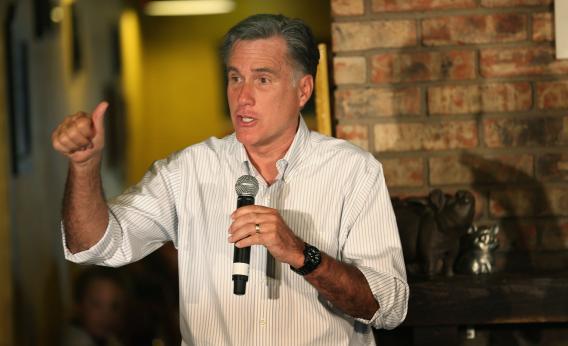

Whatever else happens in American politics, Republicans have one big advantage: They favor low taxes, and people really don’t want to pay more taxes. For the past five years, Democrats have countered this by reassuring voters that their plan is to have someone else pay higher taxes. But it’s difficult to make this work mathematically and difficult for Democrats to persuade voters that they really mean it. Yet a bombshell report released last week by the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center shows that Mitt Romney has given Democrats the greatest gift they could hope for—a Republican plan for a broad increase in middle-class taxes.

What went wrong?

A core conviction of the Republican Party since the election of Ronald Reagan is that lower taxes on high-income individuals is the key to economic growth. This belief has grown especially rigid since the Gipper’s departure from the scene. Reagan himself had sufficient credibility with conservatives to cut deals with Democrats on taxes as well as other issues. But George H.W. Bush’s decision to sign a budget that raised taxes as the price for getting Democrats to agree to spending cuts was widely denounced as heresy. Following H.W.’s defeat, Bob Dole, George W. Bush, John McCain, and all the 2012 contenders have run on platforms of tax cuts for the rich—an agenda that’s been equally pushed by Republican congressional leaders.

The price of this policy has typically been large budget deficits. That’s because even though conservatives espouse spending cuts and sometimes even vote for them, they have little interest in letting their tax agenda be held hostage to the difficult political lift of major spending reductions.

“Reagan proved deficits don’t matter” was the watchword of George W. Bush-era economic policy. And in political terms, it worked great. Rather than yoking tax cuts for the rich to unpopular, offsetting cutbacks in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, they were yoked to a smaller but still meaningful—and politically appealing— reduction in middle-class tax rates.

But then came the great crash of 2008, the inauguration of President Obama, and the 2009 stimulus bill. Ever since, Republicans have embraced the rhetoric of debt reduction with the fervor of converts. High deficits is the aspect of Obama-era economic policy that has the most in common with the policies the past two generations of Republicans have espoused, but the current generation has assailed Obama for it with a breathtaking level of hypocrisy. Then along comes Romney, ever eager to mold himself to whatever is the current fashion in conservatism. How could he enact growth-enhancing reductions in the marginal tax rates paid by high-income individuals without piling on hundreds of billions in new debt?

His plan is simple: Close loopholes and lower rates. “By virtue of doing that,” he told campaign donors, “we’ll get the same tax revenue, but we’ll have lower rates.”

It sounds almost too good to be true and, indeed, the Romney campaign has offered few details of exactly what deductions he would eliminate in order to finance his very detailed program of reductions in tax rates. The only specifics he has provided have been about which tax preferences he won’t get rid of—the ones that offer preferential tax treatment of investment income.

Fortunately for us, the busy beavers at the Tax Policy Center were able to fill in the details. They were interested in the distributional consequences of Romney-style reform, and they reasoned that the best way to enact it would be to establish a best-case scenario for the middle class. Look at all the tax breaks that are on the table, in other words, and start by eliminating the one that’s most favorable to the wealthy. Then take away the second-most-favorable one. Repeat until you’ve done away with enough tax breaks to pay for Romney’s tax cuts. Then run the numbers and see the consequences. What you get turns out to be a substantial decrease in the after-tax incomes of households with less than $200,000 a year in income, to the tune of 1.2 percent of total income on average. Richer households, by contrast, will pay less in taxes than they do now.

The issue here isn’t so much that the tax breaks Romney would have to close are such great deals for average people. Even things like the home mortgage interest deduction that are frequently touted as middle-class benefits do more to help rich people, who own fancier houses. Indeed, if Romney were to try to pay for these tax cuts through reduced spending, the results would be even more regressive. It’s just that the kind of broad tax cuts Romney is proposing are very favorable to high-income families, meaning basically that any way of paying for them would shift income up the ladder. At the moment, the Romney camp is responding to the analysis with sputtering indignation, denouncing it as a “biased study from a former Obama staffer” in reference to co-author Adam Looney’s previous experience as a staff economist on the Obama administration’s Council of Economic Advisers. These staff roles, however, are not political positions (a young Paul Krugman was a Council of Economic Advisers staff economist during the Reagan administration), and the Tax Policy Center’s director, Donald Marron, was an actual political appointee to George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers.

If Romney wants to cut taxes on the rich without hurting middle-class pocketbooks, he needs to return to the faith of his GOP forefathers and ask, “What would George W. Bush do?” The answer is simply not to pay for the tax cuts. That would mean admitting that the attacks on Obama-era deficits are bogus. But it would also have the virtue of being true. For all that Democrats mewled about deficits during the Bush years, there’s precious little evidence they did the economy any harm. Right now the government can borrow money basically for free, so there’s little reason to pay for anything. That wouldn’t be my ideal economic stimulus plan, but it’s better than doing nothing and certainly better than the middle-class tax hike Romney has backed himself into proposing. But the first step toward improving his proposal would be admitting he has a problem.