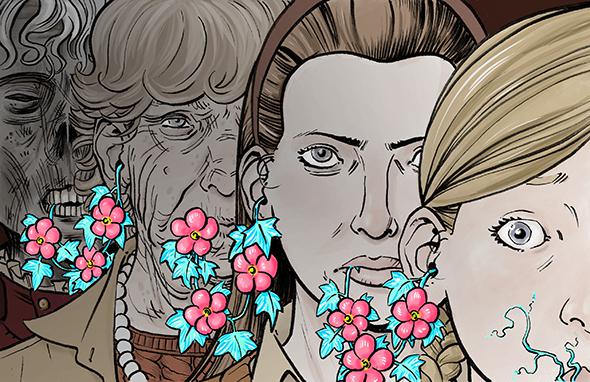

Ask any V.C. Andrews fan about the 1987 film adaptation of Flowers in the Attic and she’ll probably tell you that it’s all wrong. The film soft-pedaled the novel’s incest, altered the ending, and screwed up most of the details (it was arsenic-laced doughnuts, not sugar cookies). They didn’t even include the tar incident. What a relief that the upcoming Lifetime TV movie adaptation promises to be faithful to all the dark and sordid details of the novel. After all, many of us have been waiting three decades to climb up the stairs to the attic with Cathy again.

Flowers in the Attic, a novel about four children who are locked up and mistreated in their rich grandparents’ mansion while their conniving mother tries to win an inheritance, was published as adult fiction in 1979, and it was as adult fiction that it hit the New York Times best-seller list within weeks, despite the fact that nobody had ever heard of V.C. Andrews. But reading Flowers in the Attic quickly became a rite of passage for teenage girls in the 1980s. Copies of the book and its sequels were passed from girl to girl, as if we could peer through the novels’ foil-embossed keyhole covers to the powerful secrets within. For many of us, Flowers in the Attic was the start of a love affair with V. C. Andrews that lasted throughout our teens, until it was replaced, somewhere around our first college lit class, by a sense of mild embarrassment. Oh, it was a phase, we told ourselves.

And yet, as all the buzz about the Lifetime adaptation reveals, we are clearly not over Flowers in the Attic. For women of my generation, Cathy Dollanganger’s story continues to possess a weird, singular power. It’s also an elusive one, and most of us have a difficult time articulating why Cathy’s story embedded itself into our imaginations, and why we’re so excited to revisit it now.

So why was Flowers in the Attic so uniquely appealing to its first teenage readers? The novel is narrated by Cathy Dollanganger, who is imprisoned with her siblings at the age of 12 and finally escapes at the age of 15. It’s a harrowing tale of abuse and neglect that includes beatings, starvation, and poisoning. It’s also, notoriously, the story of an incestuous love affair between Cathy and her older brother that culminates in sexual assault. Sure, those shockingly novel themes attracted readers, but the emotional payoff for teens was much deeper than the thrill of reading something taboo. In large part, Flowers in the Attic drew its power because it gave voice to a visceral, adolescent feeling of being held hostage by your own family.

Cathy is restricted by her mother, disapproved of by her mother, and ultimately abandoned by her mother. Any teenage girl could relate; even if we didn’t share the abuses she suffered, we felt all of her adolescent feelings of victimization, hopelessness and resentment—especially at our own mothers. Cathy’s experience vindicated our own feelings of how unfair our treatment was by our families, and the litany of horrors she suffers fueled a powerful sense of righteous anger.

Flowers in the Attic contained the emotional stuff of adolescence that was missing from the YA novels that proliferated in the 1970s and ‘80s. Even Judy Blume, queen of important YA topics, wouldn’t get close to this dark, messy territory. Like Blume’s Forever…—the other novel girls passed around in the 1980s, due to its semi-titillating-and-very-informative content about safe sex—the books we were supposed to be reading to help us cope with our various adolescent challenges delivered many reassurances that things would eventually be OK. By contrast, Flowers in the Attic indulged our fear that things were so deeply fucked up that they might never be OK. Near the end of Flowers in the Attic, Cathy even comments on how inadequate media is for addressing her emotional life:

Chris and I had educated ourselves from reading so many books, and television had taught us much about violence, about greed, about imagination, but it had taught us hardly anything that was practical and useful in preparing us to face reality.

Survival. That’s what TV should teach innocent children. How to live in a world that really doesn’t give a damn about anyone but their own—and sometimes, not even their own.

