Maureen Schilling tends bar at Bentley’s Place, a beaten-up tavern at the corner of Somerset Street and Kensington Avenue in Philadelphia. She’s worked there 27 years, at one of the most notoriously drug-ridden corners of the city, with just a quick hiatus to play a bartender on screen.

“I was No. 17 on the credits, I counted them,” says Schilling, who appears in 2006’s Rocky Balboa for about 11 seconds, beginning at the 2:48 mark. She can reel off facts and nicknames about all the other extras in an alternate bar scene that never made the final cut of the movie—“There’s One-Eye Richie, there’s Betty Anne’s-ex!”—which was filmed inside a neighboring, now-defunct shot-and-beer bar.

Schilling hasn’t seen director Ryan Coogler’s new Rocky sequel Creed, but she’s still enthused by it. The movie opened strong nationally last Wednesday and performed exceptionally well in the Philadelphia region—hardly a surprise, since there’s no character in the seven Rocky films that has more personality than the city itself. “They’re talking Oscar this time, for Stallone’s acting,” she says. “He likes to run through the city, that man. And he makes Philadelphia look great, because the camera goes by so fast.”

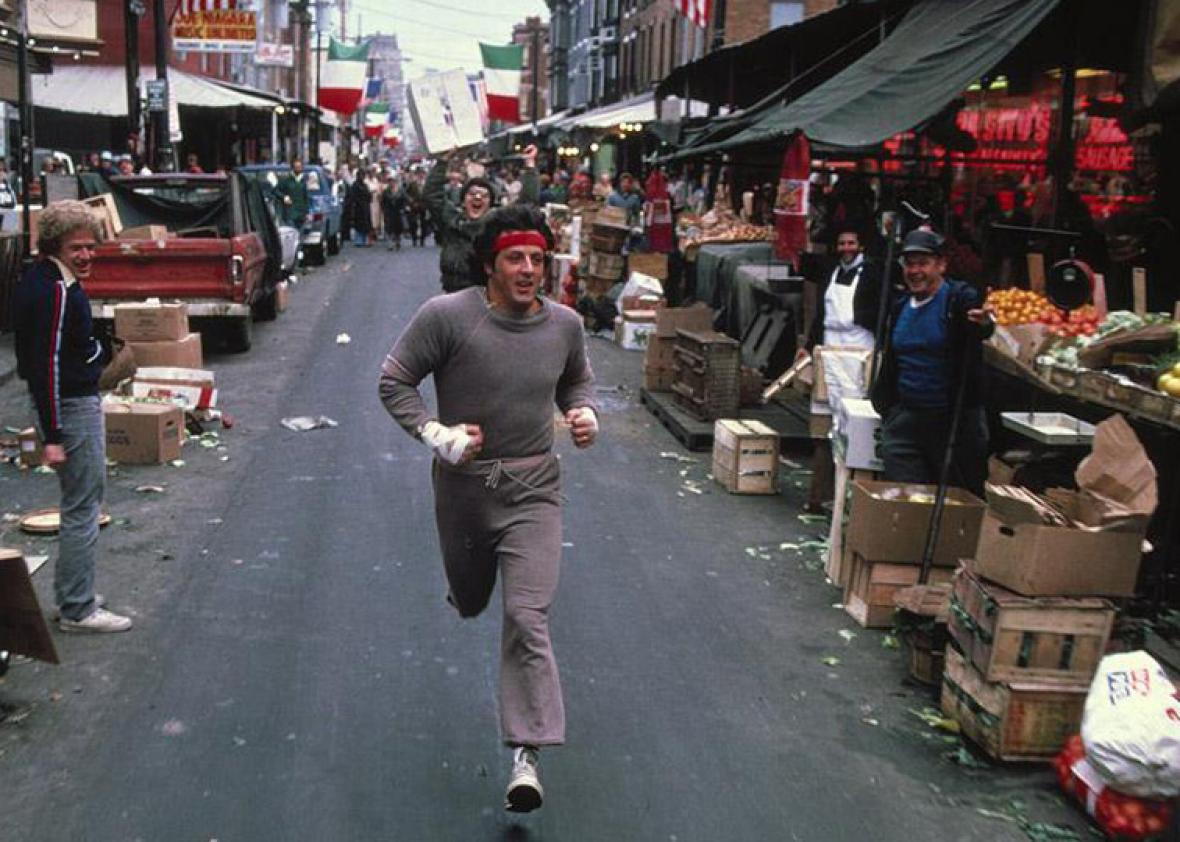

The Rocky franchise, which immortalized Sylvester Stallone’s good-natured, rough-hewn boxer, is famously based in Philadelphia, where the long training montages wend around the city’s sights: the Second Empire majesty of City Hall, the lively confines of the Italian Market, the tourist trappings of Independence Hall, the stately hulk of the Philadelphia Art Museum. The statue of the fictional boxer, located at the base of the museum’s steps, attracts long lines of camera-wielding fans.

