One way to make the trauma of being raped worse: Send the victim a hospital bill for the “rape kit,” or the exam used to collect forensic evidence after a sexual assault. According to writer Elyse Anders, this is exactly what happened to her. On Sunday, Anders tweeted, “My rape kit account is being sent to collections bc I refuse to pay for the investigation of a crime against me.” By early Tuesday, her protestation had been retweeted nearly 3,500 times.

Multiple people offered to cover the bill for her; collecting a rape kit usually costs $1,000 or more. Anders redirected them to donate to a nonprofit that works with survivors of assault. “I’m not paying it and I don’t want anyone to pay it. It shouldn’t be a bill sent to me or any victim,” she wrote. In response to Anders’ plaint, NorthShore University HealthSystem, the Chicago-area hospital chain to which she was in debt, tweeted an apology and a promise to “resolve” the issue.

When I contacted NorthShore, a spokesperson told me that the health system does not charge patients for rape kits, and that Anders had received “a minimum charge for physician services.” Anders didn’t respond to my request for an interview. But whatever the size of the bill that was sent to her, it’s in no way unusual for a rape survivor to be asked to pay for her own rape kit. When CBS reported on the issue last year, they found cases of survivors being billed in 13 different states. As one incredulous commenter pointed out this week, “If your house is burgled it doesn’t cost you $1200 to file a police report.” This just one more way that the justice system’s approach to sexual assault isn’t fair.

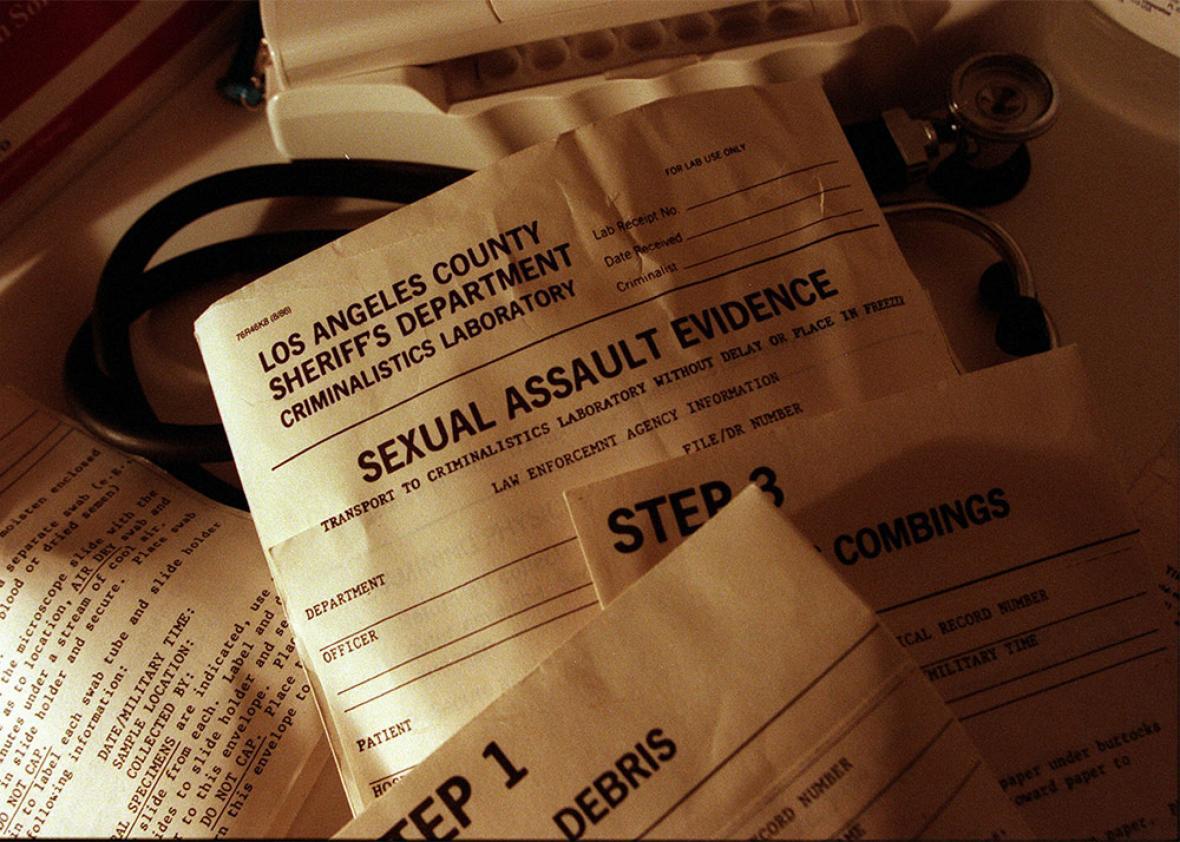

Rape kits are frequently in the news because of another endemic problem: the enormous backlog in testing them. In 2014, the Department of Justice calculated that there were about 400,000 untested rape kits collecting dust in evidence lockers across the country. Parts of the U.S. that have processed old rape kits have found it well worth their while: Detroit has almost finished clearing its backlog of more than 11,000 kits, and has found 2,616 suspects, 477 of them possible serial rapists, in the process. This fall, a partnership between the Justice Department and the New York County District Attorney’s Office set aside $79 million for the testing of rape kits across the country.

Why would survivors ever be asked to pay for the collection of this essential evidence? The federal Violence Against Women Act technically prohibits this, but, as a ProPublica and Huffington Post Investigative Fund collaboration has written, the law is vague on how state bureaucracies should step up to cover the bills, and some states have left loopholes that victims get caught in. A 2014 Urban Institute report found that 34 states were drawing on general “victim compensation funds” (amassed from fines paid to the state) to cover rape survivors’ medical bills. But CBS found that in some states, including California, survivors only get help covering the exam if they’ve already reported the rape to the police—a policy that is in violation of VAWA. Other states, such as Ohio, will pay a set amount towards an exam, but will allow the hospital to balance-bill the victim. Still others—including Minnesota, Kansas, Arizona, South Dakota, and Nevada—leave it up to individual counties to cover the costs.

This patchwork system is slowly improving. In news reports about the billing of victims, Louisiana and Illinois (where Anders’ rape kit was apparently collected) are the most frequently cited offenders—and in 2015, both passed laws to make sure that survivors aren’t charged for rape kits.

Still, it remains common for survivors to receive a bill in the mail for other emergency health care related to a rape. The rules governing this vary even more widely than those around rape kits: Authors of a 2012 AEquitas report found that while, for example, 15 states will pay for a survivor’s STI testing, only five will pay to treat injuries related to an assault. To many survivors and advocates, this is just as bad as being charged for the rape kit. As Kellie Greene, who was raped in 1994 and subsequently founded the group Speak Out Against Rape, told CBS: “It’s like being punched in the gut when you open that mailbox and you see that bill.”