“My friends in Syria, they used to call me Abu Abdou,” says Zeina Al-Shamaly with a grin. “It means ‘tough guy,’ someone who is not afraid of anything.”

It was March when I first met Al-Shamaly, 32, as she sat cross-legged on a damp, matted blanket that had been donated by UNHCR, the U.N. refugee agency. Beneath the cheap gray fabric of her U.N.-issued tent was a synthetic swelter, as the spring temperatures steadily rose. Al-Shamaly’s tent was pitched in one corner of a small, grubby courtyard, a space she shared with more than 50 families. At the port of Piraeus in Athens, scores of other tents dotted the horizon.

Back then, some 27,592 refugees—mostly from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Al-Shamaly’s home country of Syria—were stranded in mainland Greece. Today, that number has risen to more than 40,000.

For more than seven months, thousands of refugees—like Al-Shamaly—have been stuck in political limbo in Greece, living in deteriorating conditions, uncertain if they will be given asylum in Europe or deported back to Turkey. Al-Shamaly is one of many. And she knows it. As her Facebook profile put it: “Don’t worry. I’m just another Syrian.” But she is also unusual, because she is a single, childless woman, negotiating the refugee process alone.

* * *

The deal between Turkey and the European Union, ratified on March 18, was intended to control the flow of refugees into Europe. Under its terms, at least some of the thousands arriving in Greece, mostly Syrians, would be relocated to EU countries. All new illegal arrivals to the Greek islands would be detained, and the majority would be marked for deportation back to Turkey.

Harriet Dedman

The agreement was met with international furor from the aid community and fiercely criticized by nongovernmental organizations that work with refugees, including the UNHCR and Doctors Without Borders. “Europe’s attempts to outsource migration control is having a domino effect, with closed borders stretching all the way back to Syria. People increasingly have nowhere to turn,” said Jérôme Oberreit, international secretary-general of Doctors Without Borders. Amid such rancor, the deal’s implementation stalled, further compounded by the political distractions of the successful Brexit referendum in Britain and the aftermath of July’s failed Turkish coup.

“It is a well-known fact that the system is overloaded,” Sophia Glazunova, a protection officer for the UNHCR, confirmed, as busloads of refugees waited in long, silent lines at her registration and processing center near Thessaloniki, Greece, this summer.

* * *

At 10:30 a.m. on March 3, Al-Shamaly arrived on the Greek island of Lesbos after two and a half hours at sea. Over the course of 2015 and 2016, more than 1 million refugees crossed the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece.

In the days following her arrival, the border between Greece and the Republic of Macedonia in the former Yugoslavia—the land route into northern Europe—was closed. By the time Al-Shamaly arrived in Athens, on the overnight ferry from Lesbos, the deal between the EU and Turkey had been signed. Al-Shamaly had managed to escape the islands—where deportation and detention had become a panicked reality for those still there, but with the routes into northern Europe now closed, Al-Shamaly was stranded.

Al-Shamaly is from Al-Salamiyah, a city in western Syria, about 30 miles from Homs. Before the civil war broke out, it was home to about 65,000 people. The city holds a location of strategic importance in the ongoing conflict, between the city of Hama and the northern road to Aleppo, Syria’s largest city. ISIS, al-Qaida factions, and President Bashar Al-Assad’s forces continue to contest its occupation. Al-Shamaly’s mother is still in Al-Salamiyah.

Al-Shamaly’s journey began in 2014, when she fled Syria for Turkey. En route, she was arrested by the Syrian police for breaking curfew and was incarcerated for 48 hours, during which time she was physically assaulted by the guards. “They smashed a rifle into my face,” she says, calmly scrolling through iPhone photographs that show deep purple bruising. Once released, Al-Shamaly escaped over the Turkish border.

She stayed in Turkey for almost two years, working as a waitress in Istanbul for many months. “I was treated as little more than a slave,” she says. Human Rights Watch has recently highlighted the exploitation of Syrian refugees working inside Turkey. Before January, refugees were denied work permits, and even now that some refugees have permission to work, that right does not mean they are properly compensated. Refugees may receive as little as $300 a month, well below Turkey’s gross monthly minimum wage of $560. “Refugees are treated like second-class citizens [in Turkey],” Al-Shamaly says. “I never want to work as a waitress again.”

