A few weeks ago, I chaperoned my son’s preschool field trip to the Maryland Science Center. As we entered the lobby, the kids were drawn to the artificial geyser, which shoots fountains of hot water into the air. But I focused on the donor plaques that festooned the lobby and the many signs pointing to the museum’s corporate benefactors: the Lockheed Martin gallery, the Legg Mason Pavilion. Even the information desk has a corporate sponsor.

Go to virtually any museum—and many hospitals, universities, and civic centers—these days, and you will find a prominent example of corporate philanthropy. If you were to judge it simply by the weight of public branding, you would think that the corporate community in the United States has stepped up to support charities in a significant way.

They haven’t. Over the past 30 years, corporate contributions to charities in the U.S., as measured by percentage of pretax profits, have fallen precipitously, from a high of 2.1 percent at its peak in 1986 to just around 0.8 percent in 2012. There is some year-to-year variability to this measure, because ironically enough, contribution percentages tend to rise in periods of poor corporate earnings. But the long-term curve is consistently down. Over the past 10 years, even through the ups and downs of a violent economic cycle, contributions as measured by percentage of pretax earnings have dropped by half. Given the scale of American business, it is surprising how small a role corporations play in charitable giving in the U.S., now comprising only about 6 percent of private-sector donations and only a little more than 1 percent of the $1.5 trillion charitable economy.

Let’s be clear. Corporate donations have increased substantially over time, from $3.67 billion 30 years ago to more than $18 billion in 2012. That’s a rise that exceeds inflation by approximately 115 percent. Proponents of corporate giving such as the Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy (CECP)—a very good advocate for corporate giving founded by the late Paul Newman—take reasonable pride in that growth. But those same observers tend to ignore the fact that giving as a percentage of profits—the best measure of relative generosity—has fallen far down. By comparison, the comparable measure of the generosity of individuals, as told by the percentage of disposable personal income, has remained solid over that time, changing from 2 percent in 1982 to 1.9 percent today—and barely deviating from that tight range in every year in between. For society as a whole, giving as a percentage of GDP has remained essentially unchanged. Only corporate contributions have fluctuated substantially and negatively over this time.

Some people will chalk this up to simple corporate fecklessness. But it is still surprising. In the age of instant communications and close public scrutiny of corporations, many companies have placed—at least rhetorically—an emphasis on contributing to society, both through community commitments to charity and by making their business practices more socially responsible. As Paul Polman, the CEO of Unilever, told Green Futures magazine in 2012, “CEOs don’t just get judged by how well their share prices are doing, but by what impact they are having on society.” In this context, the explanation of this decline in giving is hard to identify. In my conversations with experts on this subject, they expressed surprise, rejected it as a valid indicia of corporate giving (on the theory that quality of giving outweighs quantity of giving), had little plausible explanation for the trend, or some combination of the three. But even if there is no definite explanation for this trend, let’s look at three factors affecting corporate giving.

First, not everyone thinks that corporations should be giving lots of (or even any) money to charities or community organizations. In a 1970 New York Times article, the Chicago economist Milton Friedman famously wrote, “There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.” Friedman argued that corporate social responsibility was a simple taking, without authorization or business purpose, of the money of the company, shareholders, and customers. To him, it bordered on fraud. When presented with the notion that community support could be viewed as a business imperative, Friedman dismissed it as “hypocritical window dressing.” Friedman was hardly alone in this view. FDR originally opposed legislation permitting charitable contributions to be deducted as business expenses, on grounds essentially identical to Friedman’s argument. Only a vigorous lobbying campaign by big business overcame Roosevelt’s objections. It has become less popular over the years to make these arguments—though Steve Jobs–era Apple, for example, was notorious for its almost total abstinence from philanthropy. But there’s no doubt that silent support for these views within many companies operates as an effective brake on corporate giving.

Second, the decline in corporate donations is roughly coincident with an extraordinary rise in executive pay. Not only did CEO pay skyrocket fourfold in the 1980s, but the mix of compensation changed as well. At the behest of shareholder advocates, more and more executive compensation came loaded as options and other stock-related incentives. In effect, corporate executives increasingly had huge sums of money at stake tied to stock prices. During 2001–03, for instance, the aggregate compensation paid to top-five executives of public firms amounted to $92 billion, an almost unfathomable 10.3 percent of the aggregate corporate earnings of these firms—and at least 70 percent of that compensation was tethered to share price. Much of that payment was calculated based upon short-term measures. As Curt Weeden, a leading expert on corporate philanthropy, told me, if companies are focusing on short-term results, “social investments are likely to take a hit.” There is no definitive research on this point, but it is fair to theorize that, with executives so keenly focused on share price and compensation metrics, they have left less time to focus on social and community investments.

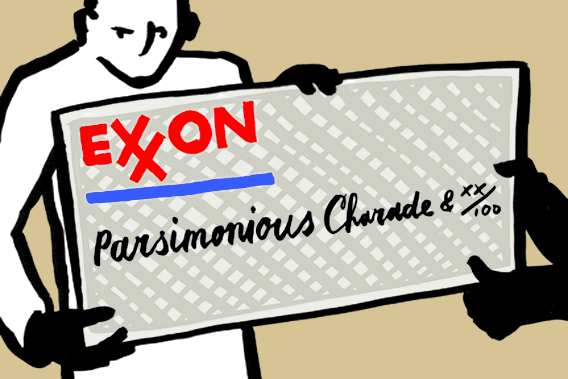

Third, the largest companies in America set the tone for the corporate community. By dint of size if nothing else, Exxon Mobil, IBM, and Chevron are benchmarks for corporate America.* But the tone that the largest companies set is not one of generosity. In each of the eight years that the CECP has closely studied donations, the largest companies have given less than the average, and not by small amounts. On average over this time, the Fortune 100 companies have given, on a dollar-for-dollar basis, some 40 percent less than the average—a pattern that closely parallels the relative parsimony of high-income individuals.

Again, it’s not that the largest companies don’t put in the most money in absolute terms. Exxon Mobil, for instance, was one of the top-five corporate donors in 2012, with cash contributions of $213 million. But with worldwide profits of almost $45 billion, Exxon Mobil would have to double its giving just to be average, percentage-wise. For all three companies, not only is their percentage of giving low by broader corporate standards, it is also declining: Each company contributed less in 2012 as a percentage of profits than it did 10 years before.

There are, of course, companies that give a significant percentage of profit to charities. In 2010, Kroger, the Cincinnati-based supermarket chain, gave away $64 million, or 10.9 percent of its pretax profit. Macy’s in that same year gave away 8.1 percent of profits. Some of the biggest consumer brands give away large sums as well: In 2012, Target contributed 4.7 percent of its profit and paired that sum with a commitment to donate $1 billion to public education. Also in 2012, Wal-Mart became the first company to give away more than $1 billion in a year, donating $311 million in cash and $755 million in product, amounting to 4.5 percent of its profits.

It is true, as the CECP points out, that numbers are not the sole measure of the meaningfulness of corporate contributions. Making philanthropy effective is terribly difficult work, and no doubt some companies—maybe even some of the ones that seem stingy—do it better than others. But in the corporate world, as elsewhere, nothing speaks louder than dollars. Most Americans now reasonably expect the companies they do business with to support their local communities in a meaningful way. In an age when corporations have acquired more and more basic rights of citizens—the right to own property, the right to sue and be sued, the right to be free of unreasonable search and seizures, the right to free speech, the right to engage in the political process—it is fair to look to them to accept more of the basic responsibilities of citizenship as well.

Correction, Aug. 8, 2013: Due to a production error, Exxon Mobil was misspelled. (Return.)