When Adam Lanza killed 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, politicians and lobbyists blamed our broken mental health system. Lanza’s mother had told people that he suffered from Asperger syndrome and sensory processing disorder, but it’s unclear whether he ever received adequate treatment for these or other conditions that may have gone undiagnosed. Would things have been different if a professional had intervened as Lanza withdrew from society and descended into a confused psychological hell?

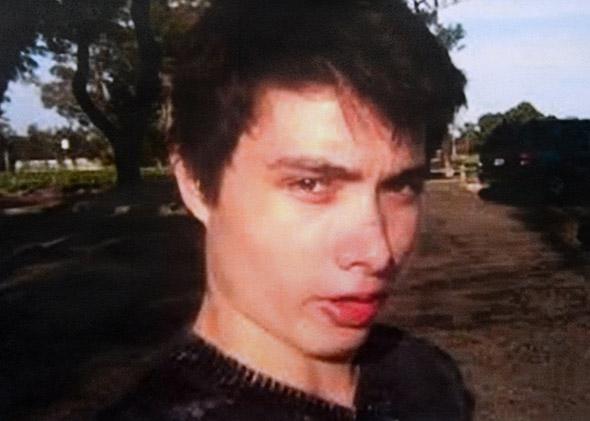

We now have a tentative answer: No. Last week, Elliot Rodger killed six people in Isla Vista, California. Like Lanza, Rodger was mentally ill. Unlike Lanza, Rodger had extensive contact with both mental health professionals and law enforcement authorities. Rodger’s parents had long been concerned about his erratic behavior. A lawyer for Rodger’s father said Elliot Rodger had been seeing multiple therapists. Santa Barbara police visited his apartment six months before the shooting but found nothing in his demeanor to be concerned about.

Adam Lanza’s story made me sad for everyone involved—including, in a way, Lanza himself, who never got the help he obviously needed. Elliot Rodger’s story makes me feel despair and hopelessness. Rodger met with trained mental health professionals, the people we rely on to identify dangerously disturbed individuals, and they apparently failed to perceive the depth of his problems. Police officers, who spend their days dealing with violent, troubled people, described Rodger as “polite and courteous.”

The Isla Vista shooting calls into question the reasonableness of our expectations. Are we asking parents, teachers, mental health professionals, and police officers to be mind-readers or see into the future? Can even a trained professional reliably distinguish a troubled person from a dangerous person? I posed some of these questions to E. Fuller Torrey, psychiatrist, founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center, and author of American Psychosis: How the Federal Government Destroyed the Mental Illness Treatment System.

Slate: What signs should parents look for that differentiate a child who needs help coping from one who presents a danger to others?

Torrey: As a general rule, young adults who develop erratic behavior do so in response to either substance abuse or early symptoms of psychosis (schizophrenia or bipolar disorder). The most important thing to look for is a marked change in behavior: previously outgoing with lots of friends, now spends most of his/her time in bedroom alone; or a dramatic drop in school grades.

Do therapists receive adequate training to recognize potentially dangerous patients?

“Therapist” usually indicates a psychologist or social worker, although it may also include people with other degrees, including those obtained by mail order. The training of therapists, and their ability to evaluate an individual such as Elliot Rodger, thus varies widely depending on their training. California seems to have more than its share of mail order degree therapists.

What strategies do people use to cover mental illness when confronted by parents, social workers, teachers, and law enforcement? Are there questions authorities should ask to identify a person attempting to conceal mental illness?

Many individuals who are psychiatrically disturbed are able to “hang it together” for a few minutes when confronted by a police officer, judge, etc. I have had very psychotic patients appear quite rational for 10 minutes in a courtroom by focusing their mind. Patients with Parkinson’s disease can similarly suppress their tremor briefly by focusing their mind on it. Thus, it is unrealistic to expect a police officer to make a clinical evaluation, and such evaluations should include a mental health professional.

In Vancouver, at one time, they routinely had a psychiatric nurse go with the police officer to do such evaluations. A psychiatric nurse would be less threatening, could take [the suspect] aside and ask open-ended questions. (For example: “What is the worst thing that has happened to you in the last month?” or “If you did decide to kill yourself, how would you do it?”) The nurse could also, with his permission, use a cellphone to call his mother (or whoever raised the alarm), and/or his therapist at that time to get more information. Mental health professionals are more likely to pick up subtle clues that something is not right. To expect law enforcement officers to do this is unfair to them; they are not trained to do so and this is not why they became a law enforcement officer.

Under what circumstances can a family member, social worker, or law enforcement officer have a person involuntarily committed because they represent a danger to society? With the recent spate of shootings perpetuated by people with known mental illness, do those laws need updating?

Commitment laws vary by state. Details about the law in each state can be found on the website of the Treatment Advocacy Center. A rating of state commitment laws was published in February 2014. California’s commitment law is among the strictest, thus making it very difficult to involuntarily commit an individual like Elliot Rodger for evaluation. State laws need to be improved.

Have we allocated the proper resources to help identify, treat, and potentially confine people whose mental illness makes them dangerous? If not, where do resources need to be directed? Are there enough facilities to treat these people?

The answer is a resounding no. In California, like most states, we have closed 95 percent of public psychiatric beds. Even if a decision had been made to involuntarily commit Mr. Rodger for an evaluation, it would have been extremely difficult to find a bed. The public mental illness treatment system is completely broken. Rep. Tim Murphy in Congress has held hearings on the broken mental illness treatment system for the past year and produced a good bill which could improve it: The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act. Every member of Congress should be supporting it.

Read the rest of Slate’s coverage of the UC–Santa Barbara shooting.