But much of day-to-day life depicted in the series, especially and most memorably in the first film, takes place in the deeply depressed blocks surrounding Bentley’s, the area known as Kensington. The trajectory of these communities is just as relevant to the future of Philadelphia as the revitalized downtown that most visitors see or the nimbus of gentrified neighborhoods that attract most middle-income new arrivals. Creed, in which Rocky Balboa trains the son of his old rival Apollo Creed, acknowledges the revitalization of Philadelphia’s Center City when its cameras linger on the phalanx of skyscrapers now visible from the Philadelphia Art Museum steps; when Rocky first climbed them in 1976, only City Hall and a few boxy office buildings could be seen. But just as the first movie did, Coogler’s film sets much of the action in impoverished, outlying neighborhoods, continuing the series’ tradition of depicting working-class and poor neighborhoods without romanticizing their inhabitants nor reveling in the gruesome dictates of the underground economy.

Photo via United Artists

Scenery alone doesn’t explain the appeal of the Rocky movies to Philadelphians, whose underdog stories match the narrative of a city that never quite collapsed into full-blown urban crisis, but which also hasn’t seen the enormous infusions of capital that have rapidly upscaled other cities in the Northeast. Philadelphians like to see themselves as resilient survivors whose story is reflected by the indefatigable boxer. But the Rocky films reflect their milieu in more specific ways. The problems facing the long-deindustrialized neighborhood that Rocky has been jogging around for close to 40 years are as intractable as ever, while other outlying areas of the city that once contributed mightily to the local tax base are becoming poorer as reasonably paying working-class jobs continue to vanish. Rocky may be back, but his neighborhood and city are still bruised. And the films have never shied from showing their struggles.

In the first Rocky film, the Italian Stallion lives in a one-room apartment in a two-story brick rowhouse in Kensington that seems to be carved into numerous units. The surrounding neighborhood comprises more of the same, although no vacant lots or homes are visible. It’s studded with small businesses and large-scale industrial concerns like shipyards and the meat-packing plant where Rocky’s best friend Paulie works.

So what was Rocky’s neighborhood really like? Looking at the census tract that contains much of the action from the first film, the 1970 census shows a neighborhood of 11,210 that is 99.2 percent white, with an unemployment rate of 6.2 percent, and an average family income of $54,996.97 in today’s dollars. The neighborhood appears to be relatively stable, although it’s definitely showing signs of decline in the 1976 film. Nonetheless, almost everyone is employed, and Rocky is the only notable character working in the underground economy (as a reluctant enforcer for a loan shark).

A closer look at the census numbers shows a labor-force participation rate of only 39.7 percent in 1970. Once Kensington manufactured everything from processed steel to magazines to sleds and Stetson hats, while Kensington Avenue bustled with shoppers. But newspaper headlines of the mid–1970s show that many of the manufacturing jobs stitching the community together had largely already been destroyed before the Reagan Recession, when mass industrial layoffs drove up unemployment to levels unseen since the 1930s. A Philadelphia Inquirer article from 1977 reports that Kensington and its neighbors had suffered 84 percent of Philadelphia’s manufacturing job losses thus far that decade. The most fantastical part of 2006’s Rocky Balboa wasn’t Stallone’s character getting back in the ring, but that Paulie still had a job in the same factory 30 years later.

The same 1977 Inquirer article frets that Kensington and its industrial neighbors are “sliding downhill faster than the worst ghettos in town.” Today that prognostication has been proved devastatingly accurate. Vacant houses and lots pockmark the neighborhood; there are even a couple of gaping lots and one boarded-up house on the stubby end of Tusculum Street, where Rocky lived in the first film. The bars featured in the first Rocky film have been closed and demolished, which is why Stallone used the exterior of Bentley’s as a stand-in in Rocky Balboa.

