From the outside, my eating disorder looked a lot like vanity run amok. It looked like a diet or an obsession with the size of my thighs. I spewed self- and body-hatred to friends and family for well over a decade. Anorexia may have looked like a disorder brought about by the fashion industry, by a desire to be thin and model-perfect that got out of hand.

Except that it wasn’t. I wasn’t being vain when I craned my neck trying to check out my butt in the mirror—I truly had no idea what size I was anymore. I was so afraid of calories that I refused to use lip balm and, at one point, was unable to drink water. I was terrified of gaining weight, but I couldn’t explain why.

As I lay in yet another hospital bed hooked up to yet another set of IVs and heart monitors, the idea of eating disorders as a cultural disorder struck me as utterly ludicrous. I didn’t read fashion magazines, and altering my appearance wasn’t what drove me to start restricting my food intake. I just wanted to feel better; I thought cutting out snacks might be a good way to make that happen. The more I read, the more I came to understand that culture is only a small part of an eating disorder. Much of my eating disorder, I learned, was driven by my own history of anxiety and depression, by my tendency to focus on the details at the expense of the big picture, and by hunger circuits gone awry. The overwhelming amount of misinformation about eating disorders—what they are and what causes them—drove me to write my latest book, Decoding Anorexia: How Breakthroughs in Science Offer Hope for Eating Disorders.

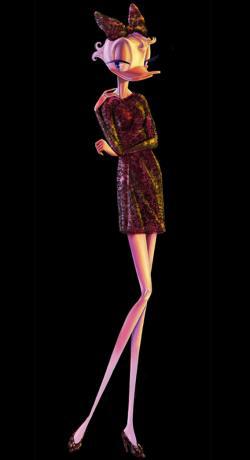

Efforts to fight eating disorders still target cultural phenomena, especially images of overly thin, digitally altered models. Last month, the Academy for Eating Disorders and the Binge Eating Disorders Association issued a press release condemning the high-end department store Barneys for giving beloved Disney characters a makeover. Minnie Mouse and Daisy Duck were stretched like taffy to appear emaciated in honor of Barneys’ holiday ad campaign. The eating disorders groups wrote (PDF):

Viewership of such images is associated with low self-esteem and body dissatisfaction in young girls and women, placing them at risk for development of body image disturbances and eating disorders. These conditions can have devastating psychological as well as medical consequences. This campaign runs counter to efforts across the globe to improve both the health of runway models and the representation of body image by the fashion industry.

All of which is technically true. But when you look at the research literature, several studies indicate that environmental factors such as emaciated models are actually a minor factor in what puts people at risk of an eating disorder. A 2000 study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry found that about 60 percent (and up to 85 percent) of a person’s risk for developing anorexia was due to genetics. A 2006 follow-up study in the Archives of General Psychiatry found that only 5 percent of a person’s risk of developing anorexia came from shared environmental factors like models and magazine culture. A far greater environmental risk (which the study estimated constituted 35 percent of someone’s risk of anorexia) came from what researchers call non-shared environmental factors, which are unique to each individual, such as being bullied on the playground or being infected with a bacterium like Streptococcus. (Several very small studies have linked the sudden onset of anorexia and obsessive-compulsive symptoms to an autoimmune reaction to strep infections.)

Eating disorders existed long before the advent of supermodels. Researchers believe the “starving saints” of the Middle Ages, like Catherine of Siena, had anorexia. Reports from ancient history indicate that wealthy Romans would force themselves to vomit during feasts, to make room in their stomachs for yet another course. In modern times, anorexia has been reported in rural Africa and in Amish and Mennonite communities, none of which are inundated with images of overly thin women. Nor does culture explain the fact that all Americans are bombarded with these images but only a very tiny portion ever develop a clinical eating disorder.

Frankly, I think the Barney’s creation of Skinny Minnie and her newly svelte compatriots is ridiculous. They look absurd and freakish. I think we should be aware of and speak out against the thin body ideal, the sexualization of children, and the use of digitally altered images in advertising. I think we should do this regardless of the link to eating disorders. My objection to the AED and BEDA’s response is that it reinforces an “I wanna look like a model” model for how we think of eating disorders. It implies that eating disorders are seen as issues for white, upper-class women, which means that these life-threatening disorders often go undetected and untreated in men, the poor, and minorities.

How sufferers, their families, and our culture at large think about eating disorders sets the agenda for treatment, research, and funding. Until a 2008 lawsuit in New Jersey established that anorexia and bulimia were biologically based mental illnesses, it was legal for insurance companies to deny necessary and lifesaving care. The message to sufferers? You’re not that bad off. You’re just making this up. Get over it.

Too many people can’t. Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric illnesses. Up to 1 in 5 chronic anorexia sufferers will die as a direct result of their illness. Recovery from anorexia is typically thought of as the rule of thirds: One-third of sufferers get better, one-third have periods of recovery interrupted by relapse, and one-third remain chronically ill or die.

Although research into eating disorders is improving, it is still dramatically underfunded compared to other neuropsychiatric conditions. The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that 4.4 percent of the U.S. population, or about 13 million Americans, currently suffers from an eating disorder, and eating disorders receive about $27 million in research funding from the government. That’s about $2 per affected person, for a disease that costs the economy billions of dollars in treatment costs and loss of productivity. Schizophrenia, in comparison, receives $110 per affected person in research funding.

The lack of research funding means that it’s been difficult to develop new treatments for eating disorders and test them in clinical trials. Several types of psychotherapy have been found effective in the treatment of bulimia and binge-eating disorder, although many sufferers have difficulty maintaining recovery even with state-of-the-art treatment. Thus far, no therapies have been clinically proven for adults with anorexia. Because many of those with anorexia are scared of the idea of eating more and gaining weight, they tend to be reluctant to show up for treatment and follow through with a clinical trial. Researchers have found a type of treatment known as family-based treatment, which uses the family as an ally in fighting their child’s eating disorder, to be effective in children, teens, and young adults with anorexia or bulimia.

The message from AED and BEDA is technically correct: More and more children are dieting, whether in response to thin models, obesity prevention efforts, or both. Dieting is potentially dangerous because food restriction can set off a chain of events in a vulnerable person’s brain and body. For most people, diets end after a modest weight loss (and are, more often than not, followed by a regain of the lost weight, plus a few “bonus” pounds as a reward for playing). For the 1 percent to 5 percent of the population that has a genetic vulnerability to an eating disorder, that innocent attempt at weight loss, “healthy eating,” or other situation that results in fewer calories being eaten than necessary, can trigger a life-threatening eating disorder.

However, focusing on purported cultural “causes” of eating disorders leaves out the much bigger, more multifaceted picture of what these disorders are. Eating disorders result from a complex interplay between genes and environment; it’s not just culture. Yet most media coverage of eating disorders focuses on these types of cultural factors. Well over half of the eating disorder stories I see are about celebrities. Celebrities suffer from eating disorders, too, but they are a small fraction of the total number of sufferers out there. Eating disorders aren’t solely about wanting to be thin. They aren’t about celebrity culture or the supermodel du jour. They are real illnesses that ruin lives.