You may have heard that we’re entering an algae farming boom. Biofuel produced by algae reared on greenhouse gases is supposed to replace fossil fuels with a climate-friendly brew. But if you try to refuel your car, tractor, or Cessna using this vaunted energy source, you’ll quickly realize that hype alone cannot stroke an engine. Algae biofuel isn’t for sale. At least, not unless you can get your hands on experimental samples being produced in laboratories. After more than 35 years of federally funded research, the cost of producing algae biofuel is a lichen-covered cliff that separates it from the ocean of cheap fossil fuels.

Despite algae biofuel’s economic shortcomings, though, there’s a feast of good news for supporters of slime-driven climate action. Algae are being cultivated commercially, and in growing volumes. They are being grown in waters enriched with carbon dioxide, climate-changing waste gases that can be pumped into algae ponds from mines, power plants, and factories.

Oil from the commercial harvests isn’t being sold as fuel. It’s ending up inside something more intimate than a rush-hour crowd in a biodiesel bus. It’s sold as food. The oils, proteins, and carbohydrates from farmed green slime are fueling the cells inside our bodies.

Algae is an imprecise word. The spongy plantlike species that we dump into the taxonomic algae bucket don’t all come from a common ancestor. Algae is one of those “you know it when you see it at the end of your fishing line”-type things. Some single-celled strains are microscopic; giant kelps can stretch 200 feet. Humans have eaten some seaweed varieties of algae for countless generations; other kinds of algae poison swimmers at beaches seeped in sewage. Today’s algae include the descendents of some of the first organisms to suck up carbon dioxide, use solar energy to combine the carbon into sugars and proteins, and create our animal-friendly atmosphere by pumping waste oxygen out after photosynthesis. Some algae light up oceans at night in glowing blues or paint them blood-red during the day. Some are carnivorous, preying on passing zooplankton—the microscopic equivalents of hypothetical savanna grasses that grab and devour passing gazelle.

Many algae species occupy the bottoms of food chains. When fish graze on algae, or on zooplankton that fed on algae, they absorb energy that the algae plucked from sunrays, and they lap up the algae’s nourishing fatty acids. These are the same acids that we hanker for when we buy fish oil tablets in hopes of lubricating our weary joints.

“You’ve got a bunch of algae out here, right?” President Obama said during a 2012 energy speech at the University of Miami. The Floridians laughed. They’re accustomed to pollution-fueled algae outbreaks that ruin their beaches and kill their pets. Florida’s lawmakers are considering spending $380 million next year to clean up 38 natural springs—waterholes popular with divers but infested with mats of algae following decades of pollution runoff. More than 100 manatees died in the Indian River Lagoon last summer. Scientists say they were poisoned after eating a type of algae that flourishes in pollution.

Algae can be a formidable environmental foe for the same reason that farming them seems so attractive—because they can prosper with so little. Warmth, sunlight, and nutrient-tainted waters are all they need, and these ingredients are in rich supply in many American states. Gulf of Mexico algae outbreaks fueled by Midwestern agricultural runoff trigger an annual oxygen-depleted dead zone that reached 5,840 square miles last summer. “If we can figure out how to make energy out of that,” Obama continued, “we’ll be doing all right.”

The thing is, we’ve already figured out how to make energy out of that. It’s just that nobody is doing it—not on a commercial scale, anyway. Farming and refining algae biofuel remain economically unviable. By National Algae Association estimates, a company would need to farm 250 acres of algae before it could start turning a profit on biofuel. That could change by 2020, if industry insiders who responded to an Algae Biomass Organization poll turn out to be correct, with growing costs expected to come down.

Meanwhile, Florida-based companies Algae to Omega and Florida Algae, as well as companies like them nationwide, are farming and selling algae-based commodities that have nothing to do with green energy. Instead, they’re selling things that can actually bring in the green.

“Until more federal funding is available, my members are going to continue growing for the higher-value products,” says Barry Cohen, the National Algae Association’s executive director. “We have algae companies that are growing on spec for different industries: the ingredients industry, the food industry, the nutraceutical industries. If their HP [Haematococcus pluvialis, a species of algae] meets spec, they have companies that will buy every drop that they can make.”

Astaxathin is a trendy antioxidant, and algae farmers have developed HP strains that yield it at levels of more than 4 percent by weight after the crop is dried out. Cohen says the supplement, which is touted as an anti-aging weapon and across-the-board health booster, can fetch more than $10,000 for a gallon. The omega-3 and omega-7 fatty acids found in fish and fish oil come from the algae in fish’s diets—so algae companies are cutting out the middlefish, extracting the compounds directly from their crops and marketing them as vegan alternatives. Proteins from spirulina and other farmed algae cells may be in your post-workout protein shake. Algae proteins are being fed to cattle and to farmed fish, which are making their ways onto our dinner plates.

