC, the IOD, or SWIFT.)

It’s not just schools. In Vermont, the ICI-affiliated June Bascom, a program development and policy analyst for Vermont’s Division of Disability and Aging Services, heads the Vermont Communication Task Force, which is stacked with FC practitioners and advocates, and the task force’s Web page links to FC propaganda by committee members and FC “master trainers” Harvey Lavoy and Pascal Cheng (who also consult with SWIFT), who both participated in the Biklen-funded film Wretches and Jabberers. The Vermont Communication Task Force page’s sole external link is to Biklen’s ICI.

In researching this article, I looked at many, many FC “successes” trumpeted by leading FC luminaries. Enough were clearly bunk that they put into question all the others. Indeed, FC sustains itself these days only through obfuscation. Without whistleblowers, there would be little to draw attention to the seemingly innocuous SWIFT Center. FC advocates have never faced real oversight, and they have grown a thicket of misinformation, innuendo, wishful thinking, and cultish bullying around them to prevent it.

Citing FC as well as the infamous fraudulent research linking vaccines to autism that helped bring back measles, James Todd pointed to the culture around autism treatments as chronically credulous: “It’s a giant fad magnet and the intellectual standards for publishing on autism are really low. You can get away with talking about things that are at a level of pseudoscience that would never fly in any other discipline.”

This lack of rigor contaminates positive advocacy as well. The ongoing case of Sharisa Kochmeister, an autistic FC user who was taken from her parents in March and put in a nursing home by Colorado’s Jefferson County. The cloud of unreliability surrounding FC makes it that much more difficult to determine whether the county was protecting Kochmeister or violating her rights. If we cannot trust in abuse allegations obtained through FC (and we can’t), we can’t trust in Kochmeister’s speech obtained through FC. FC’s presence tragically puts into question what Kochmeister’s voice is saying, or if indeed we are hearing her at all.

FC has left a long trail of forgotten victims, many of them extremely vulnerable, who go unnamed even as FC advocates trumpet a handful of dubious success stories. FC is uncommonly dangerous, however, because of its current institutional push, of which SWIFT is only the most visible example. As Todd said, “These are the most vulnerable people in our society, and the last thing they need is a pseudoscientific treatment foisted on them by people who can’t demonstrate its efficacy.” The damage must end.