Last year, Al-Shamaly’s 28-year-old sister, Leila, decided to travel to Germany with her husband and daughter. Her brother, 26, followed shortly after. Their decision was made in fall 2015, when hundreds of refugees drowned in the Aegean Sea. Al-Shamaly was too scared of the sea to leave with them. They reached Germany in December. By January, with rumors circulating that European nations were closing their borders to refugees, Al-Shamaly decided to face the journey alone.

With a degree in English literature and experience as a teacher in Syria, Al-Shamaly speaks English with ease. A well-thumbed copy of Virginia Woolf’s Night and Day, a novel that tracks two European women living contrasting lives, is tucked into her small bag of belongings. Al-Shamaly grins wryly, “It seemed to be appropriate. Night and day. My life has changed so much.”

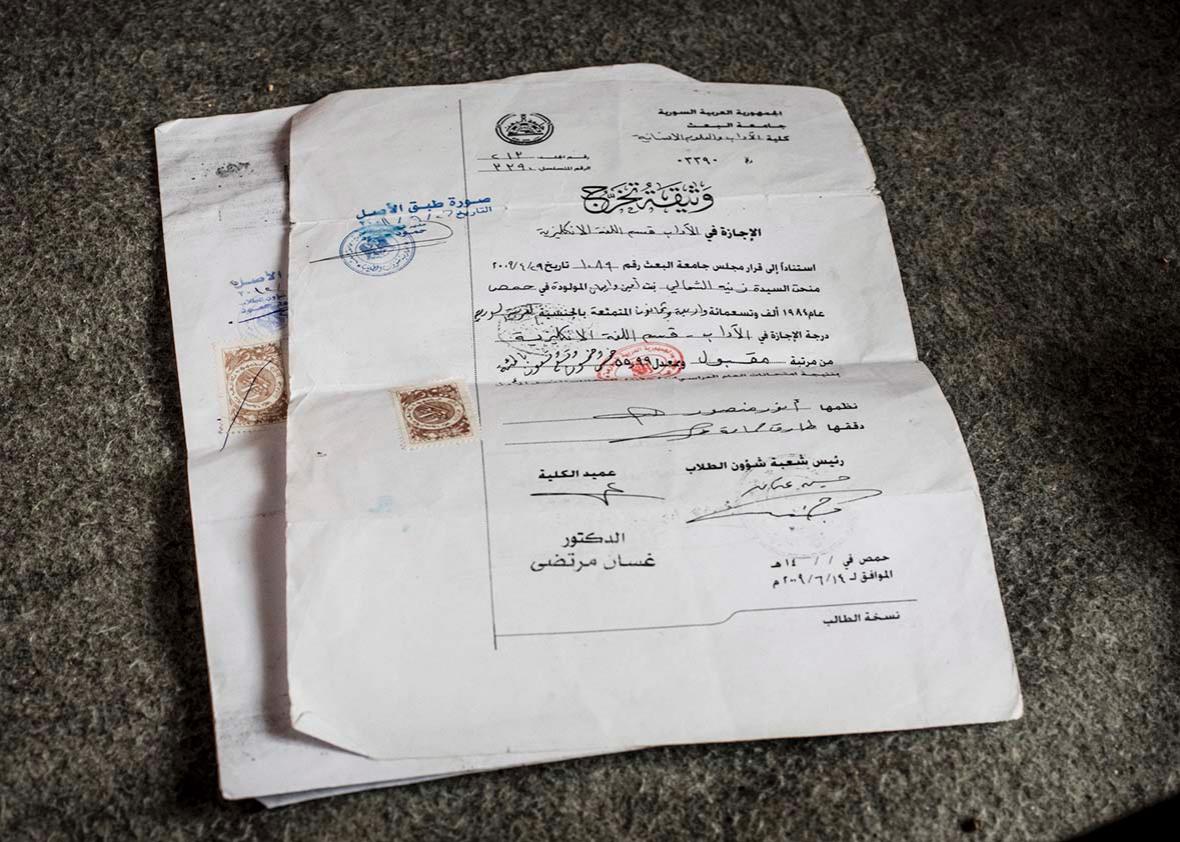

Inside her tent, a closely guarded yellowed envelope holds a few carefully preserved documents. Al-Shamaly opens them with caution and precision: her university degree, her certificate in informatics, issued by the Syrian Computer Society, which proudly sets out her capabilities in computing—the results of a test taken in Hama in 2014, at the height of the civil war.