It’s not clear quite how big the sector is. The association represents “50 to 75” companies, Cohen said, and it runs an “algaepreneur” business incubator. But it doesn’t represent the entire industry. The industry is disorganized and lacks political clout in Washington, where Congress has spent little time or money investigating the sector’s size or importance—or how it could be supported by the government. Most of the attention afforded to algae farming in the Capitol is given to biofuel efforts. In a nation obsessed with energy, algae’s higher-value products, the ones that are already commercially viable, tend to be mentioned as mere afterthoughts.

A Congressional Algae Caucus was formed last year, and it has met twice so far. Officials say it has discussed all of the potential uses of algae—not just the promise of biofuel. When founders Rep. Scott Peters, D-Calif., and Rep. Matt Salmon, R-Ariz., put out the call last year for colleagues to join the caucus, they noted that proteins and carbohydrates from algae “are being used today for food, animal feed, health products and supplements, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics.” Yet the introductory letter they sent to their colleagues focused largely on biofuels. It concluded by saying that the caucus would help officials learn about “green crude and its derivatives,” to “ensure that government does not discriminate against algae fuel as an alternative.”

This kind of energy-centric rhetoric around algae farming ignores realities that are widely acknowledged within the industry. “Our initial sales will be in the form of algae-derived oils for nutritional supplements,” said Paul Brunato of Aurora Algae, a Hayward, Calif.-based startup that just wrapped three years of trials at a test facility at the edge of the Western Australian town of Karratha. “Feed and food ingredients are part of our future product pipeline. We have produced biofuel from our algal oil, but at this time it’s just not economically feasible. The economy of scale just isn’t there.”

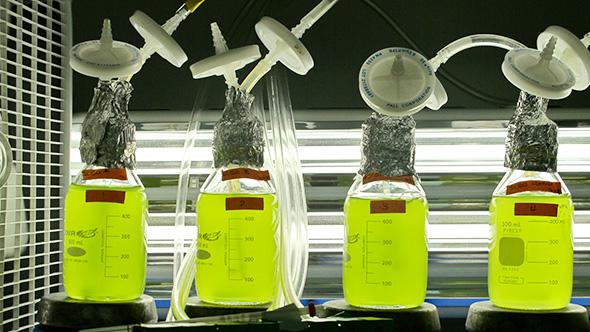

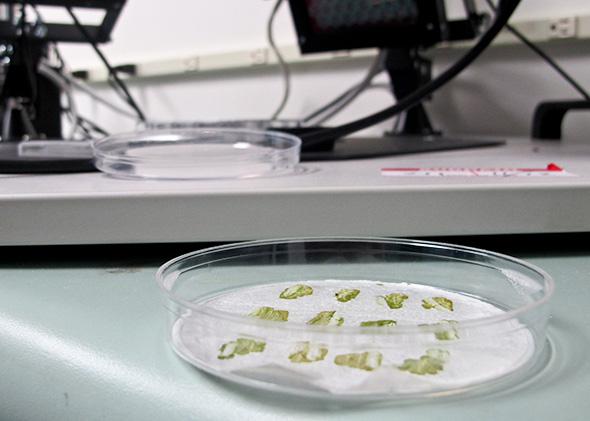

Photo by John Upton

The startup employs a team of 36 scientists and even more engineers than that. They have spent seven years breeding strains of Nannochloropsis, a common variety of saltwater algae, and fiddling with growing and cultivation methods to improve yields. Their experiments in the Australian Outback involved changing water-circulating methods and nutrient and oxygen levels to yield crops that sometimes doubled their weight in a single day, a rate of growth that can sometimes be found in the wild. The test facility was producing 15 tons a month of dried algae from six 1-acre ponds when experiments concluded in December. The company says those strains could start to be produced on a prodigious commercial scale within a couple of years—it’s just trying to figure out where in the world is the best place to do that.

The company has studied potential build-out sites in Australia, Mexico, Italy, India, and Florida, searching for the ideal combinations of sunlight, government support, access to saltwater, and year-round warm temperatures. Too much heat kills algae; too much cold causes it to grow slowly. The most promising sites so far appear to be in Australia and at an old shrimp farm near Harlingen, Texas. Aurora announced in early April that it would build four 1-acre ponds on the sprawling Texan property. If that goes well, the farm could be expanded in phases up to hundreds of acres—all to help meet humanity’s demand for food and health.

There’s something darkly romantic about using our own bodies as storage vessels for carbon dioxide produced by power plants and captured using algae. It’s time for the fading euphoria surrounding climate-change-fighting algae cultivation to shift away from energy to where it truly belongs: in our food.