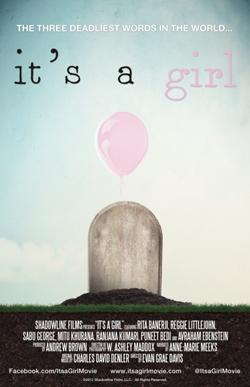

It’s a Girl, a documentary about the tragic practice of sex-selection abortions in India and China, is being widely screened by pro-choice groups across America, including the New Jersey Chapter of the National Organization for Women and feminist groups on university campuses. It was an official selection for the Amnesty International Film Festival in 2012 and appeared in Ms. magazine’s feminist movies review. But as organizations and groups evaluate whether to screen this movie, they should be aware that the film’s director worked for Harvest Media Ministry, an organization that makes pro-life and other videos for church groups.

How did this happen? How did a movie linked to a pro-life group become the darling of the pro-choice community? The story involves clever disguises on the part of financing sources that managed to hide their involvement and pass off a movie about the horrors of sex-selection abortions as just a sympathetic movie about the plight of women in India and China. And the pro-life message is subtle enough that they got away with it.

Shot on location in India and China, the film starts with a poor rural woman from India smiling while she tells the audience that she killed eight of her female babies. The film describes a culture of violence against girls and women in India from being killed in wombs, to killed as infants, to starved and trafficked as young girls, to being beaten as wives. That part is true. Still, when I watched the film, I was reminded of the seminal article by now-dean of SUNY Buffalo Law School, Makau W. Mutua, in which he coined the grand metaphor of human rights discourse as one where the actors are “savages, victims, or saviors.” In this case, Indians are savages, the women are victims, and the Americans are the saviors.

The closest the movie comes to endorsing a broad anti-abortion message is at the end, when Indian writer Rita Banerji states that “all life is sacred.” The final scene is a lengthy heart-wrenching depiction of a woman playing with her two daughters who she refused to abort despite her in-laws’ insistence. But the message is subtle enough that a recent review appearing in the Atlantic claims that the movie “doesn’t buttress either pro-life or pro-choice—or, at least, doesn’t buttress one at the expense of another.”

I was recently asked by a human rights student group to lead a discussion of the film, but after a little research I became suspicious. The film was not cheap to make yet acknowledges no funding sources. It is also made by a director who does not specifically mention any prior experience or background in India or China and whose official biography does not mention any prior works. I finally searched the owners of the domain name associated with the film’s official production company. The domain name of Shadowline Films is registered to Evan Davis of Tucson, Ariz., (the same name as the filmmaker except without the middle name).

Only after searching for “Evan Davis Tucson Arizona” was I able to discover that Davis is also the media director of Harvest Media Ministry, and the domain name of that company is also registered to Evan Davis of Tucson. The website of Harvest Media Ministry states that its mission is to provide “well produced, strategic communication tools and support services that serve and encourage ministries, Mission organizations and the Church.” Further, Harvest Media claims its purpose is to “keep God and what He is accomplishing around the world as the central message of each media tool [they] develop.” Among its portfolio of works, the website features a video describing “unborn children” as “46 million people who will be killed this year.”

Evan Davis, the media director for Harvest Media Ministry, and Evan Grae Davis, the director of It’s a Girl, have segregated personas on the Internet. On the website of Harvest Media, Evan Davis’ biography proclaims that his “passion is to equip those who are called to bring the hope and light of Jesus Christ to the world through the provision of strategic media communication tools and storytelling methods.” Yet on his Facebook page that is associated with the film, under his religious views, he states that “it’s against my relationship to have a religion.” When I interviewed him, he elaborated on this point. “My relationship with God is a personal thing,” he said. “I don’t identify myself with a denominational group. But I believe in God. My faith is a factor in what motivates me in wanting to help people around the world and never tried to hide that.”Yet the film’s press kit does not mention his affiliation with Harvest Media Ministry and describes him as a “social justice advocate” who writes videos and directs educational documentaries “championing the causes of the poor and exploited.”

Why go to such efforts to hide the fact that Evan Davis aka Evan Grae Davis has also worked for a company that creates videos on behalf of faith-based groups to promote their interpretations of the teachings of Jesus Christ? When I asked Davis about this, he said that there was no ulterior motive in his failure to disclose his affiliation with Harvest Media Ministry and said he no longer works for the organization even though his biography is still on their website. However, when I told him that I discovered that Shadowline Films and Harvest Media Ministry share the same address, he said that they share “facilities and equipment,” and that some of the funding sources for the movie are the ones he met through his work with Harvest Media.

The film’s official website encourages people to “[h]elp keep a girl in India alive by donating to the Invisible Girl Project, whose programs encourage Indian mothers to keep their girl children alive.” However, there is no link to the website of the Invisible Girl Project from the Web page on which the donation is solicited (but only from the “partner organizations” page). Only after searching for the charity’s website did I find that the charity states that it “follows pregnant village women [in India] who may be susceptible to committing feticide or infanticide.” The website further states that if their “partner finds that a baby girl’s life has been taken, [the] partner pursues justice for the baby girl in the local court system.”

Pro-life groups have in recent years begun using the practice of sex-selective abortion—a practice that is rare in the United States—in foreign countries as an excuse for limiting women’s access to abortion here at home. A bill was recently filed in the North Carolina legislature to ban sex-selective abortion, and a similar bill was defeated in the U.S. House of Representatives last year. Although no one supports sex-selective abortion, pro-choice groups correctly worry that such laws could be misused to restrict abortion more broadly.

Regardless of what Davis’ goal is in making the movie, it is clear that efforts have been made to hide any affiliation with Harvest Media Ministry. In fact, Women’s Rights Without Frontiers, a partner organization for which the film’s official website seeks donations, and whose founder features prominently in the film is also part of a coalition that seeks to ban sex-selection abortion in the United States. Whether or not the intent of the movie is to push states to adopt sex-selection abortions bans, pro-life groups seem to be using it for that. And he refused to disclose to me the exact sources of funding for the film. Then the question becomes: What is the point of the movie—at least in terms of solving the problem in India and China?

Indian women’s groups have long been working on preventing feticide and violence against women. In India, it is illegal for doctors to inform women of the sex of the fetus and to perform sex-selection abortions, yet the practice not only continues but has increased, because (in part) ultrasound machines (supplied by American companies) are more widely and cheaply available. These ultrasound machines are used illegally to detect and inform parents about the sex of the fetus. Parents who want to have a boy will abort the female fetus once they know the sex. Some suggest that the low price and widespread availability of this technology may actually have reduced the rate of infanticide, though the movie does not mention this.

Female feticide and infanticide will end only when the inequalities— such as dowry, inheritance laws, lack of equality in education, lack of economic opportunities, and other forms of discrimination against girls and women—that create a son preference change. As well-intentioned Americans who wish to address human rights violations in other countries, we should fully inform ourselves about the background, goals, and tactics used by filmmakers and organizations before we choose to support them.