A stern-looking Al-Shamaly stares out of an old Syrian ID card. “I was so fat then!” she grins. “I hate looking at that photograph. These days I have no appetite.” She runs her finger over a green-inked poem, written on an old diary page from a Saturday in 2011.

Thanks in part to her strong English-language skills, Al-Shamaly made many friends among the volunteer communities in Greece. Once she arrived in Europe, she began to volunteer in the refugee camps on the island of Lesbos and later in Athens. She is proud of her yellow vest, which designated her as a volunteer. She worked as an Arabic-to-English translator and helped distribute aid and supplies to her compatriots.

“I just had to do something. I had to help these people, and I had to have purpose—to my own days and my own life. I’m going crazy here,” she says. “But, as long as I can have a shower, that at least makes life better.” Unfortunately, showers were hard to come by.

As a woman traveling alone, Al-Shamaly remains fiercely independent. She seems to actively shut out the risks that she faces, the frequent catcalls from men in the camps. Some nights she asked her friend Ali, a young man, to sleep in her tent, so that she will feel safer and to discourage any opportunistic intruders.

In a recent, damning report, the Women’s Refugee Commission—an independent think tank focusing on problems that affect displaced women—called for a dramatic boost to financial, material, and human resources to specifically safeguard female asylum-seekers trapped in Greece and to remedy “a policy of delay, discrimination and despair.” According to the WRC report, more than 50 percent of the refugees stranded in Greece are women, and they face unprecedented threats to their physical and mental well-being.

Al-Shamaly’s ease with the volunteers and local Greeks does not go unnoticed, attracting the ire—and accusations—of her neighbors. “They can call me a slut, “ she says. “I’m too tired to care. I’m a tough guy, remember.” Her rattled demeanour suggests otherwise.

According to the WRC, since the EU-Turkey deal was struck in March, there has been an increase in reports of gender-based violence among refugees in Greece: “[G]aps in security expose women and girls to numerous threats, including [gender-based violence], trafficking and even kidnapping of children.”

Harriet Dedman

The tent where Al-Shamaly sleeps on the ground, curled up in a donated sleeping bag, is pristine, ordered, and aired. There is no way to seal the flimsy and cheap tent at night.

“I don’t sleep very much,” she says.

On June 29, in a scheduled interview, Zeina spoke with the Greek Regional Asylum Office and Appeals Authority, the agency that oversees the relocation of refugees. Her interview was conducted over Skype. With a shortage of officers and personnel, even in Athens, and thousands of refugees to interview, Greek authorities used Skype to conduct the first round of questioning. The technology was disastrous for refugees with limited funds, lack of access to the internet, and no common language. The WRC’s report condemned the use of Skype for these interviews. (The method has since been retired; refugees are now screened in person.)

As a Syrian, Al-Shamaly stood a greater chance of being relocated to an EU member state, which would mean permanent papers to remain—indefinitely—in Europe, to work and build a home, an escape from the transient and squalid camp conditions in Greece. However, the chances of her being reunited with her family in Germany were always slim. She could be sent to any of the EU member states offering to host strict quotas of refugees. Only nuclear families, defined as parents and children, can be reunited under the deal between the EU and Turkey, so Al-Shamaly’s siblings didn’t meet the criteria. “It is better for [Al-Shamaly] to take her relocation, wherever it may be. She will then, at least, move somewhere,” said UNHCR’s Glazunova.

On Facebook, Al-Shamaly sends me updates on her meetings with officials. A recent update was curt: “Romania,” she wrote. “It looks like I’m moving to Romania.”

Romania will receive a total of 6,205 refugees over the next two years, according to its immigration office. “Romania will be her country of registration, her home, where she can work,” says Glazunova. “It may take up to five years for her residency papers to be finalized there.”

In the next few weeks, Al-Shamaly will arrive in the eastern Romanian city of Galati. There, she will face her new life, alone, some 800 miles from Germany.

“Now, I am afraid,” Al-Shamaly says. “I am afraid of not having a future.”