Earlier today, the Brookings Institution released a report, “Is a Student Loan Crisis on the Horizon?” Its implicit answer: “Not really!” The report argues that much of the panic over student debt is the product of media hype. The typical borrowers are “no worse off now than they were a generation ago,” it concludes. As for those art history majors with $100,000 in loans we always hear about? Well, they’ve been around for a while: The “borrowers struggling with high debt loads frequently featured in media coverage may not be part of a new or growing phenomenon,” Brookings reported. It earned a glowing write-up from David Leonhardt at the New York Times, who tweeted out this catchy stat:

As you might expect, there were objections. Over at the Awl, Choire Sicha delivered an extended thrashing of the report, titled “That Big Study About How the Student Debt Nightmare Is in Your Head? It’s Garbage.”

It’s not garbage. At the same time, contra Brookings, student debt already is a crisis—but a poorly understood one. So here’s the big question: Are we overreacting to student debt or not?

Before we try to answer that question, let’s first unpack the two big takeaways from Brookings:

Point No. 1: Debt burdens have grown, but they’re smaller than you think.

Here are some stats you’ve probably heard before: More than 70 percent of four-year college graduates borrow for school, finishing with an average of $29,000 in debt. These are the kinds of straightforward numbers that are engineered to soar around Twitter with ease. The problem with them is that they mash together all sorts of students—graduates at Ivy League schools, graduates at expensive but unheralded private colleges with limited financial aid budgets, graduates from budget public campuses, and so on and so forth. They also focus on students straight out of school.

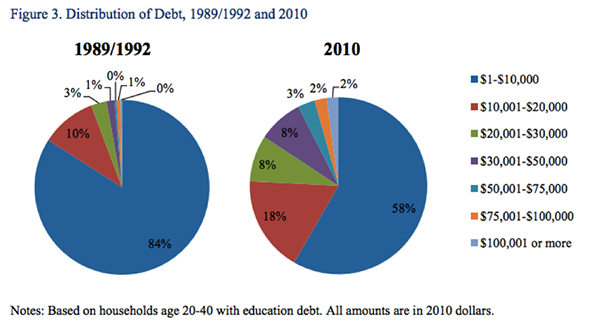

The Brookings study tries to take a slightly broader and more nuanced view. Using the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, it looks at households headed by Americans between the ages of 20 and 40. Of those individuals with education debt, it concludes, 58 percent owe less than $10,000. And yes, only 7 percent owe more than $50,000. It’s worse than 20 years ago, but six-figure loan balances are still a rarity.

Courtesy of the Brookings Institution

In his critique, Sicha essentially argues that we shouldn’t trust the data Brookings draws from. He has some decent points. Because the Fed reports on households, it doesn’t actually have information on individuals. To deal with this, the Brookings team just takes each household’s total debt load and divides it by the number of people living together. So if a couple owed $40,000 to the Department of Education, they’d each get marked down as owing $20,000. That’s not exactly precise, but it’s not crazy.

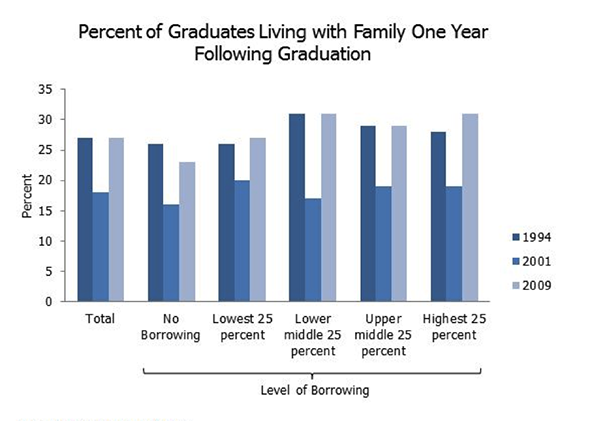

More glaringly, the report excludes borrowers who can’t support themselves financially and live at home with their parents, since their households are probably headed by people older than 40. (Just to complicate things, if that borrower is financially independent but still living in mom and dad’s basement for some reason, then the Fed counts him as his own independent household.)

I asked one of the study’s co-authors, Matthew Chingos, about this. He said he and his partner, Beth Akers, weren’t worried that leaving out boomerang kids would affect their results, because roughly the same percentage of college graduates live at home one year after school today as they did in the early 1990s. Moreover, they’re evenly distributed across the borrowing spectrum. By their logic, the live-at-home grads shouldn’t affect the long-term trends or skew the data in any particular direction.

Courtesy of the National Center for Education Statistics via the Brookings Institution

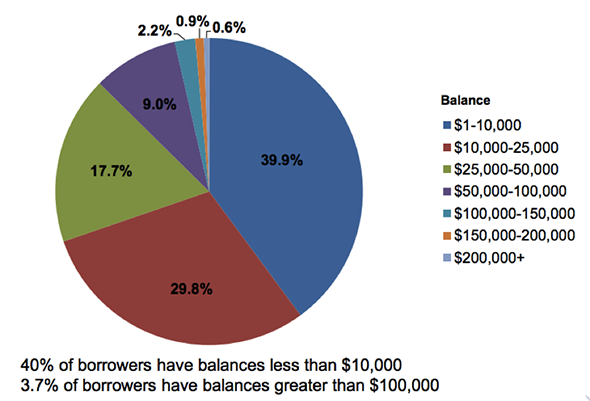

I don’t know if I buy their point entirely. More than one-fifth of all college graduates younger than 35 now live at home, and the financial situations of older boomerangers might differ systematically from kids who leave the nest within a year or two of getting their degrees. But there’s a bigger point to be made: The Brookings findings here aren’t wildly different from what we already know about student loan debt. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which does look at individual credit reports, finds that only about 12 percent of all student loan borrowers—including those older than 40, who are responsible for about one-third of the total debt—owed more than $50,000 at the end of 2012. Since younger borrowers tend to have lower average balances, there’s no reason to think that their pie charts look much more terrifying than the one below.

Courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York

So maybe no more than 7 percent of young student debtors owe more than $50,000. Maybe it’s no more than 12 percent. In the end, the point is that they’re still far more rare than media portrayals make them out to be.

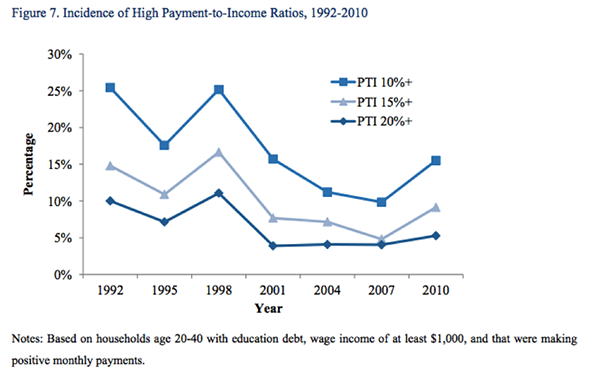

Point No. 2: Paying off student loans is no harder than 20 years ago.

College debt has grown since the early 1990s, but so have wages for bachelor’s degree holders. And Brookings suggests that the two trends have balanced each other out somewhat: As the study demonstrates, debtors are less likely to spend 10 or 20 percent of their incomes on loan payments than they were in 1998.

Courtesy of the Brookings Institution

The problem with these numbers isn’t necessarily that they’re wrong. It’s that they need to be read with lots of context. First, the paper itself notes that a major reason monthly debt burdens have shrunk is that the government began offering plans that allow borrowers to pay back their loans in smaller installments over longer periods of time. In other words, they’ve stretched out the process to make it less painful. That’s great from a policy perspective, but it doesn’t change the fact that graduates are taking on more debt today relative to their incomes than a couple decades ago.

Second, as Sicha notes, these figures only include households with at least $1,000 in wages and who are paying back their student loans. So they essentially exclude the unemployed, as well as the millions of borrowers who are in default, deferment, or forbearance. This does indeed seem like a huge oversight.

In short, what Brookings is telling us is that the students who aren’t having trouble with their loans aren’t having trouble with their loans. When I brought this up with Chingos, he countered that in every year they studied, from 1989 to 2010, roughly one-third of borrowers weren’t paying back their loans, meaning the long-term trend hasn’t changed.

But here’s the problem with that reasoning: The percentage of troubled borrowers might not have moved much—but there are many, many more of them. In 1989, 16 percent of young households had any student debt. By 2010, that number had more than doubled to 37 percent. If the same proportion are floundering, that means millions of additional individuals are in financial jeopardy.

All right, so back to the main question: Are we overreacting to student debt or not?

Let’s get meta for a second. There are two kinds of conversations that tend to dominate the topic of student debt: One is popular on Facebook, the other with policy wonks. The Facebook version is all about student loans as the scourge of a generation. The main characters are (largely) white liberal arts graduates who took on too many loans then had no idea what to do with their degrees when they graduated. It’s the story of that art history grad with $50,000 or more in debt serving you a cappuccino.

Those young people are real but relatively rare. Their problems do speak to some of the screwed-up facets of American institutions of higher education, which manage to charge outrageous tuition by preying on the status anxiety of upper-middle-class 18-year-olds and their parents.

But if you talk to people who study education policy for a living, they’ll tell you that the real victims of student debt aren’t English grads who took out a bit too much money to attend the University of Michigan or Oberlin. Those kinds of borrowers usually end up just fine. However, there is a huge contingent of working-class and minority students—some of whom are among the first of their families to attend college—who are getting chewed up by student debt. These are young people, and increasingly older adults, who might not have gone to college 20 or 30 years ago, but do now because the economy is brutal for job-seekers without a degree. They borrow for school, often to pay the inflated tuition at an unscrupulous for-profit institution or little-known vocational school, then frequently drop out. Suddenly, they find themselves in debt, with no degree and no guidance on how to manage their loans. They’re the reason almost 15 percent of borrowers default on their student loans after three years, and if anything, the media has underreacted to their plights.

I don’t think Sicha is trying to defend the Facebook-friendly version of the student loan crisis. He’s just taking justifiable umbrage at the idea that someone would try to minimize the problem, and he’s raising some justifiable questions about the data. But for its flaws, the Brookings study basically seems to have its heart in the right place: It’s designed to move our focus onto the troubled borrowers we don’t hear about. Its broad point is that there’s a very large group of student debtors who are faring just fine, and we don’t need to give them an extra hand through mechanisms such as refinancing or mass student loan forgiveness. Instead, we need to help out those “who make bad or unlucky bets,” as the report puts it. In other words, we should be very worried about those marginal, working-class students who get dropped into financial purgatory for the sin of trying to get an education. The art history majors? Not so much.