The weekend after Creed’s opening, Bentley’s was almost empty, even though it was Sunday evening and a football game was playing above the bar. Beneath the elevated train stop, a few cops stood guard over what once could be called one of the hottest drug corners in Philadelphia. (It still claimed the title as of 2011.) “It’s better than going to the movies, being up here, and cheaper too,” says Schilling. “Lots of excitement around here in the summertime. Thank God for the winter. Everyone goes inside and it gets quiet out. Well, kind of quiet.”

The action has visibly moved just up the street. A block to the west on Somerset, away from the police sentries, a couple of craggy older women chant “works” (meaning clean needles are for sale) at passersby. The corners are thick with young men—black, white, and Latino—hawking “red tops,” “premium dope,” and “knock out.” The block where Adrian and Paulie live in the first film, Rosehill Street, sits amid this active, open-air drug market. The dwelling attached to their place, which includes a rare patch of front yard, is vacant, and overgrown weeds have colonized the lawn where Rocky once came courting. A couple sitting on the porch of the house next door say they’ve never seen anyone else come up the block looking for Rocky-related landmarks.

Today the same census tract that includes Bentley’s and the house where Adrian lived—and which abuts the tract containing Rocky’s apartment—only has 6,171 people, with a labor-force participation rate of 14 percent, 32.4 percent unemployment, and a median household income of $15,392. The child poverty rate is 84.1 percent. The racial demographics, meanwhile, are now less than a quarter each of white and black residents, with a majority Puerto Rican population.

“The neighborhood has changed three or four times over since the first movie,” says Schilling, who lives to the south in the more stable, white working-class neighborhood of Fishtown, which is now one of the hottest residential markets in the city. “[Bentley’s] used to be packed day and night, now it gets a little busy on weekend nights but not like it used to be. When I was young there was a bar on every corner. Barber shop, shoe shops, corner stores. Not anymore.” To the south of Bentley’s, the pet shop where Adrian worked in the first Rocky is now vacant and surrounded by empty storefronts and weedy lots.

Areas like Kensington, where the Rocky story began and periodically returned, are often left out of the narrative of revitalization that Philadelphia’s leaders try to project outward these days. Along with their neighbors to the west, stretching across North Philadelphia, they are the locus of the local drug trade and, relatedly, where many of the city’s murders take place. Besides the occasional film enthusiast, they don’t attract tourists; the Pope and his entourage didn’t stop there when they visited Philly in September, nor, no doubt, will many attendees of the Democratic National Convention this summer. Commuters mostly don’t make it this far either, not counting police officers and social workers. That neighborhoods with such excellent access to mass transit remain so depressed serves as a reminder that Philadelphia’s future won’t necessarily resemble New York, Boston, or Washington D.C., whose issues of vacancy, violent crime, and deep poverty have been allayed—although not eradicated—by capital flooding back into the cities.

Kensington and its struggling neighbors are the most extreme and intractable manifestations of the poverty that tears at America’s fifth most populous city. But even as Center City–adjacent neighborhoods are rejuvenated, many once-stable working-class communities on the periphery of Philadelphia are seeing their median incomes drop while poverty and crime increase. Meanwhile, neighborhoods like Tacony and Mayfair, where the Great Recession wiped out many lower-middle-class jobs in the private sector, don’t have it nearly as bad as Rocky’s old haunts, but they still suffer from declining incomes and worsening poverty. Interview a resident of the lower Northeast, long one of the city’s most stable postwar areas, and you’ll encounter fears that the area could become the next Kensington.

Like the Rocky films before it, Creed seems to understand its city; while it acknowledges that parts of Philadelphia are bouncing back, it doesn’t forget that other parts of town are still a world apart. Those towering skyscrapers serve as a mute testament to a city that is seeing its population grow for the first time since the 1950s, but Coogler rightly spends most of his time in the outlying neighborhoods. He even includes a stunning tribute to the dirt-bike culture that grips many impoverished young city dwellers in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and other large American cities.

The Rocky movies, including Creed, hold such an allure in part because they don’t ignore or try to pathologize areas like Kensington and their residents, most of whom are simply struggling to survive in a community deprived of resources. Alongside the grotesquery of the drug markets around Kensington and Somerset, there are still rowhouses decked out for Christmas or guarded by pumpkins dressed up as Thanksgiving turkeys. From the elevated stop, you can spy the interior of a tidy upper-story apartment, and hear the hiss of a tea kettle. Rocky’s old training grounds, and much of Philadelphia, are still struggling. But they aren’t quitting either.