The novel addressed the disconnect between feelings that were hard for us to acknowledge and fiction that we were supposed to like. Despite its excesses, it conveyed a sadness about being robbed of normalcy that felt authentic to teens that were experiencing varying degrees of their own family dysfunction. In that way, Flowers in the Attic was a uniquely comforting story.

But V.C. Andrews’ ability to give voice to the chaotic anger of our teen lives isn’t the only reason why Flowers in the Attic resonates with us still. The novel and its sequels also recognized a deep and abiding fear that has shaped women of my generation: the fear of turning into our mothers. As Cathy’s love and adoration of her mother, Corrine, turns into bitterness and anger in Flowers in the Attic, she becomes determined to get free of her family and be nothing like her mother. Yet through the decades that span the novels that follow, Cathy finds herself becoming more and more like Corrine. Petals on the Wind (1980) is driven by Cathy’s desire for revenge, which compels her to look and behave like Corrine in order to seduce her husband. By the end of that novel, Cathy has also begin to duplicate her mother’s choices: She begins an incestuous family with her brother, lies to her children about his identity, and finds herself installing children’s beds in her own attic. The final words of Petals on the Wind are Cathy’s ominous monologue: “But … I am not like her! I may look like her, but inside I am honorable! I am stronger, more determined. The best in me will win out in the end. I know it will. It has to sometimes … doesn’t it?”

If There Be Thorns (1981) ratchets up the filial conflict, as Corrine moves next door to Cathy’s family and poses as a mysterious dowager so that she can spend time with Cathy’s sons. Cathy, now in her 30s and grappling with the reality of parenting, begins to soften in her judgment of her mother. She tells her son Jory, “When I was ten, I used to think that adults had it so easy, with all the power and rights to do as they wanted. I never guessed being a parent was so difficult.” Eventually, Cathy and Corrine find themselves locked together in a cellar. The ensuing fight starts a fire that threatens to kill them both. Corrine sacrifices herself to save her daughter, enabling Cathy to finally, posthumously, forgive her mother.

The plotlines may be outlandish, but the patterns of Cathy’s relationship with her mother are oh-so-familiar. Cathy wants to be different from Corrine but feels terrified that she can’t stop herself from turning into her; that tension is at the heart of all the Dollanganger novels. The series isn’t so much about disrupting destructive family patterns as it is about expressing their horrible inevitability. By locking them up together, Cathy’s mother all but guarantees that Cathy and Chris will end up creating an incestuous, dysfunctional family just like hers. Even their family name, Dollanganger, suggests that Cathy and her siblings are never more than just doubles of their parents. And Seeds of Yesterday (1984) seals the deal when Cathy dies in the attic of a mansion built to be just like the one in which she was imprisoned as a teen.

V. C. Andrews’s preoccupation with escape, confinement, and difficult moms was likely motivated by her own personal experience. Due to an injury suffered in her teens, Andrews used wheelchairs and crutches throughout her life, and lived a solitary existence with her mother as companion and caregiver. (Andrews died before the prequel Garden of Shadows was published in 1987, and though there’s much debate on the topic, it’s most likely all other V.C. Andrews novels besides the Dollanganger series, two novels in the Casteel series, and My Sweet Audrina were written in full or in part by others.) It’s not hard to imagine the feeling of permanent imprisonment Andrews may have felt. After all, she did dedicate Flowers in the Attic to her mother.

But these are obsessions we all have, too, and so we devoured the books and suffered the disappointment of that first film adaptation. It’s no surprise that a new television adaptation of Flowers in the Attic is on the horizon. The girls who came of age with Flowers in the Attic are now in our 30s and 40s, and if the much buzzed about Dotty Bingo survey from earlier this year is to be believed, most of us have already turned into our mothers. (Some of my generation even have daughters of their own, and they worry that the helicopters they’re piloting may be as oppressive as the attics they once read about.)

Revisiting Flowers in the Attic is a bit like reading it alongside your teen self. You can replay all the emotions you had when you first read it, but you can’t really feel them anymore. It’s not nostalgia that draws us back to Flowers in the Attic and the Dollanganger novels. And it’s not because they’re fun, either. (The novels are neither as good as you thought they were, nor as a bad as you’d like to remember them.) Instead, it’s because V.C. Andrews continues to give voice to feelings that are hard for us to acknowledge. Like Cathy, we got out of our mother’s attics—but we never quite escaped them.

—

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.